A Conversation with Alan & Marilyn Bergman

Mike Ragogna: Have I got Alan?

AB: You've got Alan and you'll have Marilyn in a second

MR: How are you, by the way?

AB: Very good how are you?

MR: I'm very well, thank you. I've been looking very forward to this interview, and...

Marilyn Bergman: ...here I am!

MR: Hey there, nice to meet you, Marilyn.

MB: Thank you!

MR: Okay, let's start with a question many people are probably wondering about, which is when did Alan and Marilyn Bergman become such an establishment in the world of music?

MB: [laugh] I never knew we were an establishment! I don't think I can answer that question.

MR: [laughs] Right on. Partners, that's it. No establishment...partners.

AB: Ah, a long time ago. Fifty-seven years ago. Well, actually, I think it's been longer.

MB: How can that be when I'm only sixty?

MR: [laughs] No denying, you added a lot to pop culture with songs like, "What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life?" and "Windmills Of Your Mind" with Michel Legrand, "It Might Be You" with Dave Grusin. What is it that makes your musical partnership a successful one?

MB: Our partnership as writers or as husband and wife? I think the aspects of both are the same: Respect, trust, all of that is necessary in a writing partnership or a business partnership or in a marriage.

AB: In addition to what Marilyn said, we love each other and we love to write songs and that combination is paradise.

MB: We like to have the music first. Sometimes the composers like us to give them a line or two or a rough draft of a lyric, But we really much prefer to have the music first. So to reframe your question, I think what could happen first thing in the morning is one

of us will wake up and say, "I have a good idea." That's always nice to wake up hearing.

MR: [laughs] Beautiful. I'm imagining you write often enough that you know a gem when you've written it.

MB: There are some things that you feel have something special about them, or they meet the assignment in a particularly fortuitous way. If something sounds like it's just another song, the last thing the world needs is just another song.

AB: And usually when someone asks that question, what they are asking is if we know if it's going to be a hit.

MB: Is that what you're implying?

MR: Yeah, I just meant merely a gem. [laughs]

AB: A gem for us would be a great melody and hopefully, lyrics that do it justice.

MB: What you don't know is if something is going to speak to people over time. I think that's the acid test. With anything.

MR: Okay, but what about when you were creating something like, "What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life?" from the movie The Happy Ending. That's such a classic...

MB: Things only become classics over time. There's no such thing as an instant classic.

I don't think.

MR: True, but there are some people who say, when they were writing a certain song, they went, "Oh my God, yeah, this is THE thing." Do you have any of those songs that popped out like, "We've got to run to whomever with this song?"

AB: No, we'll put it aside and look at it the next day to see if we can make it better.

MB: Those three songs that you mentioned were all written for movies. "Windmills," "What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your LIfe" and "It Might Be You." In the case of "What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life?", the director Richard Brooks gave us a very specific assignment. The song was to be heard twice in the movie. We couldn't change a note or a word, but it had to mean something entirely different the second time.

AB: The first time it is behind a love montage. The second time is sixteen years later; they've married. The wife is an alcoholic who leaves her husband and her daughter never to go back home again. She goes into a bar, orders several martinis, puts a coin in the jukebox and we hear by the very same singer, the very same song. Now that's a great assignment! We knew it when we got it. "Wow, that's interesting"

MR: What inspires you lyrically?

MB: We had that whole film as inspiration.

MR: But you had to really delve deeply into the characters as well as the film itself,

right?

AB: We try to. That's the function of the song. We had great directors like Richard Brooks, Sydney Pollack and Norman Jewison who knew the function of a song and how

it could be an extension of the screenplay. And when Michel Legrand played us that

beautiful melody, we knew there were words on the tips of those notes and we had to

find them.

MR: There you go. That's a beautiful way of saying it. So you have all of these deep, emotional songs, and on the other side you have "It Might Be You," where we knew as much about Tootsie from that song as we knew from Dustin Hoffman's performance. Is it just that you guys are good?

AB: [laughs]

MB: Good's not good enough. You know that.

MR: I'm just wondering how you guys are able to do these reads that are so exact. Do you think it's because you're students of human nature and might know a thing or two about people in general?

MB: We were both musicians first, so that's a start. I know it's true of Alan and of me, and from a very early age, we loved songs and loved movies. I remember the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movies and those songs by the Gershwins and Cole Porter. I had Fred Astaire's picture up on my wall, he was a pin-up boy for me. I'm talking about when I was eight or nine years old maybe. He told stories. He sang very simply but he really told a story with every song.

