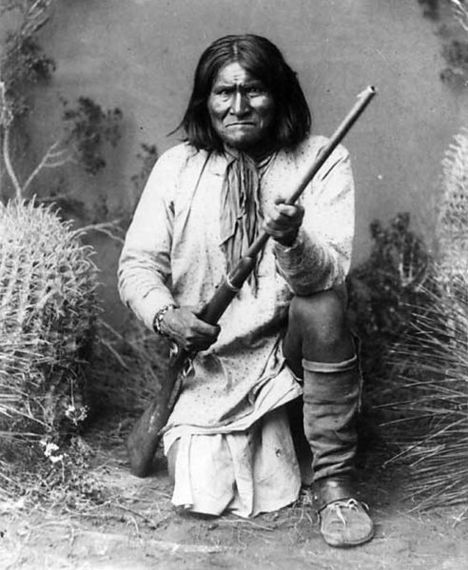

The United States hunted Apache leader Geronimo for years during a blood-soaked era, when both sides had a lot at stake and considerable hostility towards each other. Geronimo would recede into the crevice-rich Sierra Madre Mountains to elude capture, sometimes entering caves and exiting through an alternate opening that U.S. troops were never able to find, even after the fact. The pursuit of Geronimo was so intense, protracted and bitter that when President Obama decided to go after Osama bin Laden in a garrison town of Pakistan, he is said to have named the operation Geronimo. What's more, when Fox News was preparing its documentary on Robert O'Neill, the Navy Seal who claims to have delivered the fatal shots to bin Laden, it gave the program the code-name of Gatewood after the Army commander who took custody of Geronimo in 1886.

But the truth is we can only peer back those 128 years with a sense of wonder, bordering on disbelief. Indeed, there are stark differences between the pursuit of Geronimo and the bin Laden operation. And those differences tell a story. What's more, O'Neill is not much like Lieutenant Charles Gatewood. The approach that U.S. officials used with the Apache chief seems more than unattainable today. It appears foreign.

U.S. officials demonstrated a tolerance and forbearance in dealing with Geronimo that wouldn't stand a chance of prevailing today, against a similar "hostile." And even if the United States wanted to establish such restraint and greater civility, it is today confronting an enemy that harbors an animus that overshadows even that of this stalwart Apache warrior, who lost everything to white settlers. The hostility facing U.S. troops, aid workers and contractors in the Middle East is more reactive, swifter and deeper than anything the country has faced before, even when it took over--sometimes brutally--the land of native people. And because military missions in the Middle East entail a building-up simultaneous to, rather than in wake of, vanquishing an enemy, that enmity is especially consequential. Indeed, it is probably insurmountable.

The tale of Geronimo and the restraint with which U.S. officials allowed themselves to treat the Apache warrior brings us back to simpler times, when a straightforward belief in duty and an abiding respect for people different from ourselves--even when they had done us wrong--could drive action and policy. This is important to remember because much of the shoot-'em-up, drone- 'em-good crowd often tries to appropriate America's past to justify their actions. Many resort to contorted interpretations of the Founders. But so often, American history contradicts that cause. Consider the tale of Geronimo:

Geronimo was put on the warpath after Mexican troops invaded his village and killed his elderly mother, his wife and small children while he and other braves were trading goods. Geronimo, whose real Indian name (Goyahkla) translates into One Who Yawns, was awoken from his sweet somnolence by the tragedy. He told his biographer: "Within a few days we arrived at our own settlement. There were the decorations that Alope [Geronimo's wife] had made--and there were the playthings of our little ones. I burned them all, even our tepee. I also burned my mother's tepee and destroyed all her property. I was never again contented in our quiet home."

Many innocent people paid the price for Geronimo's restlessness. His desire for revenge exceeded that of other Apaches. Some of his own people blamed him for campaigns that were deemed disproportionate, unnecessarily causing the death of many good warriors. We don't have an exact death toll of Geronimo's murder spree, but he was a merciless to the whites who pursued him, or just crossed his path.

Despite Geronimo's known ruthlessness, in 1872 he was corralled onto a reservation in the mountains with other Apaches and allowed to live there in peace. Geronimo escaped the reservation, opting instead to lead attacks on white settlers. In 1884, Geronimo and members of other Apache groups surrendered and were taken to the San Carlos Indian Reservation. But shortly thereafter, Geronimo escaped again, along with 144 others. He surrendered again to U.S. authorities ten months later. Geronimo and a small band escaped once again, fearing they would be murdered.

He was then hunted for over 1,645 miles by over 5,000 men. At the last leg, though, it was just Gatewood, his Apache interpreters, and a handful of escorts who were present. Geronimo's band descended the mountain to meet them, then vanished, only to explode out of the bush from different directions. Gatewood was surrounded by 35 to 40 Apaches. Gatewood greeted the group, took off his arms, and shared tobacco with the Apaches. As everyone started to smoke, Geronimo appeared and set down his Winchester.

"How are you?" Geronimo asked Gatewood. Before he could answer, Geronimo commented on the lieutenant's thinness and apparent bad health and asked Gatewood, who had led the arduous search for the Apache renegade, what was the matter. Gatewood negotiated, smoked and broke bread with Geronimo until the night, at which time Gatewood left with no agreement from Geronimo. In the morning, Gatewood returned and Geronimo said he would surrender to Gen. Nelson Miles. Some call it a capture because it was a surrender under duress, thanks to Gatewood's pursuit. Miles later described Geronimo as "one of the brightest, most resolute, determined-looking men that I have ever encountered [with] the clearest, sharpest, dark eye I think I have ever seen."

Geronimo lived his last days in Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma. After his capture in Arizona, he was always considered a prisoner of war but still married numerous times, had several children, narrated his life story that included many of the many brutal injustices that the Apaches suffered, rode in President Roosevelt's inaugural parade, had a private audience with Roosevelt, and starred in expositions and fairs. U.S. officials never lost sight of Geronimo's past ruthlessness, though, and he was never allowed him to return to his native Arizona, although he pleaded with Roosevelt to be allowed to do so.

This is not to suggest that bin Laden and Geronimo are equivalent and that the former should be treated with any deference. The acts of 9/11 were not only crimes against humanity, they are a stain on humanity. And bin Laden's acts were not only cruel, they were also cowardly in every sense of the word. Bin Laden, unlike Geronimo, never engaged U.S. soldiers himself. Indeed, as O'Neill has said, at his moment of reckoning, bin Laden stood behind his young wife, his hands on her shoulders.

But given the country's mood today, would any civility even be possible against an enemy? Many have argued that even suggesting such conduct is un-American, although the story of Geronimo (and many others that I will offer as the news cycle permits) attests otherwise. The idea of restoring any sense of humanity towards any of our Muslim adversaries today seems out of reach.

Our enemies, in turn, don't trust any Western interlocutor to represent their interests. As reported, even the moderate Muslims that the United States has supported in Syria traded American citizens Foley and Sotloff for a fistful of cash to ISIS beheaders. And still Gen. Martin Dempsey continues to talk about "moderate" fighters the United States can partner with in Syria.

The United States was correct in bringing bin Laden to justice. If the Navy Seals claim that they could not have brought him back alive under the circumstances in which they were operating, then so be it. But given current temperaments, many influential Americans would be opposed to a trial for bin Laden at any rate. That is a shame, because the spectacle of the U.S. justice system adjudicating bin Laden would have traveled the world. And like Geronimo's story, that would have provided a forceful argument in and of itself, in this ongoing, global competition for hearts, minds and sensibilities.

The author of Geronimo's biography, S.M. Barrett (Superintendent of Education in Lawton, Oklahoma), said in the preface:

"The initial idea of the compilation of this work was to give the reading public an authentic record of the private life of the Apache Indians, and to extend to Geronimo as a prisoner of war the courtesy due any captive, i.e., the right to state the causes which impelled him in his opposition to our civilization and laws.

There seems today such a slim chance that we could extend to one of our current detainees the "courtesy due any captive" to explain "the causes which impelled him in his opposition to our civilization and laws." True, it is easier to do so once we have already won. But on this point, we should perhaps heed the words of Navy Seal O'Neill, who pointed out that America's enemies in the Middle East often scatter once U.S. forces arrive, waiting on the sidelines for their departure to carry out violent campaigns. In light of that, would O'Neill and others have us in Iraq, Syria and God knows where else in perpetuity? If so, how and when is the United States expected to pack up its surveillance state, military industrial complex, and bravado?

O'Neill's own organization, "Your Grateful Nation," seeks to help those troops that want to put down their gun and start life anew. That is a laudable goal. Isn't it time our country did the same, conclusively?

Bin Laden's corpse has long been a trophy, brandished to push forward all manner of policy and philosophy. True, no one is brandishing the bloody scalp. But are we really so far from that?