Only a few days left: New York Fashion Week is sprinting toward the finish line.

For the most part, we've been seeing the usual fare: blaring music accompanies a line of stern, match-thin fifteen-year-old girls marching up and down the runways: the editors and buyers seated in the front rows look studiously unimpressed, while bloggers giddily rubberneck from the standing areas. Months of hard work are distilled down to this noisy, frantic twenty minutes and these thirty-or-so outfits. The last model disappears backstage; out pops the designer for a self-effacing little bow, and - just like that - the show is over. Hundreds of people crush toward the exit and move on to the next show.

These days, the fashion industry seems synonymous with this sort of bi-annual, adrenaline-pumped, front-row culture - yet fashion shows of this ilk are a relatively recent phenomenon.

In eras past, the designs of the day were presented to clients at chic poolside presentations or at delightful little department store luncheons (Waldorf salad, rather than global outreach, was the order of the day). Models strolled through department stories, wearing the in-house designer's latest and greatest creations (I was enchanted to learn recently that my own mother, while studying piano in 1960s New York City, moonlighted as an in-house fur coat model at Bonwit Teller - how Mad Men can you get??).

To learn more about the history of fashion shows in America, I called Valerie Steele, the venerable director of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. In this special edition of Let's Bring Back -- my longstanding column that celebrates forgotten objects, rituals, curiosities, and personae -- Ms. Steele offers a colorful overview of how American women "met" their clothes in bygone eras.

* * *

The Nineteenth Century:

Transatlantic Shopping Benders and Purloined Patterns

It sounds like in the early years of our country's history, the term "American fashion" was an oxymoron. In the 1800s, wealthy clotheshorses braved the icy Atlantic and beelined for Paris. "There's a funny poem, called 'Nothing to Wear,'" says Steele, "in which Miss Flora M'Flimsey of Madison Square goes over to Paris and buys all of these clothes."

...Bonnets, mantillas, capes, collars, and shawls;

Dresses for breakfasts, and dinners, and balls;

Dresses to sit in, and stand in, and walk in;

Dresses to dance in, and flirt in, and talk in;

Dresses in which to do nothing at all.

Miss M'Flimsey then cleverly smuggles these trunkloads of goodies into country to avoid paying customs. These shopping voyages were typical especially in the second half of the 19th century, in the era known as the "Gilded Age."

Poor little Flora had nothing to wear

In addition, Steele says, there were gaggles of "foreign fashion magazines and American fashion magazines which would buy -- or steal -- fashion plates from French magazines and sometimes modify them for an American market." By then, she continues, "you had people ... distributing dress patterns with the fashion magazines or separately. And although they were immensely complicated, it did mean that home sewers or local dressmakers could put together some facsimile of a Parisian fashion dress."

Not everyone was thrilled with this chic influx of feathers and finery. "There were a lot of complaints in the press," says Steele, "about how could the daughters of Puritan ancestors be dressed by man milliners in [France], who were basically dedicated to dressing demimondaines [courtesans] in the wicked city of Paris? But despite all of these diatribes about how Americans should be wearing virtuous, democratic, Puritanical fashion, in fact, they're wearing French styles."

Early 1900s:

Daily Department Store Shows and Nameless Designers

Keen to claim a cut of the business flowing to the continent, American department stores began to host in-house fashion shows in the late 19th century, sometimes every day. "It wasn't like now, where it's for buyers and editors," says Steele. "In those days, [the shows] were for clients or would-be clients. Ladies would come in and sit on little chairs at tables, and you could smoke and drink and watch the models wearing the clothes. Sometimes there would be music. It was very low-key compared to what we [now] think of as fashion shows."

A Bloomingdales of yore

The creators of these wares, however, largely remained anonymous: unlike the bold-face-name designers of today, the late 19th- and early 20th century seamstresses and tailors were largely squirreled away in the back of the store. The Paris couture houses bore the names of their designers - such as the House of Worth, for example - but "if there were any names mentioned in America, it tended to be the name of the store," says Steele.

The 1930s, '40s, and '50s:

America Designers Gun for the Center Stage

In the 1930s, American designers became fed up with their place in the shade and launched the American Designer Movement. "People like Dorothy Shaver at Lord & Taylor, promot[ed] the idea that you had dresses by American designers," says Steele. "[American designer] Claire McCardell was one of the first who went to Paris, [where] she looked at Parisian clothes ... and tried to figure out, could she simplify this kind of design so it could be mass-manufactured at a much lower price for a more democratic market." McCardell insisted that her name was sewn onto the labels of her apparel designs; she was a pioneer in doing so.

Claire McCardell swimming suits, mid-1940s

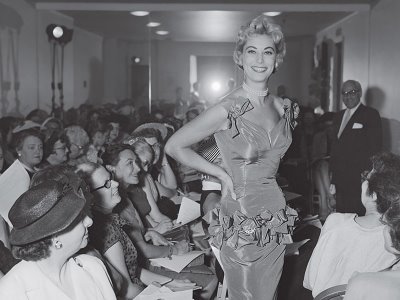

By the '40s, American designer Norman Norell, who specialized in upscale ready-to-wear clothing, had set up an elite atelier in the European tradition. "There would be a Paris-couture style fashion show," says Steele, "[With] little gold chairs, people in evening dress, ashtrays around. There would be editors and buyers, but there'd also be private clients. Norelle would be there, sending out these tall, glamorous gals wearing the clothes."

Norelle's "tall, glamorous gals" would likely look very out of place on today's runways: "They wouldn't be as young as [today's models] are," says Steele. "They'd probably be like 28 instead of 15 ... [and] many of the clients would have been older than that. You hadn't had the whole 1960s Youthquake yet, so you didn't have this transition to the idea that the most desirable, most fashionable women were teenagers or twenty-somethings."

While World War II temporarily decimated Paris as a fashion capital, it helped place New York on the map. "Once the Nazis occupied Paris, then the US and the allied countries blocked access to Paris fashion news," says Steele. "The Americans were thrown very much back on themselves and had to really start depending on American designers and promoting American design." Capitalizing on this turn of events, now-legendary American fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert launched "Press Week for Seventh Avenue" in 1943, biannual event that showcased American fashion to the international media, and precursor to today's Fashion Week.

A catwalk from New York's first fashion week in 1943

When the war ended, however, Parisian designer Christian Dior introduced the New Look in 1947 and kicked the uppity Americans back off the center stage for nearly three decades.

The 1960s and '70s:

Free Form on the Runways

Following the very grown-up and comparatively prim 1950s, pop culture served up an international "Youthquake" that gave the first inkling of today's youth-centered fashion industry. The Youthquake's ground zero was London, and waif model Twiggy and the Beatles were among its patrons saints. "That was something really new," says Steele. "When someone like Mary Quant (an English designer credited with inventing the mini skirt and hot pants) would come over to New York and go to Macy's, there'd be a big fashion show with mini dresses and lots of young clients."

Twiggy, the face of the Youthquake

While the French were thrown for a loop ("They didn't have a Youthquake," says Steele), the American fashion industry happily took the phenomenon in stride. In the mid-seventies, a group of American designers - including Halston - took part in a series of Franco-American shows as Versailles.

"The French staged a formal, elegant fashion show," says Steele. "And the Americans had music playing and the girls came out dancing: almost a sort of proto-disco show, practically free-form, bouncing down the runway. It was all about movement. That really moved the trend along: instead of just having a little jazz band playing in the background, you've got rock 'n roll, you've got disco. And those models in the '70s could really move."

The 1980s to the present:

Big Top Fashion Gives Way to Models Anonymous

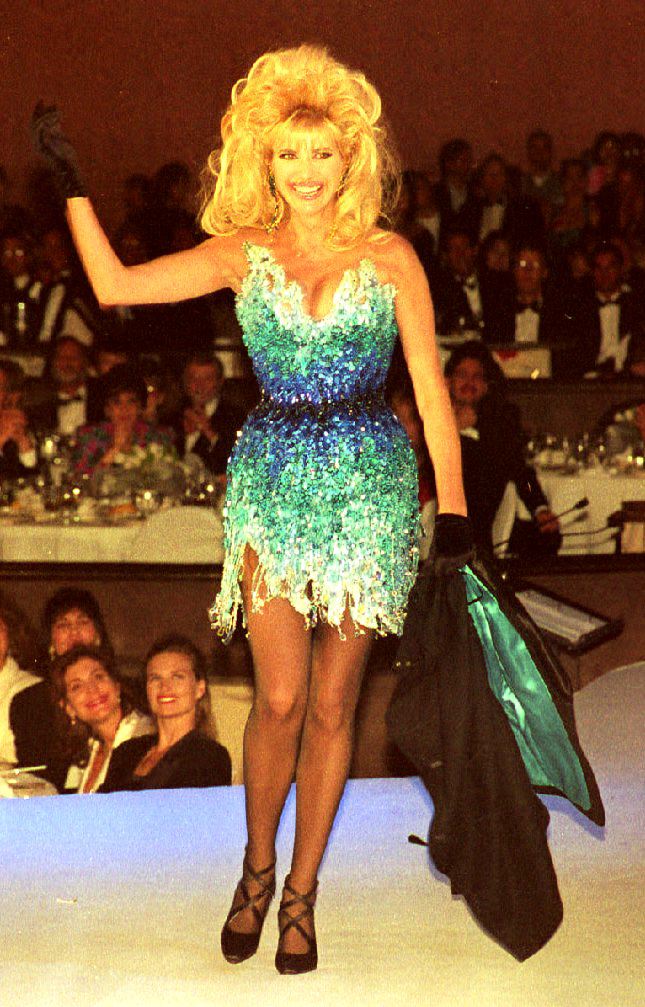

As designers moved away from relationships with individual clients and the industry became more focused on servicing the mass market, fashion shows were increasingly staged for buyers from retailers and editors. In the 1980s, Fashion Week theatricality reached dizzying heights, and shows became a way to project a brand to millions of people. Then models like Linda Evangelista and Naomi Campbell were turned into international superstars, and runway shows became globally-watched attractions.

Ivana Trump whoops it up on an 80s runway

"A handful of London designers really pioneered ... the big extravaganzas: Thierry Mugler was famous for this sort of circus-like performance," says Steele. "They got more and more elaborate and more pyrotechnic."

Yet even in the gluttonous '80s, only a handful of design houses could afford to stage such spectacles, and most of today's major American shows - while still elaborate productions - have adopted a more regimented, homogenous presentation. "In the U.S., Marc Jacobs is practically the only one who [still] habitually does [big shows]," says Steel. "They're more typical of Paris."

Also, it apparently occurred to designers in the 1990s that such Big Top brouhahas might just be distracting their consumers from the real stars of the shows: the clothes. "Although [theatrics] can work for some designers, it seemed, particularly for American designers, both less expensive and more focused to just have the emphasis on anonymous-looking models, models-as-clothes-hangers," says Steele.

The Future of Fashion Shows?

More and more, one hears whispers that the Internet will doom the runway show to the ashbin of history. Fashion shows remain prohibitively costly to stage - and why go through the bother when a designer could simply photography a collection and email it to countless editors and buyers around the world?

"The idea that ultimately the Internet is going to take over is probably true in the long run, but it will probably be a jerky path to get there," says Steele. "Just as it's been in terms of buying clothes on the Internet. You really need to see what it looks like on you. Certainly buyers and journalists want to see the atmosphere: what do your colleagues think? Are people excited? You want to go backstage and touch the stuff: how well made is it? It's very hard to picture on the Internet, to get a sense of it, compared to being there."

Yet, in some ways and parts of the world, technology is bringing consumers back to the early days of fashion shows. "In Japan, you have things like Tokyo Girls collections, where consumers go in," says Steele. "They have a big production and you can order on your cell phone the things that you want. In a way, it's swinging back to [the model of] bringing it back to the customers."

Now - that's what you'd call an updated classic.

A Tokyo Girls Collection presention

* * *

Special thanks to Ms. Steele for her delightful interview.

* * *

In Fall 2010, Chronicle Books will release a book by Lesley M. M. Blume based on this popular column. 'Let's Bring Back' will be a sophisticated, stylish cultural encyclopedia, celebrating forgotten objects, pastimes, and personae from bygone eras. From sealing wax and quill pens to the Orient Express, fainting couches, and limericks, there is a great deal of ground to cover. Please make sure to visit previous installments of Let's Bring Back.