AB: Those were wonderful songs. That's the music that I remember from my childhood. So that may have set a level of what a song should accomplish, particularly a song from a movie. Now if you look at the end credits of a movie, they credit fifty songs and you think, "I don't remember hearing all of those," and then if you watch the picture again,

you'll say, "Yeah, there was a three-minute snippet of something there."

MR: Marilyn, I interviewed Paul Williams a while back, and one thing you have in common with him is that you both were chairman and president of ASCAP. I remember that because I'm an ASCAP member and I used to get your signature on mailings all the time. During those years when you were the President of ASCAP, a lot of interesting things happened.

MB: That was probably the most challenging part of those years. During the birth of the internet. The difficulty of protecting music and songs. That changed the whole

business. Totally changed it.

MR: Essentially, we went from buying a physical product to buying a virtual product.

MB: In a way, I suppose so.

MR: Alan, you've made a CD. Singing. Can I get a couple thoughts on your album Lyrically, Alan Bergman?

AB: Oh, I had a wonderful time doing that, and I'm going to do another one.

MR: The music industry is so fragmented right now, could an Alan & Marilyn Bergman surface in this era?

MB: Oh, I don't know. The directors are different. Sydney Pollack for example...Sydney Pollack was a student of both music and of songs and he didn't just want to use a song just to decorate a film, he knew exactly what he wanted a song to accomplish and was very specific.

AB: The point is what inspires us is the film.

MB: I don't think directors view the use of music the same way they used to.

MR: I guess what I'm also asking is could a powerful film songwriting couple who uses depth and emotion and humanity the way you do happen again?

AB: I don't know. A lot of it has to do with the directors. They'd talk about trying to become an extension of the screenplay, part of the fabric of the movie--people like Sydney Pollack and Norman Jewison knew how a song could enhance a scene or illuminate a character.

MR: I want to jump in because I remember a scene from Up The Sandbox...

AB: [laughs] ...you're sitting by your computer!

MR: No, really, I'm old enough to remember it. I had the Barbra Streisand album with "A Child Is Born." I really, really loved the song. I know, it was never in the movie

but...

MB: It's amazing that you remember that song!

MR: But while we're on that subject, how did your association with Barbra Streisand first start?

MB: Oh, I feel like I've known her all of my life! When did we meet?

AB: She was eighteen or nineteen years old...

MR: She's recorded a great many songs of yours.

AB: Maybe sixty-four songs of ours. It's thrilling every time. She's a great singer and also a great actress and director.

MR: And to this day, I believe she represents someone who's carrying the flag for a depth in songwriting.

AB: No question.

MR: I mean, look at the songs in Yentl...

MB: I do look at them, Mike!

MR: [laughs] That was you guys, but I'm just saying. Can you remember the experience of putting that project together with her?

AB: We had so much fun.

MB: Oh, it was great. We had Michel to write with and Barbra to write for, what's better than that?

AB: And a wonderful story! She did a phenomenal job as a director.

MB: Extraordinary!

MR: [sings] "And then there's Maude."

AB: Well that's a great piece of film, too! Norman Lear said, "I want you to write an entrance for Bea Arthur's character.

MR: Of course, everybody remembers the hook, but my favorite part is right before the break [hums part]. Who came up with that again?

AB: Musically, that's Dave Grusin.

MR: You guys were honored by the Johnny Mercer Foundation, too. What was that

like?

AB: He was my mentor and I spent two or three years with him. He would listen to what I was writing and encourage me over a period of maybe three years. He was wonderful to me. I can't say enough about him, and for us to get something in his name is really

important.

MB: If you wanted to name great lyric writers, John is probably right up at the top.

AB: And he was the most versatile. He could write anything.

MR: ...there's so much, and of course, there's "Moon River." Did you ever see him in action writing anything?

AB: Not writing, no.

MB: That's very private.

AB: But I'm one of the few lyric writers who has two songs where I wrote the music and John wrote the lyrics!

MR: Beautiful.

MB: Alan and John were very close friends beyond the fact that he was Alan's mentor and in this case a collaborator!

AB: It was a dream come true because as a kid in Brooklyn, the first piece of sheet music I ever bought was a song called "Lost," which John was one of the writers on. I was maybe eleven or twelve years old.

MB: So to get an award in his name was very meaningful to the both of us.

