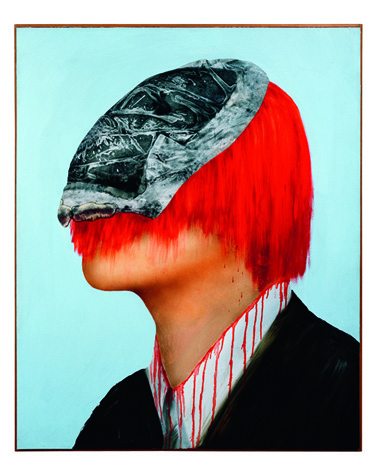

Llyn Foulkes. Who's on Third?, 1971-73. Oil on canvas. 48 x 39 in. (121.9 x 99.1 cm). John Jones Collection.

One thing that I cannot transcribe from my interview with Llyn Foulkes is his sense of humor. Throughout our conversation, his wry take on the art world, corporate influence and his own foibles, kept making me laugh. While he can appear critical of the world around him, he is also the first to point out his own missteps.

Foulkes is famous for being an iconoclast, going his own way and not playing the games one associates with the typical networking and shoulder rubbing that goes on in any arts field, especially in LA where image is so important. Foulkes career started with shows at Ferrus Gallery, Pasadena Art Museum and Oakland Art Museum, but his career faltered after being an essential part of MOCA's Helter Skelter show in 1992. For years, local artists knew that Foulkes was not getting the recognition he deserved. Foulkes told me that, because his work was so anti-establishment (particularly his anti-Disney multimedia paintings), that artists whose work was more palatable for buyers to collect, displaced him. In recent years this has changed, starting with the inclusion of Foulkes' work in shows at the Hammer Museum, the Venice Biennale and Documenta 13. His upcoming retrospective at the Hammer Museum, opening early next month, is sure to be one of the best shows of the year.

We started the interview with Foulkes giving me a mini performance on "The Machine," his one man musical instrument comprised of horns, organ pipes, cow bells, bass and percussion. Foulkes sings about LA's smog, freeways, and movie stars, while he plays a mash up of folksy, jazzy, and vaudevillian blended influences. Next Foulkes shows me a print of his young daughter, where she is making faces in a photo booth. The print will be produced in a small special edition for the Hammer show.

LF: In 1975, my daughter Laurie was then 14 and at the Santa Monica pier, for a quarter you could get 3 shots in the photo booth. I dressed her like a Catholic schoolgirl and said, "You just make a different face right before the light goes on." Not one face there is the same. If you really look at these shots, you say, "My god, how could she do that with her face?" That is a conceptual piece, 1975. It was my idea, to have her respond to me, because she is part of my work, and part of my life. The weird thing is, considering what I do, if you look at the light behind her, you see faint white Mickey Mouse ears.

TH: There is a white mouse ears glow around her, how did that happen?

LF: It just happened.

We walk upstairs to a sitting area where every inch of the walls are covered with an array of objects that Foulkes has collected over the years. Foulkes describes some of the things on his walls to me: a preschool drawing by his son, small art pieces or cards from George Herms, Dennis Hopper, Lloyd Hamrol, and Jeffrey Vallance, a rhinoceros skull, a dolphin skull, a nine foot long whale jaw bone, a wasps nest, a hummingbird nest with an egg in it, a toothbrush gun for children, the first page of the 1934 Mickey Mouse Club manual, and ticket stubs from a 1965 Beatles concert at Dodger Stadium.

LF: The Getty wanted to take my whole living room for PST. They wanted to put it in the assemblage area. I said, "No, no, it's too personal." But then I thought, "I could get rid of my whole past this way," because that collection represents everything from my past. They'd pack it all up and take it to the museum where they would reconstruct the whole thing. Then the show would travel to Berlin and they would send it there.

TH: So they wanted to recreate your walls by photographing the way they look at present and then rebuilding them at the museum. Then would they rebuild it for you back here at your studio?

