Listen, kids who die--

Maybe, now, there will be no monument for you

Except in our hearts

Maybe your bodies'll be lost in a swamp

Or a prison grave, or the potter's field,

Or the rivers where you're drowned like Leibknecht

But the day will come--

You are sure yourselves that it is coming--

When the marching feet of the masses

Will raise for you a living monument of love,

And joy, and laughter,

And black hands and white hands clasped as one,

And a song that reaches the sky--

The song of the life triumphant

Through the kids who die.-- Excerpt from "Kids Who Die" by Langston Hughes

Foreword -- Updated:

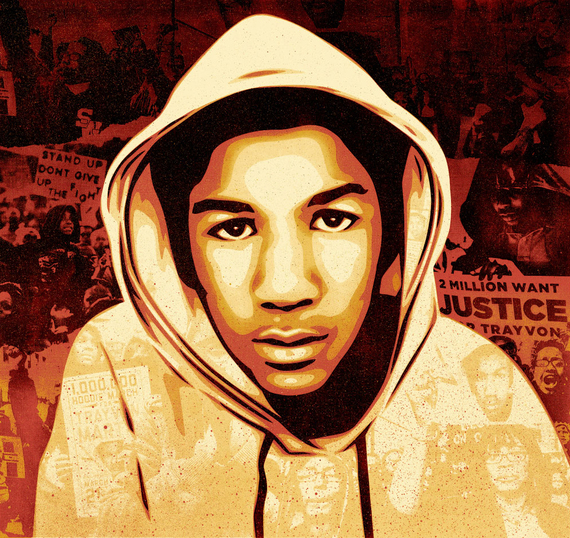

This article was written and published with my writing partner, friend and comrade Julie Smyth. its genesis lies in a conversation amongst friends after the Trayvon Martin verdict. February 26, 2016, marked four years since Trayvon's death -- which many had hoped would be a turning point in the systematic profiling and criminalization of black people -- especially young black men.

However, In a year end 2015 report titled "The Counted", The Guardian illuminated that more than 1000 young black men were killed by police in The United States. The report further stated that "black people killed were found to be twice as likely to not have a weapon". Yet even with the absence of weapons, Police Officers at the time of report were only charged (not convicted) in 18 of the more than 1000 cases.

In light of these statics, it is my assertion that "George Zimmerman's" name in the title of this essay can be substituted with that of any perpetrator of a racialized killing with the relevancy of the question remaining the same.

Introduction:

Issues relating to criminal justice have long divided The United States, creating a nearly bipolar perception of justice amongst its citizens (Alexander, 2010; Ryan, 2013). The Trayvon Martin verdict was no different -- feelings ranged from disappointment, disbelief and anger, to relief, validation, and even jubilation. But to African Americans and other racialized minorities, Trayvon Martin's death became emblematic of the extreme outcomes of racial profiling enmeshed in a history of criminal laws arbitrarily targeting Black men (Best, 2013; NeJame, 2013; Siddiqui, 2013).

The lack of consensus in the deliverance of justice, begs the following questions: what would it say about America's criminal justice system if George Zimmerman was convicted of Trayvon Martin's murder? Would justice be celebrated? Would it be viewed as a well-oiled machine that convicts the guilty and acquits those who are innocent?

While these questions are theoretical and somewhat rhetorical, this chapter aims to examine the ubiquitous correlation between Blackness and criminality in America by illuminating the criminal justice system through both historical and contemporary lenses. More specifically, this chapter investigates how legislative policies and policing disproportionately targets, and subsequently funnels poor Black men, women, and children into the criminal justice system. How did we become a society where being Black, specifically being Black and male, became criminal? This examination posits that the criminal justice system is inherently racist and therefore unjust. It further challenges Americans to utilize the loss of Trayvon Martin as a tipping point in our analysis and application of justice.

Emancipation?

In order to comprehend the "relationship between race and criminal law one must study the historic connection between defining crime, criminal law, and race. The idea that color itself can create or denote criminal behavior is deeply rooted in our history" (Finkelman, 1993, p. 2064).

The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment is hailed as a monumental achievement in ending legalized inequality and the subhuman treatment of Blacks in America. While its passage theoretically ended slavery, it also served to birth another peculiar institution -- slavery was made unconstitutional "except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted" (U.S. Const. amend. XIV).

The "Black Codes" were laws passed by Southern States in response to the Emancipation. They were intended to criminalize, and control newly freed Blacks (Alexander, 2010). W.E.B. Du Bois venomously attacked the codes as nothing more than neo-slavery (1910). Cohen (1991) states that, "the main purpose of the codes were to control the freedman" (p. 28) It became a crime to be Black and unemployed. The Codes further forbade Blacks from occupations outside those of a farmer or servant, unless they were able to pay a hefty annual tax. Laws were passed that permitted beatings, incarceration, and unpaid labor if Blacks broke what were often economic and socially oppressive contracts with Whites (Alexander, 2010; Paige & Witty, 1996). If a newly freed Black family lacked financial means, their children could be taken and placed in the unpaid apprenticeships of White businesses. 'Pig Laws' were aimed at the theft of any farm animal with a value determined at more than 10 dollars. Poor, hungry, and often homeless, Blacks arrested under 'pig laws' were often sentenced to grand larceny charges and could receive up to a five-year jail sentence. Laws were also enacted that prohibited Blacks from looking Whites in the eye, and in some states it was even a crime for a Black man to walk on the same side of the road as a White person. Finally, it was also against the law for a Black person to testify during any court proceedings involving Whites (Finkelman, 2003; Muhammad, 2010).

These laws created a boom in the prison population. Once arrested and convicted, the formerly freed Blacks were leased out by the criminal justice system to labor in coal mines, railroads, and of course, plantations. This 'convict leasing system' allowed states to lease out their mostly Black prison population as laborers for a fee, which became popular and profitable for both states and businesses throughout the South (Alexander, 2010; Mancini, 1996; Oshinksy, 2008).

For such a clearly prejudiced system to flourish in light of the Emancipation, the public had to also buy into the criminality and inferiority of Blacks (Alexander, 2010). As such, the images and narratives told of Blacks pre-Emancipation were generally that of a trusting, submissive and docile people. The term quashee was used by White slave owners to describe Black men as, "gay, happy-go-lucky, frivolous and cheerful" (Beckles, 1996, p.9). White supremacy and the institution of slavery were further rooted in this attributed identity.

Post-Emancipation, the attributed identity of Blacks in America shifted. Social scientists, who long theorized Black inferiority during the heydays of slavery, were galvanized to observe and quantify the behavior of freed Blacks. Hoffman's landmark 1896 publication, Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, saturated public consciousness with the imagery of Black men as criminal. His research negated the proximity of slavery to its subjects, negated the present social and economic plight of Blacks, but nonetheless proclaimed that, "crime, pauperism, and sexual immorality" (p. 217) are tendencies of Black people. Proponents of this doctrine could then substantiate their belief by highlighting the prevalence of Black Men in the criminal justice system.

The colored criminal does not as a rule enjoy the racial anonymity which cloaks the offenses of individuals of the white race. The press is almost certain to brand him, and the more revolting his crime proves to be the more likely it is that his race will be advertised. In setting the hallmark of his color upon him, his individuality is in a sense submerged, and instead of a mere thief, robber, or murderer, he becomes a representative of his race, which is in turn made to suffer for his sins (Sellin, 1928, p.63).

If you have enjoyed reading thus far? The article in its entirety can be found here