A select number of developers, jailbreakers and pirates are setting their sights on the Kindle, coming up with some surprising software and websites for the barebones device.

If Jeff Bezos wants, a few cease-and-desist letters could stop many of what might loosely be called the Kindle hacks -- but he would be killing off a valuable cottage industry.

The Kindle is a machine for buying books from Amazon. The giant online retailer has single-mindedly engineered it to execute that single activity. Anyone who has ever spent a half hour with it realizes that it displays books and the Kindle storefront very well, and doesn't do much else. (Jason Kottke has gone so far as to claim that the "Kindle is more like a 7-Eleven than a book.")

Its limits are intentional. Jeff Bezos has quite explicitly stated that he is not trying to compete against the multipurpose iPad head-to-head, and instead is positioning the Kindle as the market leader among dedicated ereaders.

But that doesn't mean there isn't a little wiggle room for outsiders to stretch the Kindle's capabilities beyond what Amazon advertises. And the Kindle's very limitations -- its black and gray screen, slow refresh rates, cumbersome keys and limited internet capacity -- make it a paradoxically appealing target for a certain breed of geek who gets a thrill out of making limited hardware over-perform.

Making Reading Easier: Instapaper, Kindlefeeder and Calibre

The best contributions from the Kindle hackers use a clever bit of developer jiu jitsu to turn the device into an extension of the internet that strips away its irritating distractions. They quite literally make the web a more legible place.

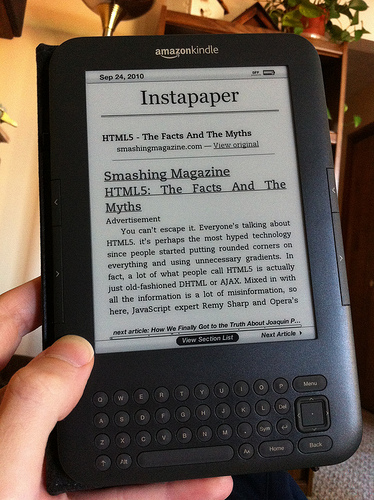

Foremost among them is Instapaper, the lavishly and justly praised website-app hybrid that stores long articles (or emails) and lets you read them on the device of your choice. What Instapaper does, brilliantly, is not just store these articles, but store them without all the widgets and sidebars (and ads) so inescapable on the web today.

The Kindle very neatly complements Instapaper's calm aesthetic. The very technology the Kindle uses to present text, E-Ink, averts the eyestrain so common with liquid crystal displays. Instapaper's one-man development team, Marco Arment, has written that the "iPad is a great casual computer, but the Kindle is the superior reading device."

Image by Joshua Kaufman

One obvious limitation to Instapaper is that it doesn't capture full RSS feeds, the subscriptions that often allow readers to get a rolling catalog of latest articles from blogs and news sites. That's no accident. Arment was motivated to create Instapaper in part out of frustration with "the quick-consumption nature of many devoted blog readers. Authors are encouraged to cater to drive-by visitors hurrying through their feed readers by producing lightweight content for quick skimming."

Not all may agree with Arment's criticism of RSS. What's more, there are plenty of RSS feeds one can't just hurry through. Neither the Paris Review Daily nor the New York Review of Books blog work well with a traditional reader, but saving each individual article on them to Instapaper would be a tiresome and decidedly un-simplistic activity.

For those who have to have feeds on the Kindle, Amazon has a subscription service for blogs. In my experience it doesn't do a great job displaying images. But that's just a technical problem; Amazon's blog subscriptions have two far more dramatic drawbacks. First, there are only a limited number of sites available. Bloggers have to sign themselves up. Second: you have to pay. That's anathema pretty much anywhere on the real web, but in the limited context of the Kindle, Amazon figures it can charge. After all, the company does have to pay for the Whispernet service that lets Kindle 3G owners download books and blogs from anywhere. But paying for a blog, and a blog that won't even show you an embedded video, could certainly leave you feeling like a chump.

A fine alternative is Kindlefeeder, a website created by software developer Daniel Choi. First generation Kindles didn't have a subscription feature for feeds, so Choi created Kindlefeeder. It emails Amazon a package of feeds that are then passed along to the Kindle. And, critically, you can automate the delivery of Kindle emails -- so you can get a raft of new blog posts sent to your Kindle every morning. Kindlefeeder makes reading RSS feeds a surprisingly uncluttered affair.

