After managing to catch the final days of this exhibition, this is what I thought...

Stepping through the double French doors of 3 Howard Street in New York's bustling Chinatown will immediately vitalize your day - visually and intellectually. The exhibition on show, Hunger is the Best Sauce, is The Still House Group's co-founder, Isaac Brest's most recent provocation of the city's thriving art scene. The show effectively presents a new take on some of the most important works from the past century, while casually digging into the ribs of the white-walled sterility of Chelsea's galleries.

Isaac Brest, I hear this is the white they use at David Zwirner, 2015

The front room of the exhibition holds the installation: I hear this is the white they use at David Zwirner, 2015. Interrupting the meticulously installed, vibrant yellow panes of fiberglass sheathing, an emblem of the modern era's progressive urban development, three framed panels of stark gallery wall remain. They hover, absent of the noisy commercial branding and design, entirely relieved of their conventional function-- to bear the art object. Through the black PVC vinyl strip door, the back room contains another installation: Early Retirement (Subprime), 2015. Assorted arrangements of abstract paintings are forged by Brest's decision to abstain from painting. These five works reveal the hidden truth entombed behind the white paint of the gallery walls, extracting a functional composition never intended to be viewed, let alone appreciated. In this Contemporary marriage of Dadaist theory and Minimalist aesthetic, the viewer is left to contemplate the factory-green sheets of drywall, installed and preserved before their fated concealment, as completely perceptible works of art. In both of these rooms, there is a resonance of Brest's strong engagement with the Minimalist artists of the sixties and seventies, such as Ellsworth Kelly and Blinky Palermo, and even as early as Robert Rauschenberg's White Paintings from the start of the fifties. Yet in these two rooms, Brest has confronted their works boldly. He has taken one step further and he has removed the canvas entirely.

Isaac Brest, Early Retirement (Subprime), 2015

Recall the unwieldy titled 1958 exhibition by Yves Klein: La spécialisation de la sensibilité à l'état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée: Le Vide (The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility: The Void). With this radical embrace of nominally empty space, the artist proposed that the aura he emitted as he stood in this bare gallery space was artwork enough. In this first prominent engagement with the immaterial artwork, the prevailing notion around Klein's 1958 show remains one of absence rather than abundance.

Challenged further in Robert Barry's 1969 exhibition Closed Gallery Piece, the notion extends further to voiding physical access as well as physical content. A year later, American Installation artist, Robert Irwin took a different conceptual approach to the same issue with his LA show Experimental Situation by visiting the gallery every day for a month filling the space only with his artistic contemplation. The process of Irwin's creative thought becoming the final product of a show evokes a similar reaction to the 3 Howard Street's 'early retirement': a conceptual and spiritual gesture that becomes almost tangible.

However, pushing the envelope further, it is the amalgamation of ideas from Los Angeles conceptual artist, Michael Asher and Irish artist and critic, Brian O'Doherty that really makes entering this small Still House Group outpost most refreshing. Within a couple of years of one another, Asher and O'Doherty uniquely challenged the spatial context of the white-walled gallery in shaping our understanding of art given the effect it had on the relationship established between the viewing subject and the viewed object. Most prominently in Asher's 1974 exhibition at the Claire S. Copley Gallery in Los Angeles, the artist removed the partition wall that separated the gallery's back office space from the exhibition space, exposing their 'back of house' business operations as one with the designated gallery space. Similarly in his celebrated set of essays, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, Brian O'Doherty delves deep into the numerous effects that the new style of clinical galleries have on the works of art they hold.

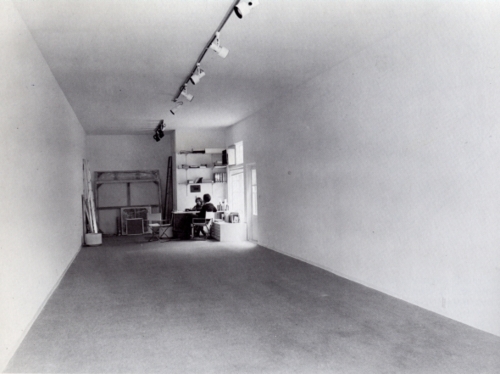

Michael Asher, Untitled, 1974, Claire S. Copley Gallery

"The wall becomes a membrane through which esthetic and commercial values osmotically exchange. As this molecular shudder in the white walls becomes perceptible, there is a further inversion of context. The walls assimilate; the art discharges. How much can the art do without?"

Brian O'Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, p. 79

In Hunger is the Best Sauce, the Chelsea-style white walls of the front room installation indulge our inquisition into how exactly we can categorize what we are observing. The commercially branded, vivid yellow fiberglass sheathing of the 'gallery walls' both add to our understanding and to our confusion of the 'gallery space - gallery wall - work of art' relationship that Brest has daringly provided to us. The back room (and an adjoining side room that contains four types of specialty drywall, some American, some European, are framed in their original state) adds yet another direction for us to consider in this difficult conception. The space ties the philosophies of Klein, Barry and Irwin together, while at the same time presenting us with the notion that the industrially-colored drywall beneath - where works once were hung - could maybe, possibly, perhaps be the works of art themselves?