LF: No, they would return it to me in boxes. I wanted to replicate the wall in permanent sections that could easily travel as is and be sold. That way I would really be getting rid of the past. To their proposal, I just said, "That's the stupidest thing I've ever heard in my fucking life. You are wasting so much money." I don't like the idea of wasting that much money.

Francois Pinault, he's collecting my stuff now, he was up here and said, "That reminds me of Andre Breton, he had a studio that was like this and they were so sorry that they were only able to save one case." Then I look at my stuff and think it should be saved. But then the other part of me goes, "What is so fucking important about my life that it should be saved this way?" I go back and forth on that, it makes me feel like a real narcissist.

TH: You've created a visual manifestation of how you think. Most people don't do that, we don't get to know their thought processes. You have a lifetime of making an outer example of the things that triggered your interior inclinations.

LF: Nah, I'm just decorating.

Llyn Foulkes in his studio, Photo by Tracey Harnish

TH: How did you become so interested in Disney as a corporation and it's corrupting influence on children?

LF: I watched the whole take over of Disney, after Walt Disney died. My former father-in-law, Ward Kimball, was one of the animators and one of the original "Nine Old Men." So I learned a lot about what was happening there and it was very interesting; I started looking at the marketing aspect of it. Ward didn't think anything of it because he thought people liked it. But I looked at it and thought about how they were planting ideas in children's minds. If you look at the Disney channel you'll see the same thing. It's all about how they can keep children doing something they can market.

TH: Do you still love LA in spite of all the phoniness? Or is it love/hate relationship?

LF: I think it's love/hate. I think everybody has that love/hate thing and then we watch the city and developers tear down buildings they shouldn't tear down.

TH: Do you mean landmarks or architecture that is relevant to the city's history?

LF: Yes. It's like going to Rome and saying, "Ok those are too old, we have to destroy that." The original studios, you just saw them all disappear. The whole Echo Park area, everything that was the first Hollywood, is gone now.

TH: Maybe LA wants to get rid of it's past the same way you were saying, you'd like to get rid of yours.

LF: That could be. Thank god they saved the old downtown theaters. Nobody cared about downtown and everybody went out to the Westside, so it just kind of stayed that way, got run down, got swap meets, all due to inertia.

When I went to art school, the first drawing class I had, we were sitting up on 2nd and Grand Avenue drawing these two big Victorian houses where MOCA is now. The city wanted to put high rises up there, so they tore them down. They could have put the high rises anywhere. Angel's Flight went up to it, there was a path down to the library, and the whole of Bunker Hill made sense. Like Olvera Street, only better. It would have been a great tourist attraction; it's the dumbest thing they ever did.

TH: Speaking of tourist attractions, what do you think of Levitated Mass, at LACMA?

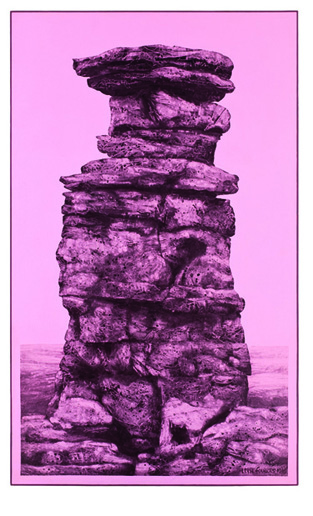

LF: Yeah, what about The Rock (as it's called locally)? If you want to see some rocks you could go to Utah and see some rocks hanging right over your head, that look far more precarious than seeing a rock sitting over a concrete ditch.

Llyn Foulkes. Portrait of Leo Gorcey, 1969. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 107 3/4 x 64 3/4 in. (273.69 x 164.47 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the artist and purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art (69.141). Photo by Sheldan C. Collins.

TH: What about Chatsworth? There are really beautiful rock formations in Chatsworth.

LF: That's what inspired my first rock paintings, was Chatsworth.

TH: As a kid I spent quite a bit of time in Chatsworth and the first time I saw your rock paintings, I was reminded of that landscape.

