Louis Sullivan, father of the American skyscraper, posed the definitive question about that new architectural form back in 1896: "What is the chief characteristic of the tall office building?" he asked in an essay titled "The Tall Building Artfully Considered."

His answer - that it is "lofty" - is a classic. The implication is that a tall office building must be, as Merriam-Webster defines the word, "very high and good, and meant to be admired."

In Raleigh, most of the tall buildings in our skyline struggle mightily to achieve a lofty status. The distinct exception is Wake County's Akins Building between Salisbury and Fayetteville streets, a stepped-back, limestone-clad Art Moderne gem. It was designed by Luther Lashmit in the early 1940s to house an insurance firm; today it's home to county offices.

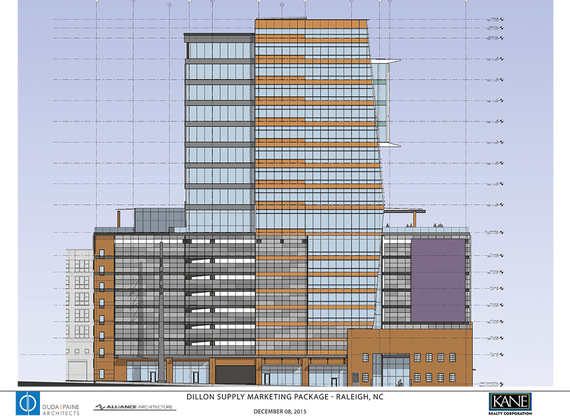

Now comes a 17-story, mixed-use building for Raleigh's warehouse district, designed by the Durham firm of Duda Paine for developer John Kane of Kane Realty. It will symbolize Raleigh's return to downtown, as millennials flock here to mingle their work and play in an urban environment. Significantly taller than surrounding structures, including the four-story Citrix office building a block to its northwest, the new tower will usher in a new era of building up, rather than out, for Raleigh.

"For better or worse, land costs in downtown Raleigh have increased significantly," says Steve Schuster, chair of Raleigh's planning commission. "To redevelop downtown, the private sector has no choice but to go higher."

This new building raises the bar for the loftiness of the architecture that comes after it. Duda Paine is well-known for tall buildings in cities across the nation and especially the South - including Charlotte, Atlanta, and Austin and Fort Worth, Texas. The firm's work is respectful, solidly grounded in the modern aesthetic and known for a layered - rather than monolithic - approach to design.

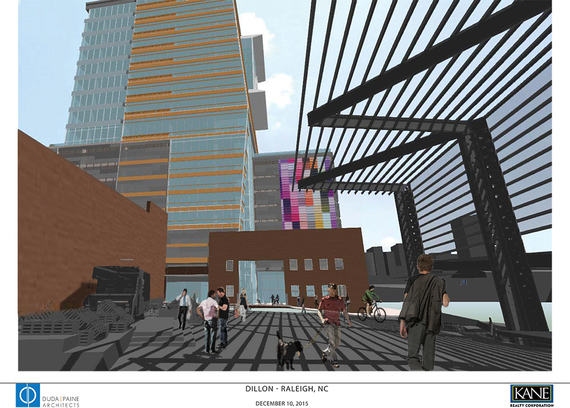

Here, the architects looked back to architectural historian Colin Rowe's 1978 book, "Collage City," for inspiration. In it, the author suggested that buildings in the urban environment can create more vibrant experiences if they layer smaller designs into a whole. "That's our strategy," says Turan Duda, project architect and partner at the firm. "You take a block and split it - carve it and shape it to break the scale down to make it look like a collection of buildings."

Duda turned too to the late Charles Sheeler, a 20th-century American modern artist and photographer - also a fan of layering, but for a richer artistic experience. "The question is how to see this building not just for the first time, but the second, third, fourth, and fifth time," Duda says. "This building has an idiosyncrasy that requires a deeper look - to see something new each time you see it."

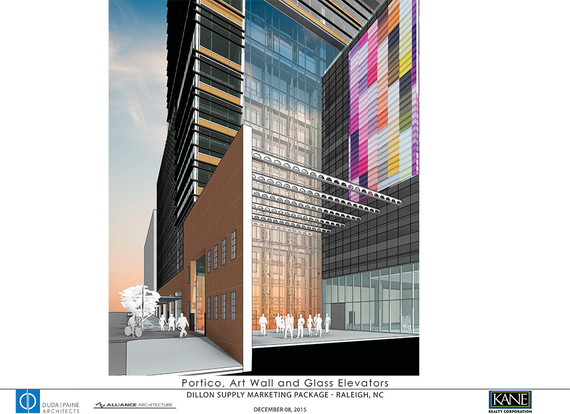

The new tower, on the site of the Dillon Supply building on West Martin between South Harrington and South West streets, takes its ground-level cues from its surroundings. Its physical relationship to the Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) across Martin Street is acknowledged with an opening in its facade, opposite CAM's distinctive entry canopy. There's also a five-story-tall multimedia wall to announce CAM exhibitions and others in a district known for the arts.

A pocket park and vestibule, carved 40 feet by 60 feet into its southwest corner, addresses a new civic plaza across West Street, adjacent to the four-level Union Station designed by Raleigh's Clearscapes. Along its pedestrian level, 25,000 square feet are reserved for restaurants and retail space - with expanded sidewalks.

Its podium - a seven-story parking deck, its 980 spaces to be shared with the city and Union Station - will be a base for 10 more levels of offices. On its ninth floor, a sky lobby and an indoor-outdoor restaurant with terrace will open to views of the city. Four stories above the terrace, a monumental, iconic and four-level "sky window" will be inserted into a gently sloping, southern facade.

But like the Akins building before it, the most memorable aspect will be the deliberate setback of its tower. Earlier concepts indicated a volume that was massed straight up from the street, to which some critics objected as out of place in the low-lying warehouse district, but that's been scaled back. "We brought the narrow end of the building to the street and the tall part back," Duda says. "It's a very conscious decision on our part - it gives an elegance to the building and pushes the massive parts back, so you're not experiencing them at the street level."

At ground level, it's to be clad in brick like its neighbors, with some of the building's original steel beams re-purposed to cover the pocket park and vestibule. Above, layers of glass, black steel, and gray and terra cotta-toned metal panels will emphasize the building's vertical and horizontal planes. These materials will be grouped together to create some visual forms, or broken apart to dilute others. As the sunlight hits the facade, textured patterns in the building's skin will be exposed.

All these disparate pieces, the architects say, are intended to add up to a greater whole. From a distance, the building will assume an iconic presence in the warehouse district. Up close, it's about place-making - on the ground and out on the ninth floor terrace, too.

It's also a 21st-century precedent for the buildings that follow in downtown Raleigh. That begins with an adjacent eight-story residential component that will front Hargett Street. But there are others on the radar too - some that will extend east toward the tall buildings of Fayetteville Street.

"When you look at the selling price of the property at Dawson and Hillsborough streets across from Campbell Law School - the city put it on the market at $3 million and it sold at $6.3 million - clearly there will be a tall building on that site," says Schuster, the planning commission chair. "And The N&O building - the developers paid a handsome sum for that site - there's a need for a taller building there too."

The challenge now is for future tall buildings to live up to the promise of Duda Paine's lofty design of the new Dillon building, scheduled for completion in 2017.

That's a worthwhile goal for every developer in Raleigh.

J. Michael Welton writes about architecture, art and design for national and international publications, and is architecture critic for The News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C., where this column first appeared. He edits a digital design magazine at www.architectsandartisans.com and is the author of "Drawing from Practice: Architects and the Meaning of Freehand" (Routledge: 2015). He can be reached at mike@architectsandartisans.com.