Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

The first official U.S. diplomatic post in Cameroon was founded in 1957 during its waning days as a United Nations trust territory. The country was divided between the French and the British; both colonial powers had been preparing their respective territories for self-rule since the end of the Second World War. With other nations, including Morocco, Libya, and Ghana having declared independence, there was confidence among the people of Cameroon that their turn would be next. In 1959, the people of British Cameroon voted to join their French counterparts to form the greater Republic of Cameroon, which was still technically under French jurisdiction. The following year the largely Muslim two-thirds of British Cameroon in the north voted to join Nigeria, while the largely Christian southern third opted to join the new republic.

Independent elections were held for the first time, and Ahmadou Ahidjo was elected as the Republic of Cameroon's first Prime Minister. Although Ahidjo had been a key leader in the independence movement, a political party known as the Union des Populations Camerounaises (UCP) grew impatient with the slow pace of negotiations towards full sovereignty and initiated a guerrilla war to speed up the process. Cameroon became a sovereign nation in 1960. This Moment was compiled from interviews by ADST with Walter Cutler (interviewed beginning September 1989), the first consular officer in Cameroon, and Robert Foulon (April 1988), a colleague of Cutler's. You can read the entire Moment on ADST.org

This Moment was compiled from interviews by ADST with Walter Cutler (interviewed beginning September 1989), the first consular officer in Cameroon, and Robert Foulon (April 1988), a colleague of Cutler's. You can read the entire Moment on ADST.org

CUTLER: As I recall, the Department, in 1956, looking ahead at what was happening in Africa and realizing that most, if not all, of these British and French colonies and trust territories were going to become independent fairly rapidly, did some prioritizing and came out with four countries, or countries-to-be, in which it was decided we had better get a foothold, because they were likely to develop into something of importance in Africa. One of them was Cameroon. And I think the decision was well made, because, as you know, over the ensuing 20 or 30 years Cameroon proved to be a quite-stable and relatively prosperous country.

We had no real direct interest. The resources were nothing like Zaire, for example, the old Belgian Congo, where we already had a consulate general. But it was just a matter of figuring that an American presence [would be important]...

We didn't have the resources to set up consulates to prepare for independence in every one of those countries, so we picked several of them. Kampala in Uganda, I think, was another that was opened at the same time as Yaoundé [the capitol of Cameroon]. So the decision was made in 1956 to establish a presence, a very minimal presence, in preparation for independence. And that's what I did.

... I was it, along with Bob Foulon...I proceeded to look around, rent offices, tried to find houses. I hired a staff and so on. Bob came, I can't remember how many weeks later. And the two of us, together with an administrative assistant and a secretary (there were four of us there originally), opened the doors of the first American official presence in Cameroon. But it was also the first consulate of any kind, of any country, in Yaoundé, the capital.

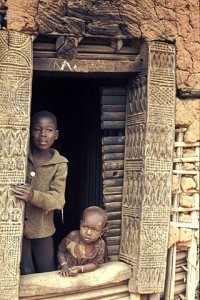

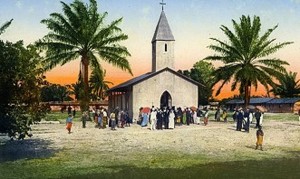

And, of course, Cameroon was a trust territory. The French were administering it, and so there was a French administration. But they were making preparations for a transition to local rule. And we monitored that, working with the French, but we also tried to get to the future Cameroonian leaders. So it was an interesting situation. ... I think there were mixed feelings on the part of the French. Obviously, there was some hesitation, some wariness in the private French community, as well as perhaps in the administration. On the other hand, I don't recall an awful lot of hostility, animosity on the part of the French. It wasn't like the Ivory Coast, where they had a big commercial interest. They had some, but not a great deal, in Cameroon. The only Americans were Presbyterian missionaries, who had been there for some years.

... I think there were mixed feelings on the part of the French. Obviously, there was some hesitation, some wariness in the private French community, as well as perhaps in the administration. On the other hand, I don't recall an awful lot of hostility, animosity on the part of the French. It wasn't like the Ivory Coast, where they had a big commercial interest. They had some, but not a great deal, in Cameroon. The only Americans were Presbyterian missionaries, who had been there for some years.

