The Affordable Care Act of 2010 is one of the most impressive changes to our healthcare system since the introduction of Medicare in 1965. But Sarah Palin's "death panel" hysteria forced President Obama to remove a crucial piece of his original proposal, rendering it less effective, some might say anemic. Section 1233, which called to compensate physicians for providing counseling to patients about living wills, advance directives, and end-of-life care options, never saw the light of day.

But on July 7th, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) -- which is the largest insurer of patients at the end of life, covering 80% of those who die every year--announced that it was considering compensating physicians for having end of life conversations with their patients beginning in 2016.

To me, this proposal is a no-brainer. Six years too late in the making, this is a clear win-win for everybody in our society, patients especially.

I am an Intensive Care Unit physician and I live, work, and breathe to save patients' lives. Helping a body recover from critical illness is a privilege few can claim. It is a reason to get up in the morning.

But spend a day with me and you'll see that many of the patients I care for will never benefit from the intensive therapies I heap upon them. I could recount story after story of gruesome cardiopulmonary resuscitations which never had a chance of working, breathing tubes pumping breath after breath of air into patients who will never breathe on their own, and feeding tubes sewn into stomachs delivering artificial nutrition to those who will never enjoy another meal.

Why would I do this, you might ask? As an ICU doctor, if there is any doubt as to what the patient might choose, I err on the side of prolonging life at all costs. And there is almost always doubt, because most patients, even those with life-limiting illness, have never discussed their preferences for treatment with their doctors. And the frenzied world of the ICU is a very difficult place to do that.

Especially if doctors are not getting paid for it.

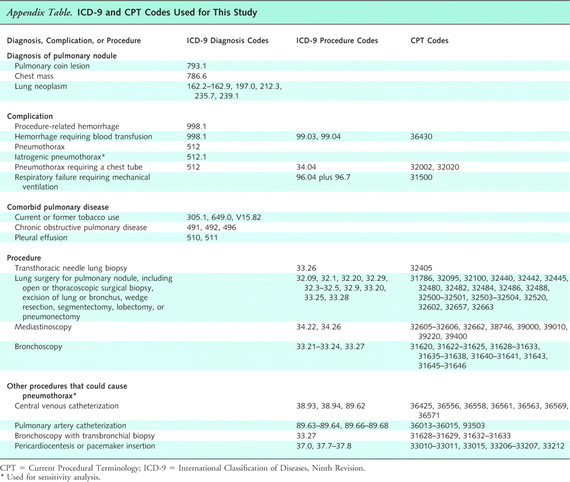

In the highly prevalent Fee-For-Service payment model of healthcare, doctors submit an itemized invoice for services rendered. Each billable activity is represented by a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code on the invoice. Each CPT code has a Relative Value Unit (RVU) assigned to it, and many hospitals report, sometimes publicly, each physicians RVU score on a periodic basis. And so in the Fee-For-Service world, a physician's value is largely determined by their billings.

Every day after work, I complete a billing form, checking off boxes for all of the treatments I administered to patients. There is a code for adjusting a breathing machine, and another for inserting a catheter into a radial artery. But there is no checkbox to demonstrate that I spent an hour, maybe two, talking to a devastated family about the grim prognosis of their unconscious loved one, and helping them decide whether or not we should insert that radial artery catheter, and continue using the breathing machine.

The other day, I took an hour out of my morning rounds to help a patient understand the reality of his metastatic cancer. He had no idea that his life would end within the next several weeks. He was shocked. He thought he had a few years at the very least. Never mind that he'd lost so much weight that his skin was hanging off of his body. He assumed that his inability to get out of bed for the past two months would resolve with more chemotherapy. No one had told him that the fast growing lung cancer, which was choking off the blood vessels in his neck and making his face puff up, was highly unlikely to respond to more chemotherapy. The news struck him like a brick. He spent the rest of our conversation with his eyes closed, responding with one-word answers, seemingly devastated. I feared that I had been too blunt, maybe dissolved all will to live. But the power of human resilience is awesome, and the next day, twenty family members flew up from San Diego at his request. With their input, he decided to refuse the highly invasive default treatments that comprise our standard attempt to prolong life--the seventh round of chemotherapy, cardiac massage if his heart were to stop, a breathing tube if breathing ceased, a feeding tube if he could no longer eat. All were considered; all rejected.

A groundbreaking report from the Institute of Medicine last year found that few patients have the opportunity to make their wishes known at the end of life, with too many deaths involving painful and ultimately unhelpful treatments.

We must compensate physicians for having these conversations with patients. And it's not just about the money. It is about the value society places on these interactions. If this time-intensive and emotionally unpredictable activity does not even merit a billing code, what message are we sending to physicians about how we want them to spend their time?

Most physicians that I know are well-intentioned. But in our desire to help, we tend towards those interventions that we have been highly trained to perform. And most physicians have not been trained to have end-of-life conversations with their patients. Adding this code to our billing sheet is likely to drive future investment, such as training and quality assessment, into this critical skill.

There is a 60-day period for public comments before a final decision is forthcoming. The National Right to Life Committee is already decrying this proposal as a threat to our right to medical treatment. Yet I can reassure them they needn't worry. Again: We ICU physicians always default to maximizing treatment unless our patients actively opt out. Indeed, this proposal would grant the public more autonomy and personal freedom, in clear alignment with the NRLC's stated principles.

This should not be a political issue, because in reality, it's a humanitarian one. Let's reward physicians for supporting patient autonomy at this most critical and vulnerable time of life.

Please submit your thoughts during this critical comment period to CMS. The link is live through September 8th, 2015 at www.regulations.gov. Click the green "submit a formal comment" button on the right side of the page and reference proposal CMS-1631-P.