Ever gotten into a debate about religion on the Internet? Then you know that religion is hard to talk about objectively. It brings out people's strongest and most stubborn opinions. And everyone does have an opinion. Maybe you think religion is a tool the powerful use to control society. Or it's a personal relationship with Jesus. Or it's just primitive superstitions passed down via Gideon Bibles - whoever the Gideons are. But what if religion weren't just a matter of opinion?

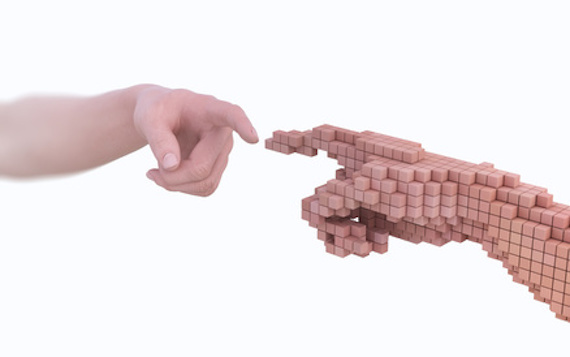

What if we could objectively figure out which ideas about religion - not about God, but about human phenomena like ritual and religious belief - were true, and which weren't? As it happens, there's a whole field of human endeavor dedicated to figuring out which of our ideas is true: science. With the scientific approach, we can produce hypotheses and test them. We can establish theories. And we can build models - both physical and virtual - and compare their behavior with the real world.

This last method - modeling - is becoming a tool of choice across many fields. Economists use simulations to predict shifts in markets, while climatologists model climate change. Now, the scientific study of religion and culture is catching up. I'm a postdoc at the Institute for the Bio-Cultural Study of Religion (IBCSR) in Boston. Together with the Virginia Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation Center (VMASC) in Virginia, we're embarking on a new, multiyear project: building computer models that simulate how religion affects society and individuals.

The Modeling Religion Project is pretty big.* We've got burly computers and some of the world's top experts in modeling and simulation. We've got anthropologists and experts in religion. The goal is to determine whether we can recreate historical events, learn about religious violence and terrorism, and understand religion's role in transitions from preagricultural to industrial societies.

What's modeling good for?

Scientific models are especially useful for subjects that don't lend themselves to tidy experiments. Take climate change. It'd be really tough to run experiments on the earth's atmosphere. There'd be no control condition. And getting the study design past your ethics board would be a nightmare. Computerized models solve these problems - if you want to determine just how many years Miami has before it becomes an underwater theme park, you program the variables into your model, run ten thousand simulations, and see what the average result is.**

Religion's role in society is another arena where controlled experiments are a really tall order. You can't round up 100,000 random people, assign half to atheism and half to Islam, and see what happens. (Again, the ethics board would have a field day with this.) So models are a promising way of testing naturalistic hypotheses about religion, society, and cognition. But so far, that promise has gone mostly unrealized - only a few researchers have tried to build computer simulations of religion. IBCSR and our partners at VMASC will be blazing a new trail through the scientific wilderness.

What does it even mean to "model religion?" Are you guys trying to find God in the computer?

Let me stress it again: we're not testing the metaphysical or spiritual claims. We won't be modeling whether Jesus rose from the dead or not, or whether Vishnu created the universe while floating on Shesha the sea-snake. We're not dealing with those questions. (At least not while we're on the clock.) Instead, we're testing social, cognitive, and evolutionary theories about why humans do religious things and believe in religious ideas.

All around the world, human cultures invest enormous amounts of time, money, and energy in religion. Cathedrals, mosques, temples, innumerable hours spent on religious ritual - from a purely naturalistic perspective, religion is a puzzle. Why would homo sapiens devote so much time and energy to activities with no obvious purpose, referencing concepts that can't be proved?

Some researchers postulate that religion is an evolutionary byproduct of cognitive adaptations, like our need to keep track of other people's minds. Evolved for group living, we're always on the lookout for intentions and purposes in our environment. But only people and animals act with intentions. A rockslide doesn't choose to slide: it's just a physical event. Even so, our purpose-seeking brains might "invent" a spirit or god that caused the rockslide. Maybe this cognitive hiccup is the origin of religion.

Others suggest that religious ritual is a binding agent for human society, unifying tribes so that they can provide for their members and compete effectively against other groups. This hypothesis might sound warm and fuzzy. Sure, a religion that brings everyone together might help a tribe or nation to succeed. But in a competitive, evolutionary world, success for one group often means failure and death for another. So religion might be the human equivalent of claws and teeth: a powerful tool that helps us survive, at the expense of others. Not the best foundation for building a moral case for religion!

Other theories abound. Terror Management Theory (TMT) posits that humans create imaginary worlds in order to escape the fear of death. Anthropologists argue that religious rituals are similar to animal signals, conveying social information. And sacred values theory models religious terrorism in economic terms.

Our team is testing all these theories and more.

Great, you might be thinking. Except you still haven't described how computer simulations will actually test these theories.

Guilty as charged. Fortunately, this post is just the first in a series. I'll be regularly updating readers about this project, giving a first-person window our lab and work around the world - from Virginia and Vancouver to the Czech Republic and central Turkey. Next time, I'll describe the different types of computer simulations we'll be using. When it's all finished, those Thanksgiving dinner-table debates about religion are about to get a lot more interesting.

________

* You can tell I'm a Midwesterner because I use mitigating phrases like "pretty big" when I mean "huge."

** And then, after watching the Florida legislature ignore your work, possibly develop a drinking habit.