Kindlefeeder has had about 11,000 signups, a small number in the context of the estimated 8 million Kindles sold last year.

Updates to Kindlefeeder have been rare. Choi says the Kindle's unclear terms of service, which may prohibit automated delivery of feeds, have left him with little motivation to spend time working on Kindlefeeder. He's written to Amazon's legal department -- and not heard back. "Why not just make a service like Kindlefeeder completely legitimate?" he asks, "I just don't understand that." For now, Choi says, there's a "cloud that's hanging over it."

Choi isn't the only developer who questions Amazon's decisions on Kindle openness. Kovid Goyal, the lead developer behind the open source ebook management application Calibre, argues, "it's not so much that they actively want to lock people into their devices, but more that they just don't recognize the value to their customers in opening up their device."

Goyal's Calibre allows owners of just about any ereader -- not just the Kindle -- to manage their collections of ebooks and convert between the open standard .epub format used on Sony and Apple devices and the Kindle's proprietary format. Equally impressive, Calibre does a fine job of converting PDFs, which are as finicky a document format as exists. Amazon offers a less capable PDF conversion alternative (and its slow-selling Kindle DX lets you read full-page PDFs at their full size).

Calibre also enables people to edit the metadata -- like author names and book titles -- that Amazon bizarrely locks down on the Kindle. Amazon includes no management software like Calibre with the Kindle, forcing users to rely solely on in-Kindle features to find and organize books and more.

"They made a system that works very well as long as you don't stray from the Amazon walled garden," Goyal says.

Pirates and Jailbreakers: DeDRM and KIF

Out in the electronic ether exist a number of programs and scripts that promise to remove DRM (digital rights management) copy protection from ebook files, allowing you to, for instance, read a Kindle book on a Sony Reader. It's a pretty niche need right now, and of questionable legality even when you're just trying to get an ebook you already own to work with your Kindle.

Moreover, it's worth noting that, much to its credit, Amazon has made it extremely easy to store backup copies of your books on its servers in the cloud, from which they can then be read them on the multitude of Kindle apps for computers, iPads, and Android devices.

Another activity sure to irritate Amazon's legal department, and one which may at the very least void your warranty, is jailbreaking the Kindle so it can run unauthorized code. The most useful thing jailbreaking allows is changing the screensavers the Kindle displays when you've turned it off. You can add pretty much any image you want -- for example a classic bookplate with your name Photoshopped in.

A handful of software companies sell "Kindle Active Content." On any other platform these would be called apps, but Amazon seems to be avoiding unflattering comparisons to the rich multimedia programs available on the iPhone. For the Kindle, graphically unintensive games like Blackjack and Scrabble are top sellers.

Amazon seems to be stingy with access to its developer kits, so some coders have taken to jailbreaking Kindles. Andrew de Quincey, a Scottish software developer, says, "I find it a pity they didn't create an official way for interested people just to try random things out on the Kindle, but as I found out, they've not made it that hard to do so unofficially."

De Quincey has created a program, KIF, that will let Kindle owners play text adventures -- a state of the art technology in the 1980s (remember Zork?). Text games seem well-suited for the Kindle, but as de Quincey admits they have not much more than niche appeal these days.

As for jailbreaking in general, de Quincey thinks it likewise makes sense only for a few: "I don't really see the point unless there's a specific thing you actually want to do."

Sharing: Bookborrowr and Kindle Lending Club

One more Kindle innovation is on the horizon. On December 30, Amazon rolled out lending for Kindle. Publishers must consent to letting their books be shared, which avoids potential copyright issues.

A number of sites now hope to take advantage of book borrowing. One is called Bookborrowr, and its creator intends for it to work as a social community for people who need never have met to lend books to each other. It's an interesting idea, a sort of library of your peers. Founder Ade Lack says, "The sharing of digital books in one form or another is a must for the future of publishing."

Publishers could conceivably be taken unaware by large-scale sharing among people who don't know each other. Lack says some publishers he's talked to are supportive of lending and others are "a little cautious," but that he has yet to speak with one "openly against" lending.

Another site in beta is Kindle Lending Club. CNET's Stephen Shankland wonders if its emphasis on making money for its founders will be "enough to raise Amazon's eyebrows."

For now, on book lending and on many other Kindle hacks, the retailer is only showing one expression: a poker face.