I recently had the pleasure of visiting with the painter Lennart Anderson. He is not, I gather, widely known, but he commands the awe and respect due a legend among those who do know him, and this narrow group is, itself, a fairly august crew of art enthusiasts.

Anderson's work of the past couple of decades slips effortlessly into the stream of painting. It is a stream that has flowed for centuries, and will flow for centuries more. Anderson's work is filled with arcadian visions of greenery dipping into black, vivid blue skies and nude classical figures in pinks and oranges, graceful and fluid, shimmering as if glimpsed when they appeared for a moment, laughing, before vanishing back into the forests in which their endless dramas unfold. The stream of painting, as Anderson paints it, has cool, clean water and a winding course alternately dappled in green shade and set aglow by a temperate sun.

My father talks about Haydn as a composer's composer. I think he means that Haydn did things with music which it takes an expert in music to appreciate. This fairly describes Anderson's painting technique as well. He applies paint to the canvas with a fully integrated understanding of the relationship between paint as a physical phenomenon, and paint as a medium which depicts. He paints with the intuition of experience, with verve and self-confidence. His brushstrokes are neither too little nor too much. There is a poetry to their balance which might be perceptible only to those who have grappled with the intricate demands of painting. What difference does this colossal skill make in the work as art? Only this -- that, seeing it, the mind sighs with pleasure and relief. It says, "I trust the authority of the eye and hand behind this work -- I can sit in the company of this work, as I sit in the company of art, and I will not be assaulted, cheated, or abused; I will come away elevated."

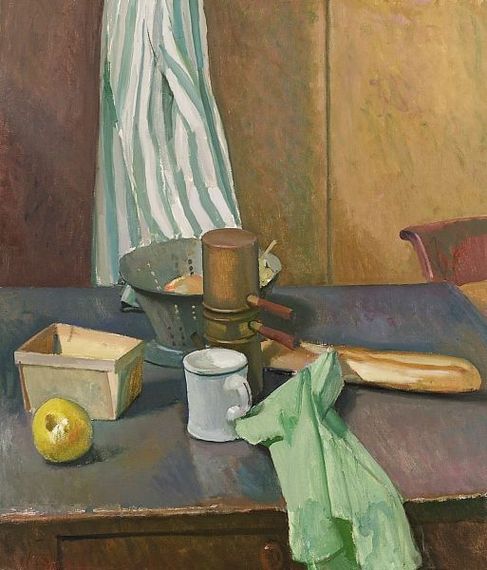

Anderson's work did not always show these qualities. Talented from the start, he spent many years painting the usual repertoire of modern representational subjects: still lives, studio nudes, street scenes and portraits.

As his work progressed, he dove further into each subject, repeatedly inquiring of it what it was as his powers of perception increased.

Ultimately, he came to see that all these separate subjects were separate in appearance only. At their root, they were one thing, verses in a continuous song of Being. Turning his head to look from a different angle, he recognized that this eternal Being was the same as the Being of myths. Neither facet of reality -- the quotidian and realist, and the mythical and magical -- was more true than the other. He acknowledged that he was so constituted as to prefer the mythical facet, and began to elaborate on his arcadian scenes. They contain all that his work has ever contained.

Let's compare nudes from the start and most recent stages of Anderson's career.

In this early painting, Anderson chases after form, describing every little thing with an over-eager tracery of lines and a literal-minded application of value which trends, in its excitability, toward pure white. That pure white is characteristic of the nudes of young representationalists. They do not see a complete body, but rather a pile of parts. Studying each part, they adjust the brightest value in that part to the brightest value they can paint. This traps them in an over-brightness which it takes years to subdue. Anderson has partly subdued the over-brightness here, but in an analytic sense only -- he has keyed in compositional darks by fiat, in the arm and face, and in the background. Getting the right mediums and darks is not, ultimately, a matter of compositional ideas or using darker paints. It is a matter of comprehending subjects holistically.

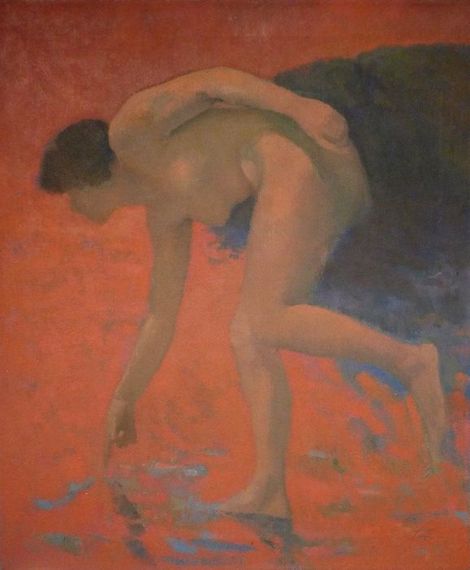

Now consider a recent figure.

Observe how effortless and complete this looks. The range of values is much smaller, but their arrangement by strict priority lends them more apparent variation. The brights, dim as they are, read bright, because Anderson has let go so much in the mediums and darks. The pose and composition are complex but appear simple, because they are organically unified into a shape like a medieval drawing of a shooting star.

These descriptions of the two paintings refer to the mechanics of painting, as if there were nothing more to discuss in Anderson than his technique. But this would be a misstatement. The technical analyses serve as a means of drawing your attention to the progression of sensuality and formal elegance in Anderson's paintings. And the sensuality and formalism themselves form the language in which he demonstrates a key insight, one I have long pondered: that a painting is not an idea. Ideas can be shoehorned into paintings, just as Tarkovsky complained that a play could be shoehorned into a movie. But the idea is to painting just as the dramaturgical script is to film -- related, but not the same; when too forcefully applied, a parasite suppressive of the nature of the unwilling host medium.

In the letting-go of the later work, Anderson allows the painting to breathe, to become itself as a painting. The warm colors shimmer over a cooler surface, the space rotates between red, green, and blue, and the figure seems not to be caught between motions but to be still moving, rotating too. It does not "mean" anything; it testifies only to joy in being, in moving, in seeing, and in painting. This joy-in-painting is another way of describing how Anderson is a painter's painter. But his paintings are not for painters alone -- his work invites the layman viewer to join in this joy. He makes the joy of the professional available to the tourist.

We had sad occasion recently to discuss the concept of late work: the insightful work done near the end of an artist's career, when that artist has both mastered his or her medium and dropped the things that trial and error proved were unnecessary. In technique, late work often looks crude; in effects, less flashy than the work churned out by youthful ambition. Late work tends to be both profound and simple.

Anderson's newest work is late work. The early nude above was painted in 1955. Anderson is 85. He is nearly blind, and paints from necessity out of the peripheral vision he has remaining.

He presents the very model of how we should all hope to live if we live to be 85. He is lanky and cantankerous, gleeful and good humored. He spends his time in a skylit studio, surrounded by paintings and drawings and books, attended by his cat and family and friends. He studies art, he talks with artists, he makes art, and he takes pleasure in making art. His energy and his facility are diminished, but his work is better than ever. The brightness manifest in his work is manifest in his way of life as well. Wise art need not come from wise men; I do not know Anderson well enough to know if he is wise. But his work is wise, and he lives well, and this is is a very inspiring thing. All best wishes to the man, the artist, and the art.

_____

Lennart Anderson online: http://www.lennartanderson.com/