"Young people, and especially our children, can revive our capacity for wonder at the world and a sense of intimate connection to it. I felt closer to the landscape because I saw my daughter come alive to it with an intensity that no longer comes so easily to me."

I stand on high ground looking out at the Vale of Evesham, a wide expanse of grass, rows of darker trees and distant hills of patchwork green. Clouds cluster overhead, sometimes seeming to threaten rain, sometimes parting to admit slants of sun and patches of bright blue. My daughter, who's come with us on this trip to England, becomes part of the landscape, her scarf adding a different note of azure, her face lit with a touch of light. I feel a rush of love for her and for the landscape as well.

On our flight to England, I'd read Mark Doty's Still Life with Oysters and Lemon: On Objects and Intimacy. It is a book about still life pictures, but also about love, loss and our hunger for intimacy. The book moved me, and in the course of a ten hour journey, altered my understanding of why I travel, of why I need to travel.

I'd had a surface grasp of what I looked for in getting away-- to break with my work, with the discipline, the effort, the disappointments, the unending nature of revision. I also longed to escape our distinctly American culture of individualism and overwork. My English friends work hard too, but their lives have always seemed more balanced, more leisurely and more pleasurable than mine.

Traveling, I also knew, involved what I thought of as an opening to the world, an expansion of the capacity for pleasure. When I travel I begin to focus, to concentrate-- not on my work-- but on landscapes, art, music, food. Reading Doty, however, made me aware that there were deeper layers, emotionally speaking, to this concentration and this opening and to their accompanying delights. The effect of looking and looking, Doty writes (he is gazing at a still life involving oysters and lemon) is "love . . . a sense of tenderness toward experience, of being held within an intimacy with the things of the world."

Reading Doty changed my perception of what I was to experience in the English countryside. It was more than pleasure, it was love I felt in looking out at the Vale of Evesham and at my daughter in her blue scarf. It was tenderness toward experience that I felt in Hidcote Gardens when I came across a velvety green path, bordered by tall hedges that seemed to go on forever and to promise unseen possibilities.

Doty asks "is that what soul or spirit is, then, the outward flying attention, the gaze that binds us to the world?" I can't answer his question, but I know that reading him made me understand for the first time that my own "looking and looking" gave me a sense of being bound to, and rooted in, the world-- of feeling at home in it. As a child of distant parents, feeling at home in the world is something I've pursued for most of my existence. No wonder I travel.

Describing what we have seen, Doty writes, is an "inexact, loving art, and a reflexive one." In writing about what we see, we "come closer to saying who we are." Though, in my case, writing what I see feels more like trying to become the person I want to be.

I carry love of my daughter within me no matter where I am, but I want to feel intimacy with green paths and leafy vistas and to hold that love within me too. And I want that connection without my usual ache of nostalgia, without my familiar longing to re-experience what I once felt for the English countryside when I was much younger, when I taught nineteenth-century British literature, was married to a man I loved, who later died of AIDS, when the lush verdure of the English landscape was overwhelming. I want to feel that the intimacy I experience in the present is-- enough.

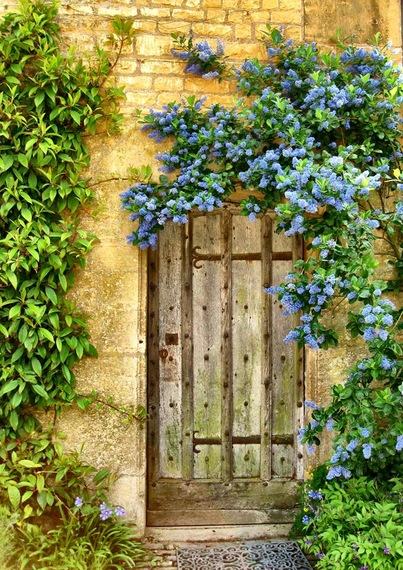

I began to see that it had been a desire for intimacy without nostalgia that prompted me, in part, to persuade my daughter and her boyfriend to come with me and my husband to England. Young people, and especially our children, can revive our capacity for wonder at the world and a sense of intimate connection to it. I felt closer to the landscape because I saw my daughter come alive to it with an intensity that no longer comes so easily to me. She shares my passion for gardens, for ancient doors draped with ceanothus, for pink roses splayed against a brick wall. My connection to them was more palpable because she felt it too. And, more simply, my love for her magnified my tenderness toward all three.

Doty, of course, reminds us that everything is "evanescent. " In still life pictures, the bounty of shimmering things artfully arranged on a table always bear signs of decay-- an insect, a flower whose petals are coming loose, a fruit that is overly ripened. The intense intimacy we feel when we study a landscape or a painting passes-- as will we. But we can carry the imprint of that tenderness within us. And, despite, or because of, their evanescence, the moments we do spend "wrapped in layers of intimacy with the world" can feel like "perfection."

Earlier on Huff/Post50: