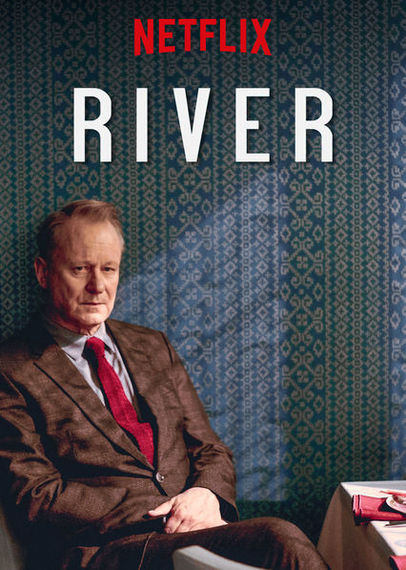

Detective Inspector John River -- magnificently played by acting legend Stellan Skarsgard -- is a brilliant detective with a troubled past that often seeps into his present, especially as he's haunted by the murder of his partner Detective Sergeant Jackie "Stevie" Stevenson under increasingly suspicious circumstances. Set with the backdrop of an immigrant-heavy London, DI River tries to uncover his partner's killer while hiding the truth of his undiagnosed mental illness, one that causes him to hear and see things that aren't there among several other choice personality traits.

Netflix's River shies away from the details of a prognosis, but along with the ghosts DI River sees and talks to, he's photosensitive, and when the situation requires it he radiates an immense empathy that makes him a brilliant interrogator, if anti-social and introverted in his personal life. In many ways, he reminds me of Bryan Fuller's version of Will Graham in the Hannibal reboot: such a huge amount of empathy that borders on insanity when not carefully kept in check, and a whole hell of a lot of personal and unresolved trauma that's a septic festering emotional wound. As it turns out, these aren't actual ghosts River sees, but rather the projections -- the "manifestations" as he calls them -- of his hopes, fears, desires, and regrets. Like so many of us even without this kind of mental illness, he sees what he wants to see.

To further complicate matters, the displacement of immigration, both internal and external, plays a huge role in not just River's life, but in virtually every character in this highly-nuanced six-episode miniseries.

River's mom abandoned him as a child and his grandmother was abusive -- both presumably because of his illness. After his grandmother's death he immigrated from Sweden to London at 14 to live with the mom who gave him up, who had no change of heart about her decision in the years since. So an already-struggling internally young River was forced to negotiate life as a different kind of outsider in a hostile new city. London is "a city for everyone who belongs everywhere else," says River, a man who hates the place and yet somehow was too entangled in its web to leave.

River's dead partner Stevie comes from a huge Irish family who moved to London during a time when signs around the city read: "No Irish, No Coloureds." Both River and Stevie embody the phenomenon known as "invisible immigrants" -- people who share physical traits with majority citizens of their new home, but who aren't actually one of them. River's new partner Ira King is half Muslim, half Jewish -- "I'm the original Gaza Strip," Ira quips -- who also negotiates a complicated cultural identity. Further, the men at the kebab shop that plays a large role in Stevie's murder investigation are all immigrants and refugees from the Middle East and Africa, and the theme of trafficked women from Eastern Europe also enters into the mystery of who killed Stevie.

A quote by one of River's visions, a Somali professor-turned-kebab-shop-worker Haider, sums up the immigrant experience in a nutshell: "We come to this country so filled with hope, so grateful for the potential. Yet still they say, 'Why do we leave our door blindly open to these people?' But you migrated here, too. You see what people here do not see. You of all people. If only you had seen me as clearly as I see you. Seen the loneliness. The isolation. What it is like to be so far from your country and family. what it is like to try and fit here. How hard it is just to be."

Immigration doesn't only externally displace a person from familiar surroundings, language, and culture, it also internally displaces us into a cultural and linguistic limbo that at times can be a horror to navigate. Lives become split into befores and afters, and even if you inhabit a closely-knit immigrant community, immigration forces us into liminal existences often on the social and cultural margins that create perceived differences between us and them, and even causes ruptures between us and the homeland that grow more and more apparent the longer one lives outside.

None of this is to say that immigration and mental illness go hand in hand, although immigrants do tend to be stigmatized in many of the same ways as people with mental illness through ostracism, stereotyping, and even actual physical violence due to perceived or marked difference. And through the stories of London's immigrants, as well as River's own struggle to accept his internal displacement from mental health, River shows everyone's conflict with just being in our modern world, where movement is the new stability, and change is the only constant.

Who knew that it would be modest little online streaming service and DVD rental business Netflix that would end up pushing so many social boundaries and taboos out into the open in such meaningful ways? And who knew that some of the few three-dimensional female characters in recent years would also feature in their plan of smashing taboos? One of River's main nuanced women -- in a deliciously ironic presentation -- is an actual ghost, whose depth emerges as each episode goes on.

Where The Leftovers critically examined life after trauma, and Jessica Jones illuminated the insidious process of domestic violence and abuse, River unpacks the nuances of not only life with a mental illness, but how those around it are, too, affected in positive and negative ways.

While everyone gets to a point in life where they are haunted, only few have the opportunity to see these hauntings manifest in a pseudo-physical form. Watching River often physically grapple with his demons and his mistakes is not only a marvelous opportunity for one of Stellan Skarsgaard's most unique and powerful performances, but also a chance to visualize what our internal dialogues would look if the people that haunted us actually manifested.

For River, love -- not just being loved, but admitting to love -- ends up being the roundabout answer to the start of his own healing. For others the answer is medication, or therapy, or exercise, nutrition, or any number of hundreds of combinations of things to help you regain your own physical and mental autonomy. Sometimes, simply admitting you're powerless is the first step to reclaiming that original power we all were born with that may get stolen, taken, tortured away from us through other people's bad decisions, unfortunate events, or our own faulty brain chemistry. None of this is easy. At the same time, none of this is impossible.

What contributes to the challenge is the fact that mental illness is not considered socially acceptable. Brain cancer we can talk about, tumors, aneurysms, clots, are all discussable. And there's no shame involved. But illnesses of the mind, of our thinking, whether innate or created through abuse and trauma like DI John River, are just as insidious as the cancer that invades our cells. The brain is as much an organ as any other, so why this arbitrary stigma surrounding mental illness? Why do we hold a Dark Ages belief in a time of such marvelous technological development?

"Madness can bring its own kind of clarity," says River. And so too can the immigrant experience bring clarity as it shows us how tolerant our society is or isn't. It challenges our stereotypes. It forces us to transcend the boundaries of our own socio-cultural perceptions, as well as our very own perception of self, whether we're internally/externally displaced or not. With the Brexit in the UK and rise of Trumpism in the US, it's more important now than ever to embrace diversity in all its forms before we begin repeating some of modern history's darkest days.