... There weren't that many educated Cameroonians there at that time. The country was not yet independent. Many of the Cameroonians were young students still in France. But we made headway, so that when independence came I think we had a pretty good rapport.

One had the feeling of considerable isolation in Cameroon, and yet you also had the feeling that there was an increasing interest in what was going on. And there was a particular interest in Cameroon, because, in those days prior to independence, there was a movement called the UPC, Union des Populations Camerounaises, which was believed to be heavily backed by Moscow.

This was a radical nationalist group, which was not only fighting to get the French out, but was really jockeying for political power prior to independence vis-à-vis the other groups, which were sanctioned by the French. This made for some pretty dicey days. We lived with a curfew for quite awhile. And there were some pretty gruesome massacres that occurred right in Yaoundé.

These UPC guerrillas would come out at night and, just trying to create a certain amount of chaos, they would go for the French. They murdered any number of French people while we were there. There was a great deal of tension at the time and uncertainty as to whether or not the French and other Cameroonian elements could handle this, or whether, in fact, the place might be ripped apart by this movement if it really started to gain momentum. For this reason, Washington tended to follow events in Cameroon perhaps more than otherwise would have been the case.

FOULON: My instructions were to open this post as fast as I could. We actually got it open one month from our arrival. The reason that we broke our necks on this was, at that time in Cameroon, French Cameroon that is, the word "independence" could not be uttered; it was absolutely forbidden. The Africans were not allowed to print it, the French were not permitted to say it, but everybody knew that it was going to happen. So I decided that it would be very cute to open the post on the American Independence Day [July 4, 1957; the opening is now commemorated on July 5] and we put out invitations talking about the day of independence and so forth, the American independence - in French of course. We invited a nice assortment of French and African leaders.

So I decided that it would be very cute to open the post on the American Independence Day [July 4, 1957; the opening is now commemorated on July 5] and we put out invitations talking about the day of independence and so forth, the American independence - in French of course. We invited a nice assortment of French and African leaders.

Well, the French didn't like it but they had to lump it, having helped American independence and recognizing what a cute stunt we had pulled; they did not object, at least openly. The Africans came around and thanked us to the skies for having helped them in their battle for independence by opening our post on the Jour de l'Indépendence.

When we arrived there, most of the French thought that we had come to sell arms to the rebels who were being supplied actually, at the time, by the Chinese Communists. They were down in two particular tribal areas near the coast.

All of this was somewhat promoted by the fact that one of the main tribal areas was the location for the main active areas for American Presbyterian missionaries who had established the first schools in this area; they ran a teachers school and so forth. They were actually being accused by the French of stirring up the African rebellion.

I can remember one of my first real challenges was when then High Commissioner Pierre Messmer, who eventually became Prime Minister of France, called me in. While very stiffly sitting behind his desk, he told me that one of our missionaries would have to leave unless the mission was wise enough to transfer him to another post outside of the rebellious area. This was because they thought that they had evidence that he had actually harbored the leader of the rebellion, a man named [Ruben] Um Nyobé [leader of the UPC].

Well, I could see that this was a test for me as well as the missionaries. I jumped into the car and went down to their headquarters and remonstrated with them and plead with them. Fortunately, in order to get better acquainted with them I had just spent a week at a missionary retreat, so I knew them all and I knew how they thought, felt, and so forth.

They were very reluctant to let the French tell them what to do because they were before the French, and even before the Germans. Fortunately they did relent and this man was transferred and we avoided the incident, and our relations with the French went up continuously after that.

[The head of Autonomous Cameroon, Andre-Marie Mbida] was from a tribal group right around the capital. As I recall he was a strong Catholic and bitterly opposed by the Northern groups who were dominated by Muslims. He was very shortly replaced by Ahmadou Ahidjo who was the leader of the Northern group, but had enough European experience and education in the south to be able to bridge the differences between the North and the South. Even after I arrived, and much more beforehand, there was a real fear that the North would try to separate from the South... I can well remember being lectured by Ahidjo on a trip I made to Cameroon -- several trips really -- after independence and after I had left my tour there. He always entertained me very cordially at the Palace and at one point he lectured me.

