It is no simple feat to make a person disappear. The city of Los Angeles, along with members of my family, spent the better part of a century falling into what historians refer to as the nostalgia trap, an unintentional erasing of the less proud elements of the past, the gradual non-existence of entire people and events. In the late 1920s, the Julian Petroleum Corporation, though scarcely remembered today, defrauded some 40,000 investors of $150 million in one of the nation's earliest Ponzi schemes, driving Southern Californians to the brink of revolution as they witnessed their most trusted leaders and institutions caught in the meshes of the scandal's net. As the 85th anniversary of the Julian Petroleum trial passes unnoticed, my family mourns a different collapse. We mourn the financial and moral unraveling of my great-grandfather, Frank Keaton, a Julian Petroleum investor who sought to provide a better life for his family but in the process lost more than just his life's savings. He lost his mind.

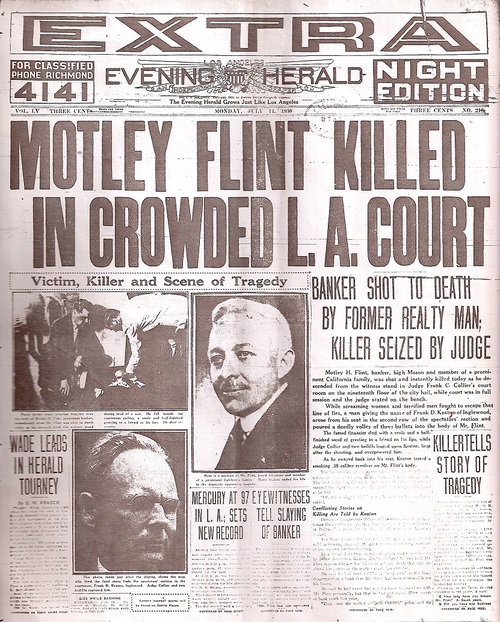

On July 14, 1930, in the chilly air of Judge Frank C. Collier's courtroom in Los Angeles City Hall, a crowd huddled around two men lying face-first on the ground. The first man, my great-grandfather, squirmed as men in uniform searched his belongings, examining the sundries of an onerous life. From his pockets came a lonely dime, a pack of cigarettes, a tattered pamphlet; from the crown of his head, an imitation Panama hat, its crummy fabric tormented by the summer heat and stained with sweat.

There wasn't a person assembled who didn't recognize the second man, Motley Flint, a Hollywood banker once celebrated as "one of the most widely known men in Los Angeles." His pockets produced $63,000 in cash and checks and a diamond-studded cigarette case; the elegant Panama hat atop his head confessed a life of prestige and privilege, intricately woven from the straw of the Ecuadorian toquilla plant, a pristine white. And now stained with blood.

Earlier that morning, Frank Keaton entered Department 39 in downtown L.A. as a civil case was in progress. The ongoing trial was between legendary film producer David O. Selznick and First National Bank concerning stock that Selznick used as security for a loan years earlier. Frank quietly took a seat in the second row of the spectator section and watched as Motley Flint, a former officer of First National, stood on the witness stand, struggling to recall details of transactions between Selznick and the bank which took place under his watch.

Frank dozed in and out of Flint's testimony, enjoying the coolness of the courtroom and a respite from the record 97-degree heat outside. Unable to sleep the night before, Frank spent hours seated in the living room of his Hawthorne home, brooding, wearing a blank look on his face as he stared out his window at nothing in particular.

As Flint carried on, Frank became overwhelmed by a sharp buzzing in his head. His mind went black, filled with thoughts of trouble at home: his recent financial ruin, his impending foreclosure, his wife's ongoing medical problems. "It looked like a whirlwind came over," Frank recalled. "It got dark and gloomy." He heard voices screaming in his head. Old radio broadcasts pounded against his temples, shouting Motley Flint's name as among the men who could have prevented the Julian Petroleum crash and saved the fortunes of thousands of investors.

Flint finished his testimony and received permission to step down from the stand. As he made his way to the spectator section, Frank bounced to his feet and used his Panama hat to conceal an antique .38 Smith and Wesson revolver purchased in Chicago decades earlier. Three bullets exploded from its barrel. The first shot struck Flint's neck, stopping in his collarbone; the second punctured his heart; the last, his lung and liver.

