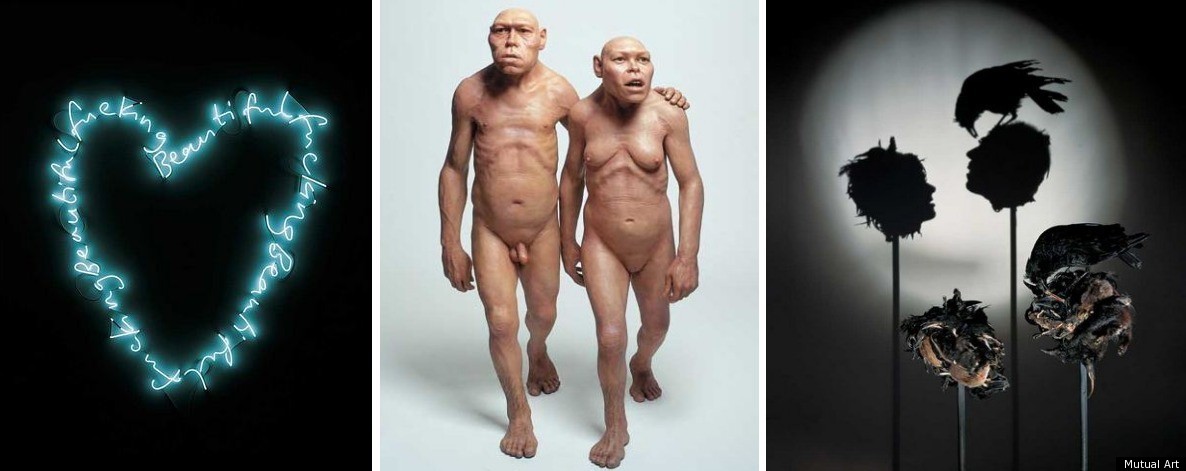

Their works range from effervescent, large-scale light installations to graphic art illustrations, to jaw-dropping sculptures made from materials like taxidermy animal parts, scrap metal and peanut butter. Even their website is decidedly nontraditional, in the deepest sense of the word: "Welcome, Motherfuckers!" is the greeting that welcomes visitors upon entry. They've successfully done away with false politesse and formality, and remain staunchly unapologetic about this fact. Suffice it to say, everything about their multi-faceted artwork grabs your attention, and heaven help us, we just can't stop looking.

We're talking about British collaborative artists Tim Noble and Sue Webster, who first took the art world by storm nearly fifteen years ago, and the two show no signs of slowing down (nor would we ever want them to). Their creations play both literally and figuratively on the juxtaposing relationship between 'light' and 'shadow', so it's fitting that these are the titles of their two main bodies of work. "Our work is incredibly unsocial," Webster has said. "There has to be complete darkness because you need to give the light and then to take it away again.

Their pretty, crowd-captivating light-installations explore a common thread that connects all of their varied masterpieces: investigating how people interpret abstract images through applied meaning. This is most evident in their cutting-edge "rubbish" sculptures (part of the shadow work), where the old adage "One man's trash is another man's treasure" rings especially true. Works are made from discarded objects and later assembled into innovative sculptures that leave audiences scratching their heads in "how do they do it?!" disbelief. Which, according to Webster, is one of the duo's goals. "The main challenge is to find a way to maintain the suspension of disbelief," the artist told MutualArt in a recent interview.

What's so awe-inspiring about their work? These are collaborative pieces with manifold meanings. They please the eye two-fold, like optical illusions: there's the sculpture itself and then the image it projects. And no, we're not just speaking metaphorically here. Case in point: Check out their tantalizing fruit sculpture. The fruit tempts the audience in what looks like a stone obelisk of sorts, with the top and bottom halves of the piece connected by cable wires. But shine a light onto the piece, and you'll see there's more there than meets the eye - the fruit transforms into a silhouette of a man and a woman, back to back, seemingly imprisoned in a cage, as "milk" and "honey" pour freely from both bodies. And the sculpture's apt title, The Original Sinners, certainly makes us think of Adam and Eve, tempted by the forbidden fruit and subsequently punished for it.

It's a triumvirate of meaning - the sculpture itself, the projected image, and the relationship between the two - eliciting a lot of gasps and 'wow's from even the most articulate art critics.