I can well remember being lectured by Ahidjo on a trip I made to Cameroon -- several trips really -- after independence and after I had left my tour there. He always entertained me very cordially at the Palace and at one point he lectured me.

He said, "You Americans, you have to realize that all of these parties that you see here in these African countries with different names that seem to reflect European and American kinds of political divisions, those are just names! They are really reflecting other things: political rivalries, tribal rivalries, and even religious ones. That is the nature of the African condition. We have to deal with it and that is why we find useful, at least in the early stages, to have single party systems, Le Parti Unique."

Cameroon actually was broken into two or three different pieces, and one of the great accomplishments of French Cameroon in politics was the union of the two Cameroons. The Communist rebellion was based on this as a leading line, I think it was called "L'Union des Peuples Camerounais" or du Cameroon, or the Cameroon Union.

Eventually they had a vote and the main part in the Southern area voted to join French Cameroon and not Nigeria. This astounded the French Cameroonians! They never expected it to happen even though they had been pounding drums for it for years. They were literally flabbergasted.

I remember Ahidjo telling me "What do we do now?" They created a bilingual state and a bilingual parliament and pretended to be Federal for a while, though I don't think it is anymore.

[Yaoundé] was about thirty or thirty-five thousand people, maybe two thousand Europeans; a pleasant place up in the hills - cool at night, just on the verge of the savanna and still in the tropical rain forest, very damp most of the time - but a very pleasant spot. Douala was the big city down on the coast, a steamy place, it rained everyday with the highest rainfall I think in the world. People who lived there said they began to like it, but I can't imagine why. I always avoided the place as best as I could.

My Office Director [at the State Department] was Vaughan Ferguson and, in all my time out there I never got a single instruction by letter or cable or in any other form, not once. It was a marvelous experience of old-fashioned diplomacy in a situation where you have to make the decisions on the spot. You are "Mr. U.S." and nobody is there to tell you anything else. There were a few cases where there were real decisions involved. To some extent [the State Department was paying attention to Cameroon,] particularly with regard to the Trusteeship Council and the date of independence, and how to play the rebellion, and how to deal with the French. They listened to it quite a bit; I assumed that somebody beyond Vaughan Ferguson had some interest in all of this.

To some extent [the State Department was paying attention to Cameroon,] particularly with regard to the Trusteeship Council and the date of independence, and how to play the rebellion, and how to deal with the French. They listened to it quite a bit; I assumed that somebody beyond Vaughan Ferguson had some interest in all of this.

My fondest memory is really a very warm relationship with the President Ahmadou Ahidjo, then Prime Minister, and working with him to achieve a successful outcome in the move toward independence.I can remember that the big question was whether to try to have an election before or after independence, particularly with the rebellion going on and so forth. The French managed to consult with me outside Yaoundé. I happened to be on a trip to Douala and the High Commissioner got himself down there and I was just invited for drinks. Before I knew it, we were in the most serious political conversation I had there.

They were wondering what to do about the UPC, the Communist Rebellion Party. My reaction, which I advanced very forcibly -- and here is where the real hip-shooting with no instructions whatsoever occurred -- I said "Just forget them, just go ahead and achieve independence." I did raise the question as to whether or not to have an election beforehand, and they were scratching their heads and I was scratching mine and we didn't quite know how to handle this in light of the fact that it had to pass through the Trusteeship Council.

So I went over and saw Prime Minister Ahidjo and I outlined the problem and told him about our discussions; he hadn't known about them actually.

I said, "You are going to have to be the judge here, should we have an election beforehand or afterwards?" He said, "Let me think about it and I will let you know."

He said, "Let me think about it and I will let you know."

In about two weeks time he called me back and said, "I think we should just go ahead and then we will have an election afterwards."

So we accepted that and we called in the visiting mission and they made their report, and Cameroon became independent without an election... It was not a very democratic decision perhaps, but probably a very wise one.