Motley Flint, a complete stranger to the man brandishing the gun, dropped dead without so much as a groan. Frank threw the revolver at Flint's corpse and collapsed into his seat. "He ruined me! Oh my God, I can't believe I did it," my great-grandfather repeated to himself, burying his face in his hands as Judge Collier came barreling from behind his bench to restrain him. "I can't believe I did it."

For decades, businessmen, politicians, and celebrities alike championed Motley Flint as the poster boy for the ever-expanding city of L.A., particularly the burgeoning movie industry in Hollywood. Flint counted Jack and Sam Warner among his closest friends, and the brothers claimed that without his moral and financial support, Warner Brothers Studios would have never come to fruition. The brother of a U.S. senator, the Grand Master Mason for the state of California, and the president of the Local Board of Relief, Flint was known around town as the Santa Claus to L.A. and "numbered his acquaintances by the tens of thousands, and his friends were likewise almost innumerable," wrote one LA newspaper. But you won't find Motley Flint's name in many history books these days. It's been wiped away in infamy.

Throughout the 1920s, Flint and a group of high-profile oil men managed to capture the minds and wallets of an entire generation of Angelenos eager to seize upon the get-rich-quick atmosphere that characterized Southern California during the decade. On the surface, Julian Petroleum was one of California's most prosperous oil companies, claiming to have discovered "the deepest well in Southern California" and producing millions of dollars in profits for its investors in an unbelievably short span of time.

In reality, the company's profits were based upon two simultaneous illegal schemes of historic and massively destructive magnitudes. The first was a Ponzi scheme in which the company introduced nearly five million illegal shares into the marketplace, churning out stock like "sausage coming out of a mill," as the L.A. District Attorney would later put it.

The second scheme created a handful of investment pools which purchased prodigious amounts of Julian stock in order to inflate prices and attract new investors, all the while allowing its members to collect usurious rates of interest. The most prominent of these pools was known as the Million Dollar Pool and headed by Motley Flint. Using his celebrity status and well-established connections to raise funds, Flint had little difficulty finding pool members from some of the most recognizable members of the Hollywood crowd, including iconic director C.C. DeMille and MGM Studios President Louis B. Mayer, among others.

When the bubble inevitably burst in May 1927, thousands of investors watched helplessly as their life's savings completely vanished. The crash and the subsequent financial destruction throughout the city proved more than Frank could bear. He grew irrational and violent, obsessing over the scandal and his losses for months on end. He awoke each morning to attend the various legal proceedings stemming from the trial, stalking the conspirators in search of justice. He rarely slept at night, and when he did, he suffered from recurring nightmares of black horses racing towards him and visions of his family drowning to death in mud.

His delirium grew worse and worse as months went on. One night, he yanked his daughter, just an infant at the time, from her crib and threw her "clear across the room and if I hadn't caught her," his wife testified at his sanity trial, "she would have been killed." When news struck that the family's home faced foreclosure, Frank attempted to drive the his Dodge Touring, the entire family on-board, off of a cliff before his wife managed to forcibly gain control of the wheel, instead crashing the vehicle into a tree.

And so the morning of July 14, 1930, marked the pinnacle of Frank Keaton's obsession with the Julian Petroleum Corporation and the men who conspired to line their pockets for generations while leaving the investors without a penny. It was shame that redacted Motley Flint from the annals of Hollywood's history and Frank Keaton from the branches of my family tree, and the memories of both men continued to fade through a diminishing understanding of the past. Only a handful of works -- most notably Jules Tygiel's The Great Los Angeles Swindle -- have preserved the events of the scandal. Even some members of my own family only learned of the details behind my great-grandfather's disappearance by reading a manuscript of this personal history written by my grandmother, Frances Keaton Kogen, revealed to us only in the final months of her life.

In our modern times of Bernie Madoff and Bear Sterns, my family is constantly reminded that this generation of investors is by no means unique, that a historical precedent for the economic turmoil and corporate crimes in this country was set long ago. This July, some eight and a half decades after my great-grandfather's psychotic breakdown and subsequent murder of Motley Flint, my family remembers how little things have changed.

Casey Scharf can be reached at casey.scharf@gmail.com.