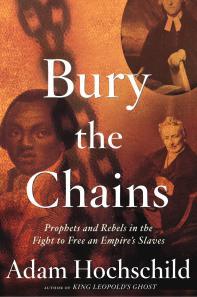

I am reading Bury The Chains by Adam Hochschild.

It's an outstanding book, which is not surprising, as Hochschild is the author of (amongst other things), King Leopold's Ghost -- the history of the Belgian Congo, and To End All Wars, which I personally think is probably the best book about the First World War that I have read.

Bury The Chains is the story of the fight to end slavery in the British Empire at the end of the 18th Century. Slavery was so deeply embedded in the economic fabric of both Britain and the Empire that, as Hochschild writes

If, early that year [1787] you had stood on a London street corner and insisted that slavery was morally wrong and should be stopped, nine out of ten listeners would have laughed you off as a crackpot. The tenth might have agreed with you in principle, but assured you that ending slavery was wildly impractical; the British Empire's economy would collapse.

Hochschild's portrayals of the condition of African slaves brought to the West Indies to be worked to death, quite literally, on the sugar plantations makes Twelve Years A Slave look like a stay at a Four Season's resort.

Perhaps most astonishing to me, in a book filled with astonishing facts, was the revelation that George Washington, (and other 'Founding Fathers'), whilst fighting so eloquently for 'freedom' and 'rights' for the citizens of the new 'United States', were also busy fighting for the 'return of their property -- their slaves'.

During the American Revolution, the British issued a proclamation promising 'freedom to any slaves, male or female, who deserted a rebel owner by crossing into British-held territory'. (Hochschild p. 99).

Thousands did.

When the war was over, some slaves decamped with the British for England. Others were recaptured by their former owners. However, some 3,000 found themselves in New York, under the protection of the soon to be departing British army.

What to do with these former slaves became a major issue in the Paris Peace Conference of 1782, the formal terms of the separation of the U.S. from Britain.

General George Washington, the American commander, insisted upon the immediate return of the 'property.'

He forwarded to his representative in New York a long list of runaway slaves and asked for help in 'securing them... if they are to be found in the City.... Some of my own slaves.. may probably be in N York. If by Chance you should come at the knowledge of any of them, I will be much obliged by your securing them." (Hochschild p. 101)

The British Commander, General Sir Guy Carleton, however, was not about to turn the slaves over the Americans nor to Washington. In New York they were still under his protection. This annoyed Washington no end.

Washington 'delivered himself without Animation, with great slowness and a low Tone of Voice'. Item One, Washington told Carleton, was 'the Preservation of Property from being carried off, and especially the Negroes'.

Carleton replied that he could not return 'the property' as they had already embarked on British ships.

"Already embarked!" replied Washington, greatly annoyed.

While the negotiations were proceeding, Carleton has placed the freed slaves on a British ships and sent them off to Nova Scotia, where they would become, for a time, the largest community of free black men and women anywhere in the British territory of the Americas.

It took Washington a long time to relinquish his claim to his lost 'property', and after many years he shifted to asking for compensation instead of their return. In 1826, Britain agreed to pay the slave owners or their heirs half the market value of their former slaves.