So just where in the world did Noble and Webster come up with this idea? We learned about their unorthodox artistic approach when we spoke with one half of the dynamic duo - Sue Webster was initially inspired to use nontraditional media after a particularly harrowing experience she had while in art school. Webster had intended to pursue a career in painting; at least, that was the plan when she enrolled in the fine art program at Nottingham Trent University in the late 80's. Fate, it seemed, had another idea in mind. While visiting a music festival with her then-boyfriend, she had what can only be described as a very bad trip. "I consumed a very tiny and innocent looking pill called a micro dot, which turned out to be an extremely strong hallucinogenic," Webster candidly explained. "I lost sight of [my] boyfriend, and so those terrible twins - 'fear and paranoia' - decided to take me by the hand and lead me on a 14 hour 'fun' ride." The artist vividly remembers every detail of the ordeal:

"The ground melted beneath my feet and I thought I was being swallowed up by the earth; my shoe laces turned into writhing fluorescent green snakes that began to wrap themselves around my legs; my pupils dilated to the size of two goldfish bowls and it seemed that everybody was peering knowingly at me through my inflated goggles. The apples on the trees that wore little Michael Jackson faces were talking to me, and I remember seeking refuge in the Samaritan's tent (which was full of other acid casualties), and I became aware of every single molecule in the Earth's atmosphere being like a three-dimensional paisley-patterned curtain. I paused for a moment to consider if this was Heaven or Prince's Paisely Park...My peripheral vision narrowed, and I was aware of traveling down a dark tunnel with a bright light at the end that was calling to me."

While terrifying, the experience had a profound impact on Webster's artistic approach. Upon returning to art school after the summer, she switched media and transferred from painting to sculpture; as she says, "I started to see things in 3D. That's where I met Tim - he was trying to take a plaster cast of a live fish in his studio space which was underneath the staircase, and being a poor student, he took the fish home and ate it for his dinner."

Soon after, the two began collaborating and the duality of their partnership is reflected in their art. In terms of their shadow works, we were curious to know which came first: the actual piece or the projected image it created? Webster isn't sure of the exact moment of epiphany, but she says the idea stemmed from challenges the duo faced while working on one of their light sculptures. "I remember being frustrated whilst wiring an early work, Toxic Schizophrenia, as I had to wait for a shipment of bulbs or something, and the idea for the shadow sculptures came out of the desire to keep making," she says. "While experimenting with the assemblage of personal items and household rubbish in the studio one day, we shone a spotlight onto one of our gestating forms and were fascinated by the shadow formed on the wall. With the kind of conceptual leap that can only be achieved through the trial and error of studio practice, we began sculpting the mounds of rubbish so that our own silhouettes could be read in the shadows." What came from this experimentation was the team's first shadow sculpture, Miss Understood and Mr. Meanor.

This innovative approach spiraled into a series of other "rubbish works" that played off of their light sculptures, and explored a subject that both Noble and Webster continue to address in their art - redefining how abstract forms can be transformed into figurative pieces and examining how people process these relationships. The artists use materials like scrap metal and cable wire, as well as less traditional media such as animal parts, cooking oil, and even urine. (Not for the faint of heart, animal parts are also the favored media of another innovative artist, Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva. Read our interview with her here.) Webster is undecided about which media she likes best. "What's nice about working with different materials is that there is no direct way in which to join things together, so every new method is a totally new experimental experience which keeps the work fresh," she explains. "I guess it's obvious that one joins metal together by welding, but there exists no textbook explanation of how to join the body of a rat (something soft and furry) to the wing of a Rook."

Webster says the core relationship between the works and the projected images are the same, regardless of whether the medium is stuffed squirrel or sterling silver: "It's the realization of one of the most avidly pursued artistic goals in modern and contemporary art - the fusion of representation and abstraction." This fascinating fusion is explored pictorially in the appropriately titled British Rubbish, an art book recently released about Noble and Webster's work from the past fifteen years, with essays by Jeffrey Deitch, Michael Bracewell and Nick Cave.

If you look at their extensive and varied oeuvre, there are some unifying threads: The husband-and-wife team are celebrated for mixing elements of punk and counterculture into their unique art. From their "anti-monuments" to their light works and their parallel shadow pieces, nothing about their art is business as usual. Much of what they do plays off of dichotomies and a strangely seamless marriage of opposites. This is reflected by the relationship between the artists themselves. "We have a polemic relationship," Webster says. "A polemic is a form of dispute, wherein the main efforts of the disputing parties are aimed at establishing the superiority of their own points of view regarding an issue. Along with debate, polemic is one of the more common forms of dispute. However, unlike debate, which may seek common ground between two parties, a polemic is intended to establish the supremacy of a single point of view by refuting an opposing point of view." Opposition, in this case, seems to work in the artists' favor, as the polar aspects of their pieces compliment each other, fusing images of gender and sexuality, violence and consumerism - all the ills and issues of the modern world in a smart, decidedly provocative manner. "I always find that the brain is continuously unfolding the next idea whilst attempting to finish the last," the artist stated at the end of our conversation, leading us to the happy conclusion that Noble and Webster have more slyly subversive creations on the way. We can't wait to see what surprises will emerge from the shadows...

Written by MutualArt Writer Lauren Meir