MR: By the way, it would be wrong to leave out that you co-wrote "You Don't Bring Me Flowers." Were you surprised by how big a record that thing was?

AB: Oh, sure. That became a big record because of a disc jockey in Kentucky who was having trouble with his wife. Neil had recorded it and Barbara had recorded it separately and he put the two together.

MB: He made the duet on a tape and he played it on his show one night and the phone lines just went crazy. People wanted to know where they could buy that record, but there was no such record! Columbia Records didn't let that slip by. They saw to it that

Barbra and Neil recorded the duet.

MR: That's such a wonderful thing, and I think the phrase, "You don't bring me flowers" has since become something of a euphemism.

AB: Has it really?

MR: Are there any projects you're currently working on?

AB: Yes, we're working on many things. One is a score for an animated movie that we're writing with Dave Grusin. And we are writing new songs for a new production of "Ballroom" to be mounted in London next year.

MR: Considering the incredible careers you've had, what advice do you have for new artists?

MB: Do you mean writers or singers?

MR: If you want to cover both, that's cool.

AB: Well, for one thing I would say know the literature of popular music. Go back and listen to the great songs. There's a reason why songs like Irving Berlin's are still played and sung. Especially listen to Stephen Sondheim.

MB: For writing for the theater.

AB: For writing anything.

MB: That's true.

AB: He wrote two books that are really primers for people who want to write. They're wonderful books. And listen to all those great writers: Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, the Gershwins, Lerner & Loewe, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Rodgers & Hart, those are the people who have written songs that you call "gems"!

MB: One talks to aspiring filmmakers and they can tell you every frame of a classic movie that goes back before they were born. They know Eisenstein's films as well as early Frank Capra and Hitchcock and Orson Welles. Those are like the classic songs that we studied, right? If you talk to architects, they know every famous building.

AB: Going back to The Forum!

MB: But I don't know that aspiring or sometimes even very successful songwriters know what came before them!

MR: That's a very good point. It's not emphasized. Maybe there's a confusion because there has always traditionally been a separation, when teaching music, between classical or jazz and then teaching what would be popular music. I think popular music always gets the raw end on that deal.

MB: If one really is serious about wanting to write songs that are original, that really speak to people, you have to feel like you created something that wasn't there before--which is the ultimate accomplishment, isn't it? And to make something that wasn't there before, you have to know what came before you.

MR: I think so too. You have to have a foundation.

MB: I would think!

MR: And a language. A language everyone can speak before having "the conversation."

AB: And there's a rich literature of this music.

MR: Do you think that that's something that's correctable within the educational system?

MB: Sure. Sure it is.

MR: Well, then again, with a lot of school funding going away, the first thing that gets slashed is music.

MB: The arts in general. Yes, we're probably fast approaching the time where there's a whole generation of young people who won't know who Mozart was. The name will be totally unfamiliar.

AB: Yeah, when you realize that in New York there's one classical music station...

MB: ...one classical music station in a city that size! It used to have three or four.

AB: You go now to the concerts at the LA Phil, they have a great conductor, but you walk in and you're looking at a sea of grey hair.

MR: [laughs] But on the other hand, The ASCAP Film Scoring and Television workshop has its twenty-fifth anniversary this year. One of the exercises was everyone was given a film clip and they each had to come up with a composition for it. You participated in

this at one point, didn't you?

MB: I did!

MR: [laughs] That's right, wow. Well, so many people were part of it--Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein, all of these people. So you saw, even back then, the need to mentor?

MB: Well, it was a way of teaching, I guess.

MR: So what do you think is the future for those who are serious about wanting to compose for film? What other things can they do to get better other than study the greats? Any advice for new young film-composing artists?

MB: You have to seek out the young directors who understand the use of music in film because ultimately, it's the director who's the boss. There are fortunately quite a few young directors who really do understand music in film. That's the first thing.

MR: Have you been keeping an eye on anybody, saying, "Yeah, that kid's going to do something in another couple of years"?

MB: There are very talented young film scorers. For example. there's a young guy named Brian Byrne from Ireland who's extremely gifted. He knows the soil from whence he came, and it's not that he's imitating or that it sounds in any way like them but he's

built upon the foundation.

AB: He has a sense of history.

MB: And a sense of drama and what contribution music is supposed to make to a movie.

MR: Have you mentored any artists?

MB: No matter what the field, how do you know that you're not rewriting something that was written before you were born? And maybe written much better.

MR: All right, that's beautiful advice. You know, I've had you for almost an hour!