LF: In Chatsworth I captured images that are almost head like. In fact they all have resemblances to heads and faces. I got a sterioptican camera that created a double image of the rocks. I made paintings that were influenced by that. So obviously I got into the whole pop art thing too. Everybody in a sense was taking from everybody else.

I saw a whole different Los Angeles. The Los Angeles I like is the one connected to Hollywood and it's environment. Hearing about Hollywood on the radio while growing up, glorified all of LA. A lot of art has been based on celebrity but doesn't go far enough though.

TH: The images of you as Superman having anxiety attacks, those seem to take on the idea that celebrity isn't what it appears to be.

LF: But you know, that all becomes about me too. Those things represent not only what was going on out there but also what was going on inside with me.

TH: When people say their art is in no way about them, I don't entirely believe it.

LF: Yeah, I don't either. One time I was in Irwin's (Robert) studio and it was when he was painting all those pictures that he kept hidden behind curtains. This was when I was first at Ferrus Gallery, and he was watching TV and he's working on a painting. I say, "Why are you watching TV and painting?" And he says, "I'm trying to become selfless." See, I understand where that comes from, but you can't really become selfless. You can't become selfless because you are the hand that is doing it; your hand is also being controlled by your brain.

TH: It seems to me, if you are watching TV while you are painting, you have a certain kind of information that is coming in and will influence you in what you are doing.

LF: You know I never listen to music when I'm painting. Never.

TH: So it's just all you.

LF: I'm in my paintings, so when I'm thinking about these things, they come out in my paintings whether I like it or not. I think that goes back to everyone being so programmed into music too. Where you can have so much all the time, so that a person will be walking through the woods and they'll have their headphones on. It's like I'm in a movie now because I have music to the movie going on in my head.

TH: Your own personal sound track.

LF: You have your own sound track. Wow, has Hollywood brain washed you. You can't even listen to what's out there anymore. We don't want to solve our problems; we just want to let music put us in a trance. Visuals are getting faster too. You are constantly seeing images fly by and we are told what is supposed to be sad and how we are supposed to feel.

Foulkes stops for a smoking break.

LF: I have a lot to live up to. It's stressful.

TH: Is it because of the preparation for the retrospective?

LF: Yes and it's happening in general because as it goes through my whole life and I see periods of change, I also see periods of me being a real asshole. I was very self centered. I look back at my life and memories that I had blocked out, that were buried, are now coming back. It's like intensive therapy without a therapist.

TH: Since you've been a part of the LA art community for so long, can you say if there any long time LA artists that you think are good or doing work you think is notable?

LF: There are quite a few people doing good painting, one who comes to mind is Lisa Adams. She is really interesting and hasn't gotten her due. I particularly like the painting she has been doing the last couple of years because she really takes chances and she is very dedicated to what she is doing. You don't see that kind of dedication very often. I've seen her grow, particularly in the last few years.

TH: Do you ever regret being so honest, coming right out and saying how you feel about LA, the art world, and Disney?

LF: It's just who I am. Now that I think about it, it's like, "Watch your mouth you stupid ass." I couldn't help myself. I didn't go around with a lot of artists. I didn't pal around with a lot of other people. I always had work to do. I didn't have people doing my work for me either. I even made all my own stretcher bars and stretched everything myself. Having a wife and a child, just being out of art school, having to drive a taxi and work at the hand painted picture factory, there wasn't a lot of time to run around and play.

We're into big now, bigger, brighter faster. It's the only thing that is important. Even the advertising on television, a commercial for Time Warner, asking kids, do you think your grandma would like this? This is really fast, so what is better, faster or slower? Faster, faster is better. Bigger is better too, like The Rock. No one is going to make a fuss about the little things.

TH: It's the way our whole society is. We are getting so much information. I read that 52% of the people who are watching TV are also using their cell phones at the same time.

LF: Is that supposed to train our brains to make us smarter?

The Llyn Foulkes retrospective will be at the Hammer Museum February 3 - May 19, 2013.