Cities Go Green

A number of American cities are looking at innovative and creative ways to develop new park land for their residents in projects which can also help protect their local streams and rivers from the type of dirty water and even raw sewage overflow caused by heavy rainfalls.

These projects are known as green infrastructure, and while Philadelphia and New York have some of the largest such projects in the works, other cities are following a similar path:

•Boston has a plan which will restore the Back Bay Fens planned by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 19th Century. The first phase will fix 3.4 mile-long Muddy River and its shorelines, alleviate flooding, restore the river habitat, and "daylight" parts of the watercourse that have been hidden in huge culverts for decades.

•Washington, D.C., is commencing a $2.6 billion Clean Rivers Project, including green infrastructure park projects, to with a 2005 consent decree with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Already, Canal Park is being recognized for its innovative stormwater management, and the National Mall (article in Landscape Architecture mag?) has also become a green infrastructure force. The Mall, known as "America's front yard," is being renovated for the first time in 40 years.

•Bellevue, Washington, was an early pioneer in a storm water management partnership between its water district and parks department, where the "Utility" purchased the land and built storm water management features, and the parks department built and maintained recreational facilities at each location. For example, where a storm water vault was built, the parks department would place a tennis court over it; elsewhere, a storm water detention basin would also function as a soccer field.

•In New Orleans, the Trust for Public Land has worked with local officials to acquire a significant first portion of land that will eventually be part of a 3.1 mile "Lafitte Greenway," a trail running from the French Quarter to the Lakeville area and Lake Pontchartrain. A design developed by landscape architect Dan Waggoner envisions not just a traditional bicycle path, but also a complex series of green infrastructure interventions that would help New Orleans manage storm water runoff -- a crucial issue for this low-lying city with a history of flooding, such as happened from Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

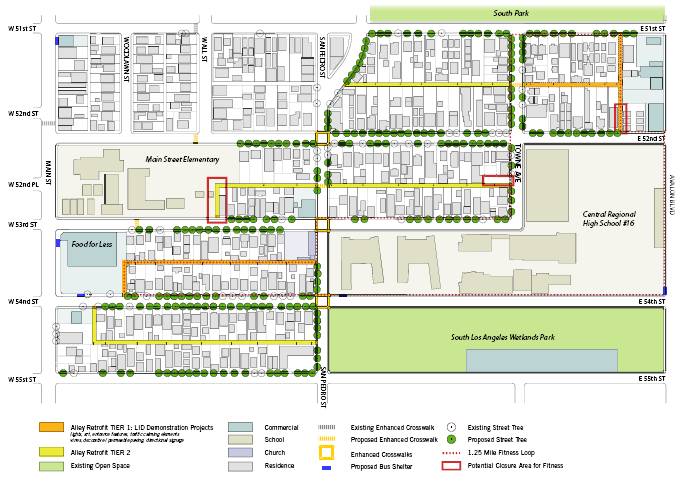

•Los Angeles officials are looking at turning many miles of impervious alleys into "Green Alleys" where light-colored pavement could help alleviate the urban heat island effect, and planting beds could serve as rain gardens to capture storm water.

•Chicago is successfully moving forward with its own Green Alley Program, introduced in 2007 to convert more than 1,900 miles of asphalt and concrete public alleys to 3,500 acres of permeable paving, with the goal of reducing storm water by 80 percent.

Site of and future plans for the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans. Image courtesy of The Trust for Public Land.

Rendering of a Green Alley in Los Angeles. Image Courtesy of The Trust for Public Land and SALT Landscape Architects

Map of planned Los Angeles Green Alleys. Image Courtesy of The Trust for Public Land and SALT Landscape Architects

While green infrastructure has mostly been defined as a natural approach to storm water management, increasingly, landscape architects, engineers, geophysicists, planners, and officials are considering natural approaches to creating both barriers and mitigation zones to address the effects of ocean and river storm surge. For example, Fitchburg, Massachusetts, removed a floodwall from the North Nashua River and created a riverfront park on a "brownfield," the term used for a polluted industrial site.

Even before the disastrous impact of storm surge in 2012 from Superstorm Sandy on New York City, professional designers and engineers had formulated ideas to deal with potential problems. They had known for years the low-lying areas of New York City would be vulnerable to storm surge damage from both wave action and flooding, and it that it was just a matter of time before "the Big One" hit and flooded neighborhoods, highways, subway and automobile tunnels, and other crucial infrastructure.

Global climate change, rising sea level, and green infrastructure

In the prescient "Rising Currents" exhibition mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010, teams of local landscape architects and architects developed new approaches for addressing rising sea levels and flooding storm surges in New York. Based on a two-year research project by the engineer Guy Nordenson, the landscape architect Catherine Seavitt and the architect Adam Yarinsky, the exhibition (curated by Barry Bergdoll) showcased what appeared to be radical thinking about how to soften the traditional hard edges of the city's interface with its harbor waters.

The ideas included recreating the historic salt marsh verges of the city, excavating "slips" that allowed the harbor waters to penetrate the street grid, building two-way porous streets, constructing apartment complexes in Venetian style water settings, and otherwise subverting, including with oyster beds the traditional approach to harbor waters -- to build strong, rigid, vertical structures and walls, which work fine until the water goes higher than the hard edge.

Now, as the city recovers from the devastation of Sandy and considers options for preventing or mitigating the effects of both gradual sea level rise and catastrophic storms such as Sandy, officials at the highest levels of government are considering both very expensive, gray infrastructure responses including dikes, levees and barriers; but also green infrastructure approaches, including engineered salt marshes, constructed dunes, and other "soft" systems to mitigate the flooding and storm surge damage. The City of New York recently released a massive set of recommendations to address storm surge and flooding. The U.S.government has also come up with its own recommendations, as has the State of New York. Like the expanded flood plains created next to rural rivers that flood regularly, these green infrastructure elements can also function as parks, greenways, and natural areas, providing public space for humans and vital habitat for animals.

It is clear that green infrastructure will be part of the future solution to manage that most vital and also most dangerous of all natural forces -- water.

A longer version of this article was originally published in "The Nature of Cities" blog. Marianna Koval, a consultant for the Trust for Public Land, provided research on the use of Green Infrastructure in parks, some of which is incorporated in this piece. Additional assistance was provided by Cecille Bernstein, also of The Trust for Public Land.