MB: And we have to go back to work!

MR: But I have one obvious question, which is beyond those projects you mentioned. "What are you guys doing the rest of your lives?"

MB: Writing songs.

AB: Having fun, we love to do that. Enjoying our granddaughter and daughter, of course, and life itself. I play tennis every day. I come home at nine-thirty every morning and bring Marilyn her breakfast.

MB: Yes he does, he brings me breakfast, fresh from the tennis court!

AB: And then we listen to music and write songs. How bad is that? Nothing's better than

that.

MR: Beautiful. So the last image I have of you is the two of you cuddling on a sofa listening to some great music.

AB: [laughs]

MB: I don't know about cuddling on the sofa while we're writing...

MR: By the way, I'm friends with Rupert Holmes, I know you know him.

AB: Oh, yes. We brought Barbra Streisand one of his albums and then he did an album

with her.

MR: Lazy Afternoon.

MB: Gorgeous album. The first time we heard that arrangement and the first time we heard a song that he wrote and a book that he wrote we knew just how multi-talented he was. And he's fast! He writes very fast..

MR: He taught me a really great lesson. We were sitting at dinner together and I said, "What did you think it was that turned the corner on you being so in demand and loved to this degree?" He said somebody taught him if somebody asks, "Hey Rupert, can you...?" before they can finish the sentence, you nod your head and go, "Yeeeeees."

AB: [laughs]

MR: And that's how I believe he's become so successful. He's also one of my favorite people, he's a sweetheart.

MB: He's a wonderful guy. Please give him our best if you talk to him soon.

MR: Absolutely! Thank you again.

MB: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

AB: Thank you.

MR: All the best.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

ANGELS SING WITH WILLIE NELSON, HARRY CONNICK JR., LYLE LOVETT, KRIS KRISTOFFERSON AND MORE

About the video...

The cast of Angels Sing talks about making the movie, their characters, and share select scenes from the project that features Harry Connick Jr, Willie Nelson, Connie Britton, Lyle Lovett and Kris Kristofferson. Including "Amazing Grace" by Willie Nelson, "When I'm Home" by Harry Connick Jr & Willie Nelson, and "Christmas Time is Here" by Lyle Lovett, the cast contributed to the soundtrack, all songs listed below.

Get more info on the film at this url http://www.angelssingmovie.com

Tracks:

Up On The House Top - Black Soot

Mistletoe on Death Row - Dale Watson

Deck The Halls - The Trishas

Christmas Time Is Here - Lyle Lovett & Kat Edmonson, with Mitch Watkins

Family Bible - Willie Nelson, with Bobbie Nelson

Signals In The Dark - Sahara Smith

Moses - The Trishas

Christmas Time in Texas - Dale Watson

Christmas Love - Miss Lavelle with Guy Forsyth & Carolyn Wonderland

Silent Night - Carolyn Wonderland & Guy Forsyth

Amazing Grace - Willie Nelson with Bobbie Nelson

When I'm Home - Harry Connick Jr & Willie Nelson

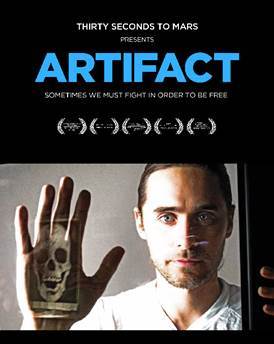

A Conversation with Thirty Seconds To Mars' Jared Leto

Mike Ragogna: Hey Jared, let's jump right into Artifact, because that debuted recently on iTunes worldwide. I'm imagining this is one of the most passionate projects you've been involved with because it hit you so personally. It seems like a strange scenario for anyone to be in.

Jared Leto: It was a very strange scenario, one of the strangest scenarios of our entire lives. Thirty Seconds To Mars had a tremendous amount of success with an album called A Beautiful Lie. It sold millions of copies around the world, we finished up a tour and were about to start making a new album when we found out that not only would we never be paid a single penny, but that we were also millions and millions of dollars in debt. We decided to look into it and were shocked by what we found.

MR: What did you find?

JL: We found that there's a very convoluted system at work that makes it very difficult for artists to make a living from their work. It's a system that leaves the corporation in complete domination of the artists, a system that doesn't encourage partnership. It's a system that, in my opinion, is really not ideal and one that we didn't agree with, so we decided to go to war. We decided to fight for our creative lives and we risked everything to do that.

