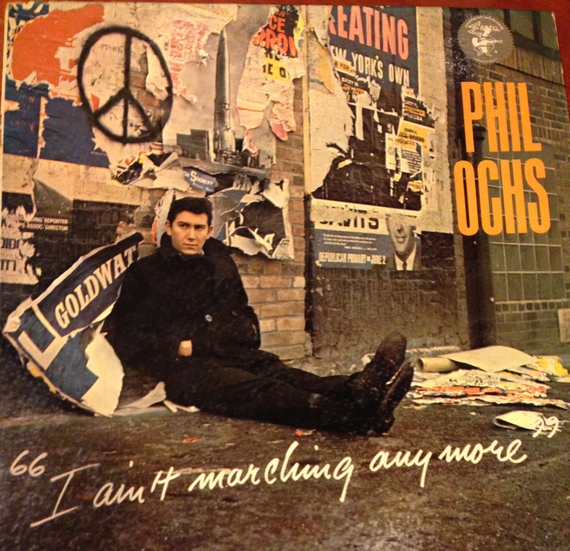

Phil Ochs has his own cluster in my vinyl albums, right between the Notting Hillbillies and Roy Orbison.

And in the lower right corner on the back cover of Phil's 1965 album "I Ain't Marching Any More," there is a small, neat inscription in red ink: "S. McMillin."

I knew Steve McMillin in high school. I never returned the album to him because I couldn't. Not too many years thereafter, Steve killed himself.

As did Phil Ochs, on April 9, 1976.

Had he survived, he would be 75, which doesn't seem that old any more.

Lotta water under the bridge in those 40 years, as Dooley Wilson remarked in Casablanca, and I can't count the number of times during those years when I've been talking with someone about the events of the world and one of us would say, "We really could use Phil Ochs."

We could. When he was on his game, in the middle 1960s, Phil Ochs could turn a situation into a song that distilled it down to exactly what mattered

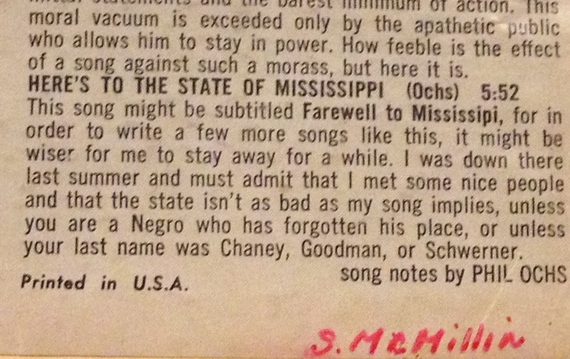

Sometimes his songs were angry, like "Here's the State of Mississippi" - "The sweating of their souls can't wash the blood from off their hands. . . ."

Sometimes they were sardonic, like "Outside of a Small Circle of Friends" or "Draft Dodger Rag" - "If you ever get a war without blood and gore / I'll be the first to go."

They could get preachy, like "Days of Decision" or "Links on the Chain." They could get sentimental, like "That Was the President."

Around 1967 Ochs starting writing longer. Before, he wrote articles. With "Crucifixion," "Pleasures of the Harbor" or "I've Had Her," he moved up to cinematic short stories.

After that he went back to something closer to the country and rockabilly with which he grew up. For that genre, "Gas Station Women" is a terrific song, brilliantly hovering just this side of parody: "Fill 'er up with love, please won't you mister / Just the hi-test is what I used to say / But that was before I lost my baby / I'll have a dollar's worth of regular today."

Many fans, and I wouldn't argue with them, think his best songs were the personal ones, like "When I'm Gone," "There But for Fortune" and "Changes," which today still sound hauntingly wistful.

"Sit by my side, come as close as the air . . . ."

He called himself, accurately, a journalist who happened to work in the song form. He wrote about the world around him with the eye of not just a journalist, but a very good journalist.

Okay, every song wasn't a win. "White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land" was well-intended and not very poetic.

Also, he was not Bob Dylan. He didn't have that same gift for words and images, which is not an insult. In an era that turned out first-rate folksingers and singer-songwriters the way Ford turned out Mustangs, no one else was Bob Dylan.

It was okay that everyone else, from Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez and Eric Anderson to Ian and Sylvia, was playing for second place. They produced their own music and the best of it was wonderful. Not a word of apology was needed.

But Ochs knew well Dylan enough to carry the matchup around with him, which was not good because he was also carrying an additional, heavier cross.

He was bipolar, like his father Jacob, and by the time he was 30 that condition and the pressures of life had propelled him on a downward spiral he was able to arrest only for ever-briefer moments

His younger brother Michael, who managed his career for a time, said in an interview a couple of years ago that today there would probably be pharmaceutical solutions. Then, there either weren't or he didn't get them.

So on a windy overcast day at his sister Sonny's house in Far Rockaway, Queens, he wrote the last verse of "When I'm Gone."

Phil Ochs's last years, by all accounts, were dark. We don't really know what he thought of the world he was leaving.

We do know that a decade earlier, he still harbored some of the spirit of Woody Guthrie, for whom he wrote a memorial song, "Bound for Glory."

As a newspaperman, Ochs saw too much things he didn't like. But that bothered him, from all we can tell, because he thought they didn't have to stay bad. They could be made better.

So for years he climbed on rickety platform trucks at anti-war rallies, "singing louder than the guns." You don't work that hard to identify the problem unless you think it's possible to implement the solution.

I didn't know Phil Ochs, of course. I did know Steve McMillin. He was tall and good-looking. He was a music fan. He had a sharp sense of humor and he was whip-smart. He went to Cornell.

I remember a conversation in which he was talking about potential, how it's so sad to have the ability to do something and then waste that ability by not doing it.

Let's call that conversation tragically ironic. I've thought the same thing about the "S. McMillin" in the neat red ink on "I Ain't Marching Any More."

Maybe it just shows that no matter what we want to erase, we leave something anyway.