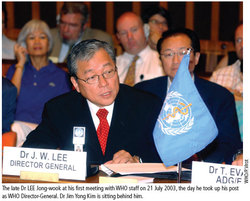

Spurred by the results, the Director-General of the World Health Organization at the time, the late Dr. JW Lee, said, "The international community's task now is to continue to work together productively to make the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine widely available to children in Africa, as lives are lost every minute to pneumococcal disease."

So, over the past 5 years, how far have we come in responding to Dr. Lee's challenge? Probably better than most would have predicted at the time, but procurement challenges and differences on pricing policies continue to vex our efforts to get vaccines to the world's neediest children.

First, let's examine what's worked well.

Financing support for pneumococcal vaccine procurement followed quickly and has exceeded all expectations. In November 2006, after an external expert review, the GAVI Board allocated $189 million for purchasing and delivering pneumococcal vaccines for children in the world's poorest countries. This was followed a few months later by a decision of the Advance Market Commitment (AMC) donors to pilot the AMC concept on pneumococcal vaccines with a commitment of $1.5 billion. These decisions were the kind of catalytic use of GAVI funds that has been a hallmark of the organization since its inception.

These decisions by GAVI and its partners in 2006 signaled to vaccine manufacturers that GAVI and its donors were serious about financing pneumococcal vaccines for poorer countries. Two manufacturers subsequently responded by submitting applications to WHO for "pre-qualification," a regulatory review that is required for procurement through UNICEF with GAVI funding. Two vaccines are now pre-qualified, a third is under review, and four companies have indicated a willingness to supply through the AMC.

The policy recommendations - and GAVI's commitment to financing - gave low-income countries the confidence to begin preparing for vaccine introduction. To date, thirty-four countries have formally expressed interest in obtaining pneumococcal vaccine through GAVI and eleven have already been approved for GAVI support. Applications and interest came from all regions of the world but the WHO regional office in Africa and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which works in Latin America, were particularly effective in supporting successful country applications.

With this momentum, high expectations were created. At the November 2006 meeting, the GAVI Board was told to expect the first doses in developing countries by the first quarter of 2008. Stakeholders, including donors and industry, were lining up to do their part.

Unfortunately, that ambition set at the 2006 GAVI Board meeting has not been met. As of March 2010, the only vaccine doses so far administered with GAVI support are those donated by Wyeth for use in two African countries, Rwanda and The Gambia. Not a single dose of vaccine has yet been purchased.

So, what's holding things up?

First, it has taken much longer than anticipated to get procurement contracts signed. Second, complex discussions related to product labeling have dragged out the pre-qualification step far longer than ever anticipated. Perhaps most importantly, inconsistencies in pricing policies between GAVI and PAHO continue to delay and complicate the process.

The first countries approved for pneumococcal vaccine were in the PAHO region. PAHO and GAVI, however, do not have the same position on tiered pricing. The revolving fund does not establish a unique price tier for the poorest countries in its region, but rather binds all countries together regardless of economic status. In short, the revolving fund principles allow a GAVI donor country like Brazil to pay the same price as a GAVI recipient country like Haïti.

The revolving fund enforces this policy through its contracts with suppliers by requiring that suppliers always give them the lowest price in the world (i.e., a "lowest price clause"). In short, if a manufacturer is already selling to a middle-income country like Brazil, Chile or Mexico at $20 per dose and then wants to sell to Haïti (or Benin) for $1 per dose, it can't do it unless it is prepared to forgo the $19 per dose in extra revenue from Brazil.

Although "work around solutions" by PAHO may permit the pneumococcal AMC to move forward, this issue remains fundamentally unresolved. Without resolution, this policy quagmire complicates the uptake of vaccines. More importantly, it risks an arrangement that leads to serial overpayment for vaccines for low-income countries in order to gain price reductions for richer countries.

The five years since the Gambia trial results were published have seen a mixture of tremendous progress and unfortunate delays. The efforts of WHO in setting policy, GAVI and AMC donors in assuring vaccine financing, and developing country governments in expressing demand and preparing for introduction have been noteworthy. The WHO African Regional Office merits special kudos for their efforts, as seven of the eleven GAVI approved countries for pneumococcal vaccine have come from the African region, where pneumococcal mortality rates are highest.

And yet, we still have not met our ambitions to deliver these vaccines to the children who urgently need them.

The main obstacles to this success are global level policy inconsistencies. Living up to the challenge set out five years ago by Dr. Lee requires that the leadership in global health and vaccines make it a 2010 priority to resolve these issues. The children of these countries and the many stakeholders doing their part deserve nothing less.