MR: And when you turned in your next album, it couldn't have been a very pleasant experience. How did you get through that period?

JL: All of the people that were responsible for suing us for thirty million dollars left the company, were fired, or lost control of the company. That would be the person who owned EMI...and he ultimately ended up losing control of that company when he defaulted on a loan to Citibank. So in a sense, it was the same shell of a company but completely different players.

MR: Right, it was the Terra Firma investment company that bought EMI.

JL: I think they made some bad decisions, I think they underestimated the business, I think they underestimated many of the people in the record business who do a great job for artists and for labels, I think they underestimated their ability to deal with artists, they assumed that artists are like products and they can move them around on a spreadsheet and make things work. But artists don't belong on spreadsheets, they belong in creative worlds. So this film examines that uneasy relationship between art and commerce. I'm excited for artists and creative people to see the film. I think that they may be surprised to learn how this business can really work.

MR: What's become popular now are 360 deals that signs over to the entertainment entity virtually all sources of income by the artist. Might these 360 deals be a result of years and years of a kind of corporate arrogance?

JL: I wouldn't say that. A corporation has a certain amount of inhumanity. They're designed to be concerned about one thing--the bottom line, and that's great for the corporation, but it's not so great sometimes for the employees or for the partners of the corporation. It's hard to quantify in terms of returns on investments on the creative contribution from an artist or a designer, so ultimately, a lot of creative people get treated probably less than well in that structure. But sometimes, that's not the case. I think that a 360 deal is an attempt for the corporations to make more money. It wouldn't be a bad thing if the corporations happened to be good at doing some of those other things in that 360 area. Unfortunately, a lot of the record companies are not experts at things like merchandise, they're not experts at things like touring, they're not experts at some of the other areas of revenue, so you end up making a deal with these companies who aren't necessarily experienced in the areas that they're looking to take a piece of revenue from. So that becomes a questionable business model. If they were great at it, then that could be a great business model. If they happened to excel in those areas and really help artists to achieve some of their goals, then great. I think we're in a very strange period right now. There isn't really a clear indication of where the business is going still, and this has been a number of years now. People have been experimenting with a lot of different models and it's an interesting year to see some acts doing great and some acts not doing great, even some of the biggest acts in the world.

MR: You've taken a lot into your own hands in order to advance the career of Thirty Seconds To Mars. I normally ask "What advice do you have for new artists," but to that point, what are some of the things that have been successful for you? What are some things that you think an artist can do for themselves?

JL: That's a good question. One of the things that I've learned is to be really entrepreneurial, to not wait for permission, to be proactive. Thirty Seconds To Mars has been a great guinea pig for other businesses that I got involved with as a founder, as a CEO, and that includes technology, e-commerce, VIP ticketing and packages. We're really proactive in those areas. I would encourage other bands to not sign a record deal until you feel like you have to, until you feel like it's the right time. You want to walk into a record company with as much leverage as possible, so I would tell young artists to focus on building community, to focus on building awareness, playing shows, touring, working on their craft, on writing, on performing, being the best that they can be. Don't be desperate for a record deal, that's not going to solve all of your problems. In some cases, it may add to them. You want to be completely clear about what kind of deal you're signing, you want to be clear about why you're signing a record deal, and be clear about your expectations. There are also a lot of things you can do if you're already an established artist, like we do. We get involved and be proactive and cut out the middleman when we can. There are a lot of great platforms. We started one called VyRT, that allows us to broadcast concerts, and instead of commercials and sponsorships, we make an arrangement directly with our audience, we sell individual digital tickets. So we have this online concert venue now where we can broadcast anything and everything and we use it quite a bit. We premiered Artifact through VyRT and it was a great success; we just broadcast our Hollywood Bowl show there and it was a great success. There are other avenues to look for additional sources of revenue rather than the traditional record label model, and I would encourage other artists to explore those.

MR: That's great, practical advice. It's really up to the artist these days since the old school way of doing things is almost gone.

JL: There are no rules, and it's up to artists to break them, if there are any left. We do what we are inspired and motivated to do. For us, community has always been an incredibly important part of Thirty Seconds To Mars. You have to work hard, you have to be tenacious in order to survive these days. We'll see what the future holds, I'm optimistic about it. It's certainly going to be interesting to watch. I'm really proud that Artifact is finally out after five years in the making and we're able to share our story with the world.

MR: I appreciate your time, thank you so much, Jared.

JL: Thank you, I appreciate your time.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne