Montana Avenue in Billings is a startlingly urban raft on the vast, grassy sea of rural southern Montana. It has microbreweries, artists, a cowboy hat-fixing genius, solar-powered lofts, and huge summer street events, along with homeless people, addicts, and the occasional break-in or fatal stabbing in an alley.

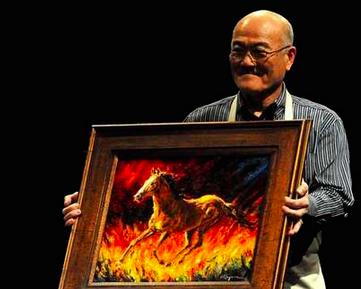

Saucer-size rodeo buckles, business suits, elaborate mustaches, and sleeve tattoos co-exist. Shop doors stand open on summer evenings, when the draw of Harry Koyama's narrow gallery strengthens to an irresistible force. Harry himself is the lure, as much as his flamboyant canvases of wildlife, wild places, and the vivid people who populate southern Montana. His presence pulls in locals who normally wouldn't think of buying original art.

"You end up doing a lot of explaining," Harry says, hands on knees on a straight-backed chair in the small studio behind his shopfront, having given a visitor the comfortable sofa that dominates the space. "Most people have some kind of enjoyment of art whether they know it or not." In his 60s now, Harry came to painting late, after 35 years farming east of Billings. His hands are smooth but still bear the signs of rough work. He is slight and brown, with thinning hair and a face that falls into smiling lines even when he isn't smiling.

In this place, Harry is an unlikelihood. Although ethnically Japanese, he has lived a classically Montanan life. His father, Tom, was born in Sheridan, Wyoming, the son of railroad immigrants from Wakayama, Japan, who established a farm south of Hardin, Montana. Harry was born and raised in Hardin (current population a bit over 3,500) with seven brothers and sisters.

He earned a fine arts degree and kept his creativity alive doing commissioned metal art -- a popular local form -- in winter. After a triumphant struggle with cancer in the '90s, Harry returned to his boyhood love of painting. Collectors responded so passionately that by 2003, he was able to paint full-time. Now his pieces go around the world, including to the US Ambassador's residence in Beijing, where one of Harry's massive bison watches over Ambassador Baucus.

As history has a way of doing, World War II intervened in this pastoral American story. Tom Koyama left for California shortly before the war broke out and married Emiko Kubo there in 1942. The War Relocation Authority arrested the pair on their honeymoon and shipped them to the Gila River War Relocation Center southeast of Phoenix, Arizona. Friends in Montana intervened and secured the Koyamas' early release by insisting that the war effort required Tom's expertise at bringing in the sugar beet harvest -- but not before Harry's eldest sister was born in camp.

Although Tom and Emiko never spoke bitterly of their imprisonment, they had camp friends who did so the rest of their lives, Harry recalls. His boyhood in the prosperous postwar years was distant from the experience of his parents and grandparents, but there were poignant moments. One of his art professors, Ben Steele, was a survivor of the Bataan Death March who struggled to put the past aside when a young Japanese American named Harry walked into his class in the 1960s. "I never knew until years later," Harry says of his old friend Ben, who welcomed the younger man to their Billings artists' group when Harry moved to town in '07.

As one of very few Asian Americans in the area, Harry occupied a middle ground between the white ranching community and the Crow Indians whose reservation borders Hardin. Today his art also occupies that middle ground. He paints Crow tribal members in full powwow regalia, as well as ranchland that has since been strip-mined for coal. His paintings often come with a story. "This is on so-and-so's place," he'll tell a visitor, or "I saw that pheasant up Sarpy Creek a few years ago." Relentlessly, the work calls out to the place.

Most of the year, Montana presents a nearly monochromatic landscape: white in winter, brown in summer, with a bright green moment in late spring. Raised on that sober palette, Harry Koyama is wanton in his use of color. His bears are red. His bison glow golden. "Color is my own enthusiasm with the profession and the medium," he says. "Being able to express yourself with color is why I get into the vibrancy."

The animals are more lively and real for the impossible shades that represent them, because Montana's wildlife is surreal, bigger than life, impossible to believe when you see it for the first time. The color evokes the awestruck feeling of those encounters. Encountering Harry, surrounded by these canvases, is a similar experience, a flash of brilliance on a quiet day, a busy street at the heart of a place he holds in the palm of his hand and offers, without bitterness.

Note: This post first appeared on Public Streets, a biweekly urban observations series curated by Ellis Avery at publicbooks.org. Reposted with permission.