Advice columnist Ann Landers once remarked: "At age 20, we worry about what others think of us. At age 40, we don't care what they think of us. At age 60, we discover they haven't been thinking of us at all." That indifference may soon change as older adults become our country's largest demographic group. Younger generations will have to think a great deal about older adults. In particular, they will have to think about how seniors can participate as full-fledged contributing members of society.

Why should young people care about seniors' productivity? As I note below, the unprecedented gains in life expectancy of the longevity revolution will have profound effects on the future, not only of our older citizens but of younger ones as well. Indeed, their fates are intertwined.

Boosting seniors' economic contribution is no simple task, but one from which younger generations -- and seniors themselves -- will greatly benefit. The first step, as I explain below, is to harness senior power. But before we explore how to confront that challenge, let's look more closely at the demographic realities.

Why Seniors Must Participate In The Economy

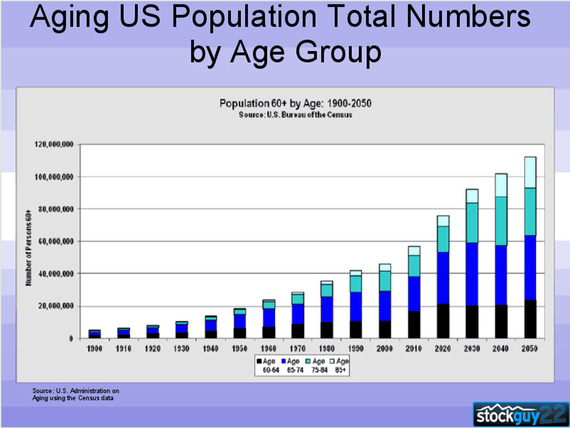

A child born this year has a good chance of living to 100. That's the good news. At the same time, the longevity revolution poses challenges. The further out we project the demographics the larger the older population and the smaller the younger population. How a vastly diminished workforce will support an explosively growing population of retirees is a critical economic conundrum.

With the coming of a dominant elderly population everything in the way we live, work, love, and play will change. That should not come as a surprise since it's well known that older people differ from younger generations in significant ways. Older adults often have particular philosophies of life, distinctive values, and priorities. Their tastes and preferences in fashion, television, movies, new technologies, consumerism, and every other arena of life can be strikingly different from those of younger generations. In addition to their increasing numbers, greater percentages of older Americans cast votes in elections than any other age group, giving them powerful influence on political outcomes. So the longevity revolution is not just about the economics of Social Security and Medicare.

The "Experts" Got It Wrong

Longevity sneaked up on economists and demographers. When Social Security was enacted in 1935 (the first recipients collected benefits in 1940) the age for receiving benefits was set at 65. Since life expectancy from birth at that time was 61.7, not everyone was expected to benefit--or not for long. But improved public health measures and the introduction of vaccines and antibiotics turned the tables on demographers.

Life expectancy at birth increased dramatically to an average today of 78.8 (81.2 for women and 76.4 for men)--and climbing. That explains why in the early years of Social Security there were forty workers for each retiree and now there are less than three--imposing an extraordinary and possibly unsustainable burden on the working population.

In fact, we are facing a new predictable demographic reality that will further widen the gap to less than two workers per retiree--and that is not based on crystal-ball gazing. Plain arithmetic tells it all. We can accurately predict the number of elderly over the coming decades based on the known numbers in the current generations. While we are certain that the older population will increase exponentially by mid-century and even more dramatically by 2100, one significant wild card is how long people will live in future decades, especially if there are breakthroughs in the cellular biology of aging and the genetic aging code. This X factor holds the potential to ratchet up the strain on future economies.

What can we do to meet this demographic challenge, when for the first time in the history of the world older adults, mostly retired, will be the largest group?

First We Must Recognize The Problem

And that means getting beyond the glib answers to the aging of society given by our politicians: "Just fix Social Security and Medicare." Unfortunately, that mantra has largely been the focus of the discussion over the past few decades--with little progress--and it continues today, as we have seen in the current political debates. None of the presidential candidates has recognized or addressed the bigger picture--and we close our eyes to that picture at great peril. The longevity revolution is here and the clock is ticking.We must start paying attention.

Fallout From Inaction

We are beginning to see the consequences of not effectively addressing the issues. Many politicians on the right would like to cut senior programs and some would savage them. Other ageist attacks demonize the elderly, accusing seniors of draining resources, utilizing far more medical procedures and services than other age groups--and the persistent overall complaint that seniors are takers not makers, that they are a burden and don't contribute to the economy or to society. Taking this position conveniently ignores the fact that seniors' work years produced today's prosperity, and that seniors paid for the benefits they are receiving.

Harnessing Senior Power--And That Means All Seniors

American seniors are generous volunteers through various programs and individual initiatives. In one of the largest programs, the Senior Corps RSVP, 300,000 seniors volunteer in numerous areas. While that is certainly noteworthy, even more impressive are the millions of other seniors sitting on the sidelines ready, able, and willing to volunteer. Volunteering, though, is not always a simple matter. You may have to navigate complex websites or work your way through a maze of referrals and phone calls that requires persistence and can be off-putting.

Unfortunately, we do not have an infrastructure to harness this vast reservoir of talent and energy that can make significant contributions to our economy and to our quality of life.

But a structure can readily be established. What's needed are facilities for signing up volunteers at easily accessible locations, in neighborhoods, malls, and other places that seniors routinely frequent. These can be storefronts, local businesses, such as banks, drug stores, department stores; also public spaces in libraries, schools, as well as religious institutions. Since store locations will bring a flow of traffic that will be good for these businesses they might even compete to be part of the program. Some businesses and corporations are already donating space for public programs. Boscov's department store in a Westfield Connecticut mall provides an auditorium for community use. Other businesses also offer free space. And surely a truly national senior volunteer program would inspire more businesses and corporations to pitch in with donated spaces.

All Seniors Register For Volunteerism On Retirement

On retirement seniors would be invited to register at these convenient sites, where they would be interviewed for appropriate volunteerism to the extent that they can participate. This would provide a comfortable personal setting where they can be seamlessly shepherded into volunteer roles.

Almost all seniors have some skill or experience to contribute that can directly or indirectly give a boost to the economy--e.g. mentoring students, young entrepreneurs, and small-business owners. Seniors with art and music backgrounds can restore school art and music programs that have been the victim of extensive cuts in education funding across America. Retired crafts and trades workers can help poor and low-wage workers with home repairs and renovations--and can teach them skills. The possibilities are endless.

Most important, this all-inclusive national senior corps will not only make a contribution to the economy, it will change the image of older adults from takers to makers, while incorporating seniors into the mainstream of American life. No other program holds as much promise for creating a society that will thrive and work for all ages.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is professor emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College) where he directed a graduate program in gerontology that spanned seven graduate departments. He is also the founder, and for 25 years, the managing editor of the cutting edge Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. He was also the editor of the Springer Publishing Company series Adulthood and Aging and another series Lifestyles and Issues in Aging. For three years he wrote commentary and op-ed articles on healthcare, the boomers, and issues of an aging society for the Scripps Howard News Service. And for seven years he was writer, producer, and host of the award winning radio feature The Longevity Report on WEVD-AM radio in New York City.