Reflecting on my career in the field of HIV prevention, care, and treatment, I often think about the quest for a safe and effective HIV vaccine. This year on HIV Vaccine Awareness Day there's more reason than ever to celebrate. An ideal HIV vaccine would provide a cost-effective HIV prevention strategy that would have a easier access and adherence for many people than other prevention interventions while also providing long-term protection. And science is bringing us closer to that possibility.

When a person is infected with HIV, the virus uses one of its unique advantages to hide from the immune system while also attacking it. During the earlier phases of infection billions of new copies of the virus are being made in the body. Eventually, the body's natural defenses kick in and began to get a handle on containing the virus. However, they are never able to defeat it. And as this long war is raged more and more of the body's defenses are destroyed. To this day, researchers have never found someone whose natural immune system has been able to defeat HIV completely.

Researchers have hoped that by giving the body instruction early -- before it encounters HIV -- it would be able to achieve finally something we've never seen before, a human immune system definitively beating HIV. The way to do that is with a vaccine. Vaccines work by providing the body with tools that will help teach it how to fight a disease before it encounters that disease. An effective HIV vaccine would teach our bodies to react to HIV with more than its basic immune response. It sounds simple, but this continues to be a major challenge for science.

The good news is the pursuit of an HIV vaccine has taught researchers more than ever; new breakthroughs represent some of the most cutting-edge developments in the study of the immune system.

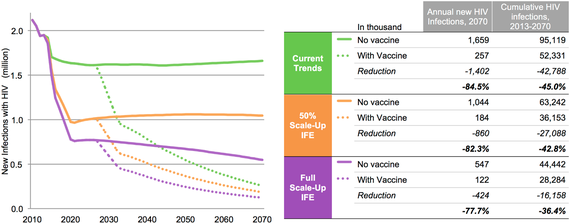

ln recent years several amazing scientific advances have introduced new tools to help up better control the epidemic. With the right deployment, education, and buy-in there is a chance to change the course of the epidemic and finally break its stronghold on our communities. The chart below shows the impact of these new tools on the epidemic and the impact a safe and effective vaccine with the right deployment, education, and buy-in could add to current tools.

The model looked at three possible scenarios:

Exploring the Impact of and Requirements for Adding a Vaccine to the Updated UNAIDS Investment Framework to End AIDS (IFE)

Current trends - assumes that incremental linear scale-up of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission from 2010 to 2013 continues, off-setting the natural increase in new infections due to population growth and resulting in a steady annual incidence; eligibility for ART remains at < 350 cells/mm3 and ART coverage is capped at 80 percent. (Current WHO guidelines call for treatment for everyone with HIV regardless of CD4 count, but this has not yet been implemented in many countries.)

50 percent scale-up of IFE - assumes that UNAIDS IFE targets are only achieved halfway, based on linear scale-up from 2013 coverage to 50 percent of IFE target levels in 2020.

Full scale-up of IFE - assumes that the IFE targets are fully achieved, based on linear scale-up from 2013 to the target levels in 2020.

We need a vaccine to help break the back of the HIV epidemic. But the search has been long and hard. In fact, nothing about responding to this virus has ever been easy. HIV has challenged our understanding of medicine, of the ways the body reacts to diseases, of how to make and test drugs, of the politics of the way governments, respond to a pandemic, of the way public health systems respond to a new disease, of the we talk about and have sex, and of community advocacy for systemic change. The legacy of HIV continues to cast its long shadow across our lives and the span of time. As new champions rise to join us and continue this fight to end the epidemic, I am more excited than ever about the future of HIV prevention.

This year we may finally see the start of a new large-scale trial building on the 2009 results of RV144, a large-scale vaccine study in Thailand that provided the first proof of concept that an HIV vaccine could work. Although the overall trial results were a modest 32 percent efficacy, for a period after vaccination the protection level was much higher, peaking at around 60 percent. Based on these results, the global scientific HIV vaccine community has spent the last several years looking at ways to improve and maintain that higher level of efficacy. Now we hope to head into a follow-up trial in South Africa with a vaccine strategy based on the one tested RV144, but tweaked in a way researchers hope will provide more protection and localized for the subtype of the virus most common in Southern Africa.

And we may also see another, completely different, vaccine strategy heading into the field in the coming months, looking at a different approach which has shown some initial promise. This "mosaic" vaccine is designed to protect against many different subtypes of HIV, making it a potential global vaccine for HIV. This vaccine was developed by the pharmaceutical company Janssen and would be tested through a large collaborative undertaking with multiple research networks working together with a major pharmaceutical company. We haven't seen this level of industry commitment since Merck and the Step trial in the early 2000s. I'm excited to see how a partnership among industry, governments and civil society could work together to develop a vaccine for the masses.

Finally, this year we saw the start of a new trial exploring using a natural component of the immune system response -- the antibodies that develop after someone is infected with HIV to fight the virus. The antibody response in HIV-infected people is too little and too late to effectively fight off the virus. But researchers are exploring using these antibodies for HIV treatment, prevention, and a cure. In prevention research, the AMP study (short for antibody-mediated prevention) is looking at giving HIV-negative people infusions, or drips, that contain a broadly neutralizing antibody,. Researchers hope potential powerful new strategy will provide answers on how to develop a better HIV vaccine -- one that could teach the bodies of HIV-negative people to develop this potent bNabs in time to protect them from HIV infection.

Even as the world slowly begins to embrace PrEP as a prevention option, and as more people around the world gain access to PrEP, we still have hope and need for a vaccine. A strategy that could only require a few shots rather than daily medication. Vaccines have been some of most cost effective strategies and been an essential part of eliminate disease like small pox and polio,If this epidemic has taught us anything, it is that we need multiple ways to fight the virus. Giving people options that fit into that lives and they way they live so that HIV does not have be a worried for them no matter how they encounter it. So when we critically examine how we might reach those whose complex lives have made it harder for them to use existing HIV prevention strategies, we owe it to them to establish a battery of additional options, including a vaccine.