With the inauguration of Enrique Peña Nieto of the PRI on December 1, Mexico's short history of multi-party rule entered a new chapter, after a dozen years of rule by the center-right PAN came to an end. There will be much soul seeking among the PAN in the coming months, as the party will witness the gradual cementing of its legacy in what is likely to be less than flattering terms. On the positive side, history will remember the party's first president, Vicente Fox, as the man who brought democracy (electoral at least) to a country which had endured seven decades of one-party rule. However, the past 12 years will also be remembered for being a time of missed opportunities, which prevented Mexico from achieving the institutional transformation it needed or the economic growth to overcome the two "lost decades" of the 1980s and 1990s.

High Hopes, Weak Results

The onset of democracy in 2000 laid bare the intrinsic weakness of a presidency, whose strength during the PRI era was masqueraded by a carefully crafted system of corporatism between the party and the country's multitude of interest groups. The PAN never truly attempted to challenge this order, and became even more passive in the face of legislative gridlock and attempts of interest groups to extract (one could almost say extort) even greater private benefits. The result was a presidency which was effectively "crowded out" of effective governance, limiting its policymaking ability to only those areas where it had direct executive control. For example, structural change was all but abandoned after Vicente Fox's failed attempt at fiscal reform in 2002. Subsequently, Felipe Calderón's attempts were either shot down or watered down, mostly due to the PRI's obstructionism, notwithstanding that many of these policies are now being promoted by Peña Nieto and his team.

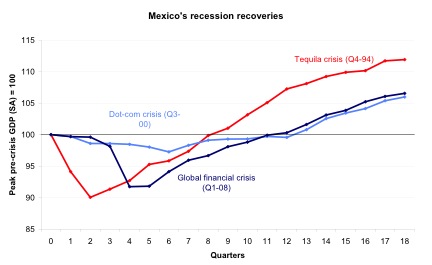

Judging the PAN on its macroeconomic management is easier as it is one of the few areas where it had (mostly) full reign. The numbers speak for themselves and they are hardly anything to gloat over. Between 2001 and 2012, the Mexican economy grew by 2.1 percent per year and just 0.7 percent in per capita terms -- this is the lowest rate of growth of any of the big Latin American economies and lower even than during the crisis-ridden PRI years of 1982-2000. The Mexican economy suffered badly during both U.S. recessions during this period, and recovered more slowly than after the previous ones, both in terms of GDP and employment. Although Mexico's economic rebound in the past two years has been much heralded, the comparisons with the 1994 Tequila crisis are telling. Despite not suffering a financial collapse this time around, it took the economy 12 quarters to recover the peak level of pre-Lehman output whereas it took only nine quarters back then. Despite hitting less hard than either crisis, the fallout from the U.S. dot-com crash during Vicente Fox's term took a staggering 13 quarters to recover lost output!

It would be easy to blame Mexico's historic dependence on the U.S. economy (especially after NAFTA) for the two crises which hit the country on the PAN's watch but that would only serve to absolve the country's authorities from any responsibility, not least for creating false expectations. Vicente Fox promised seven percent growth during his campaign, yet delivered just two percent. In late 2008, then-finance minister Agustin Carstens infamously boasted that Mexico would suffer "only a sniffle" from the global economy's crash, but got both a figurative and literal case of swine flu instead. Felipe Calderón, ran as the "jobs president" and presided over a deterioration of the unemployment rate, which has taken even longer than GDP to recover to pre-Lehman levels. Moreover, Mexico's uncannily low unemployment rate -- even in the worst of times -- masks a much larger problem of underemployment and informality, as well as a gradual deterioration of job quality since the dot-com crisis. This goes a long way in explaining rising frustration from the country's youth, as well as rising crime.

It is here where we have to turn to the one area where the PAN's legacy will suffer its biggest blemish: security. Drug-related violence is hardly new in Mexico, but took a turn for the worst after Calderón launched his "war on drugs" barely a month into his term. At best, the war has been a mixed success in weakening or destroying some of the country's main cartels but, at worst, a colossal failure which has led to 60,000 dead and 25,000 disappeared, leaving its scars across the formerly vibrant border towns as well as industrial centers like Monterrey. Whatever the war's successes, many appear to be less due to government direct actions rather than to the changing fortunes of the cartels themselves, mainly as the two largest of them -- the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Zetas -- have muscled their way into the territories once dominated by their rivals. Ultimately, only time will tell if Calderon's strategy will make the country safer but unfortunately for him, it will be his successors who will reap the benefits.

Looking Towards 2018

Perhaps the harshest judgment on the PAN's 12 years of rule was given by voters in the July 1 elections. On that day, the party that gave Mexico democracy placed a disappointing third as voters castigated a campaign platform which was in no small measure based on repeating the existing formula for another six years (Dilma Rousseff, in Brazil, ran on a similar banner and yet won by a wide margin). This speaks volumes about the level of dissatisfaction with the PAN's two terms in office, and how Fox and Calderon's accomplishments (such as near-universal public healthcare, strict fiscal discipline, doubling of infrastructure spending) failed to make up for their multiple failures and disappointments, plenty of which were not mentioned in this article.

Despite this, the Mexican electorate is anything if not forgiving -- the PRI was brought back to power despite even more disastrous governments during the '70s, '80s and '90s. Should Peña Nieto's term fall short of expectations, perhaps the PAN's legacy in power viewed through the lens of 2018 will not be so dim after all.

Rodrigo Aguilera is an Editor/Economist covering Latin America for the Economist Intelligence Unit.