The Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo is now the second largest in history, according to figures from the World Health Organization. Since the outbreak was declared Aug. 1, 426 people are suspected or confirmed to have been infected with the deadly hemorrhagic virus, which has killed at least 242.

“It’s a tragedy because it should be completely preventable, but it’s not,” J. Stephen Morrison told HuffPost. The director of the Global Health Policy Center, a program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, stressed that, although this outbreak still pales in comparison to the one that began in 2014 in West Africa ― killing over 11,300 and infecting 28,600 ― it is highly dangerous.

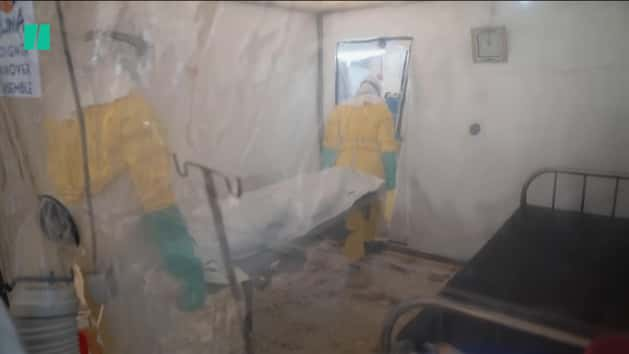

The Ebola crisis has become a battle with many fronts. The outbreak is in a war zone, where violence and protests often interrupt the efforts to control the disease. There has been an uptick in community resistance to the medical operations, which are often staffed by international responders whose outsider status sometimes elicits fear and distrust, especially in the newest hotspots of the outbreak in Butembo and Katwa. The lead-up to the country’s elections on Dec. 23 are expected to be fraught with even more unrest and political instability. And now there’s a threat of terrorism directed at the U.S. Embassy in Kinshasa, which might limit an already-restricted flow of U.S. responders to the DRC, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Case counts continue to climb, health workers continue to make up nearly a tenth of the cases, and infants and children continue to get infected at alarmingly high rates.

The WHO’s assistant director-general for emergency preparedness and response, Mike Ryan, stressed that, although the international organization knows its strategy will work, there is no “magic bullet” to extinguishing the outbreak other than grinding out a response.

“We’ve just been striking behind the virus almost all the time” during this outbreak, he said. “The virus gets out to the next place before we have a complete chance to shut down transmission.”

“As long as it’s getting worse, not better, the end is really not in sight.”

- Ron Klain, former Ebola czar under President Obama

Morrison and other global health experts are particularly perturbed that the outbreak in the northeastern region of the DRC has grown to this size considering the significant new tools ― an experimental but highly effective vaccine and new therapeutics ― now in the arsenal of global health. More than 30,000 people have been vaccinated to stop the spread of the disease ― a response that could only be deployed at the tail end of the West Africa outbreak in 2016 ― and yet the DRC outbreak continues to grow.

“We’ve hit this point where we have all the tools to arrest this outbreak, but that effort is not succeeding, and we have to ask ourselves why,” Morrison said.

With the rising case numbers, experts worry about the possibility that Dr. Robert Redfield, head of the CDC, raised earlier this month: that Ebola could become “endemic” for the first time in history — meaning it would not be stomped out and would live on in the region.

“The human toll is mounting, and the risk of spread to Uganda is rising, and on its current course, this epidemic is getting worse, not better,” Ron Klain, the Ebola “czar” in the Obama administration, told HuffPost. “This is the paradigm of the truly frightening epidemic problem of the future, where it isn’t just about how hard it is to control with regards to medical issues but with the security, diplomatic and geopolitical issues.”

A Cascade Of Problems

According to WHO’s Ryan, the situation at the epicenter in the city of Beni appears to be moving in the right direction. But the ongoing violence is a constant concern ― which led to the case counts doubling in October ― and there are two new hotspots in Katwa and Butembo.

An uptick of cases in Butembo, which is a sprawling community of 1 million people with limited infrastructure located less than 30 miles from Beni, raises the risk of rampant urban spread. Médecins Sans Frontières is considering opening another Ebola treatment unit in the area, as Ryan said the current one is almost at capacity.

And community resistance continues to be a major problem as the outbreak creeps into new areas, like Katwa. Last weekend, local residents retrieved the highly infectious body of an Ebola victim from a Katwa health center instead of allowing the staff to safely bury him, Nora Love of the International Rescue Committee told HuffPost. As Love, IRC’s emergency field coordinator in Beni, noted, as the outbreak spreads, new communities have to become informed about the risks of spreading Ebola while they learn to trust the arriving medical teams.

This community resistance has sparked the most concerning trend over the last few weeks in Katwa and Butembo: A number of people who had come into contact with known Ebola patients refused vaccination or follow-up and were found days later in health facilities or dead in their homes after they had likely further spread the disease.

“Many were known as contacts but had disappeared from follow-up because they don’t want to be found,” Ryan said. “That’s a worrying trend as that means to some extent the disease is underground.”

And that’s to say nothing about the growing dread over elections set for Dec. 23. The elections for President Joseph Kabila’s successor, which have been delayed for two years, are already fraught with community distrust. And the northeastern region where the outbreak is occurring is already very hostile to the national government, Morrison said, due to the lack of security for the last 20 years. So no one is quite sure how the country will react to the election’s results ― no matter which way it goes.

MSF Ebola expert Dr. Michel Van Herp, who was on the ground in October, said the mass crowds, population movement and possible political violence the election could create would only make the outbreak more difficult to control.

For Klain, all of these complicating factors mean this outbreak is far from over.

“As long as it’s getting worse, not better, the end is really not in sight.”

A Hamstrung U.S. Response On The Ground

The U.S. has been criticized during this outbreak as “leading from behind,” in Klain’s words. While the U.S. has donated large sums of money and expertise to the response, the CDC and USAID responders are not allowed to be on the ground at the outbreak’s epicenter due to fears for their security, in what experts are calling a “Benghazi-hangover.” That takes some of the world’s top experts out of the line of potential fire from the violence in Beni, but also out of the Ebola outbreak zone.

The fighting around Beni that prompted the August withdrawal of part of the CDC force back to Kinshasa, the nation’s capital, was primarily instigated by the insurgent group Allied Democratic Forces. ADF has terrorized the region for decades ― killing U.N. peacekeepers and DRC military forces, and targeting civilians in machete attacks and child kidnappings. A report released two weeks ago by the Congo Research Group, based at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University, cited ties between the group and an Islamic State financier, Waleed Ahmed Zein, who had sent an undisclosed amount of money to ADF.

The U.S. Embassy in Kinshasa has been closed to the public since Monday after issuing an alert about a “credible and specific” terror threat over the weekend. CDC spokesperson Benjamin Haynes told HuffPost that in light of the threat and State Department guidance, it is unclear whether new U.S. response personnel would be able to head to the DRC until Feb. 1 at the earliest, meaning the U.S. response in the country may not be able to surge with the rising cases.

While the WHO’s Ryan stressed that he’s thankful for the tremendous U.S. funding and the CDC staff assisting with surge efforts from Geneva and across the DRC borders in neighboring countries, that lack of on-the-ground assistance is a loss.

″It would obviously be a great development if we could see more CDC resources on the ground, but that’s not for lack of effort or heart on the part of CDC,” Ryan said. “Everyone has to take into account the security assessments of their own individual countries.”

On Thursday, in the Journal of the American Medical Association, over two dozen global health leaders called for a surge in CDC workers, not only in Kinshasa but also at the outbreak’s epicenter. They are part of a growing chorus of experts urging the return of the CDC on the ground, arguing that without the agency’s extensive expertise and resources, this outbreak will continue to grow.

A Question Of International Leadership

Klain’s concerns about the U.S. government’s abdication of its leadership role are echoed by many other global health experts, who say that, without an increase in true international willpower, this outbreak will continue to fester and expand.

Morrison was a bit more blunt, saying there was “no appetite” among the U.S., U.K., Germany, France and other global leaders to step up with the resources necessary to truly intervene.

“There’s a certain level of silence about this,” he said. “I just think we’re in a particular moment in time between inward populism, rampant nationalism, Brexit and EU crises and America First that has changed security calculations.”

“We’ve hit this point where we have all the tools to arrest this outbreak, but that effort is not succeeding, and we have to ask ourselves why.”

- J. Stephen Morrison, head of the Global Health Policy Center at CSIS

Dr. Thomas Inglesby, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, argued in an article published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine that the WHO needed to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. The WHO elected not to call a PHEIC for this outbreak earlier last month.

“The WHO, DRC, other governments, including the U.S., and NGOs need to identify ways to intensify efforts beyond what has been possible to date,” Inglesby told HuffPost. “If the effort isn’t intensified, the outbreak is likely to worsen.”

Or, as the authors of the JAMA article put it: “It is in the U.S. national interest to control outbreaks before they escalate into a crisis. The cost of addressing this epidemic now is far less than if mass mobilization were required due to international spread of the virus.”

Amidst this debate, the WHO and volunteer non-governmental organizations are still working on the ground. Many people have been deployed multiple times over the course of the year, since the WHO and NGO staffs, alongside DRC’s Ministry of Health, have essentially been fighting Ebola in the DRC since April, when the Equateur outbreak was declared. That outbreak ended just a few days before this one was announced.

“Everyone has been working for a long time, everyone is tired, everyone is stressed and now is the time we have to double down,” Ryan said. “We have to not just sustain our effort, but we have to increase our effort in the face of fatigue and insecurity.”

The Dreaded Worst-Case Scenario

Global experts fear a worst-case scenario in which the ADF or Mai Mai, another rebel group, attacks or kidnaps Ebola health responders (kidnappings of NGO workers and clergy in the area have happened for years). That would trigger a complete pull-out of the international response team, which Morrison fears is “fairly close” to happening ― and would be “catastrophic.”

“The spread has been slowed and contained up to a point by the international mobilizations, but it’s not working in terms of arresting it and bending the curve,” he explained. “It’s slowing the trajectory. If you take those binds away, there will be a rush and an acceleration.”

Ryan spoke of the grave possibility as well.

“We just hope right now that the security system doesn’t deteriorate any further, which might trigger a necessary pullout of the field, and nobody wants that. Because at this point, if we have to pull significant resources back out of the field, this virus just runs out of control.”