I don't know about you, but I'm already missing AMC's "Mad Men": nevermore will I see Joan's clothes and fulsome figure striding into the office; Peggy's terrible design sense regarding her own clothes, coupled with her rising sense of self-worth; Roger's off-handed remarks, full of irony and wit; and most of all, Don Draper, who has it all -- striking good looks, sexual magnetism, business acumen, and finally, lots and lots of money. But these are not my reasons for regretting Don's departure. I am drawn to him because he is struggling mightily with the worm at the core, a value system that is way off kilter, causing him and those who love him a plethora of pain.

Why are we so compelled by Don? Well, it is true that a good man is hard to find -- but the bad ones are so much more interesting, at least in fiction, if not also in life. Don is not Machiavellian, he doesn't really mean to hurt his wives, his lovers, his partners -- no, he is an unconscious bull in the china shop of relationship. He keeps a dark secret that would undo him if it were revealed, but that secret becomes a preoccupation in his subconscious, so distracting that he quite unwillingly becomes a person who undermines his own formidable gifts and leaves a trail of broken hearts and lives in his path. The fact is, Don can't be intimate. He can be gentle, kind, generous, but no not intimate, because he has a hidden history that defines and undermines him at every turn.

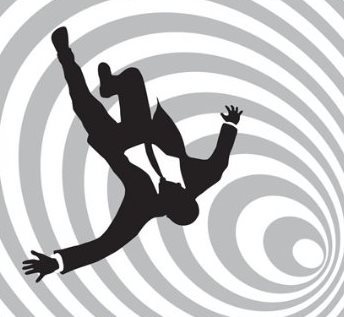

And Don is undone not only by his history, but by the consumer culture that has been the context for all our lives since the '60s -- the inundation of advertising driven by corporations, and the ad agencies that manipulate for money. Don has become a hired gun, and no one is better at the fast draw. So the man who is living a lie in his personal life fits perfectly into a culture that is grounded in anything but the truth. The brilliant visuals which open each episode show a man in a suit, spiraling down, out of control. The theological term would be "fallen."

During the week leading up to the final episode, I found myself being concerned -- no, no, don't let anything bad happen to these people I care so much about! The series had already been strewn with corpses: among others, Lane Pryce, a junior partner, hangs himself, as does Don's half-brother Alan; Ratchel Katz dies of leukemia; Bert Cooper, the voice of wisdom in the company, dies of undisclosed causes, and in one of the most affecting episodes, appears as a ghost to Don, singing, "The moon belongs to everyone/The best things in life, they're free." Don finally understands these words in the last episode.

Don drops out of McCann-Erikson, the advertising agency that swallowed his own agency, and he drives from place to place in California, with no plan or purpose. He is devastated when he learns that his former wife is dying of lung cancer. It doesn't occur to him that the Marlboro man has anything to do with this. Eventually he finds himself, strangely enough, in a hippie retreat center, one of those "let it all hang out" places of the '70s. In wrenching emotional pain, he makes a ragged phone call to Peggy. She is furious because he up and left without notice, but tells him, "Don, you can come home."

"I'm not the man you think I am," he says.

"What have you done that is so wrong?" she says, trying to comfort him. She is conscious of the string of mistakes and mishaps in her own life.

Don says, "I broke all my vows. Scandalized my children. Took another man's name and made nothing of it." He tells her he is sorry he never said goodbye.

Suspecting that he is suicidal, she says, "You should not be alone right now, Don." He hangs up before she can find out where he is.

Then one of the retreatants, a kindly older woman, invites to him to attend a group therapy session. He takes her hand, in a daze. As he listens to another member of the group agonize over his broken life, his distance from others, his inability to love and be loved, Don understands that he is this other man. Don drops his "cool," crosses the room in a spontaneous and heart-felt gesture, and holds the sobbing man in his arms. Don weeps, too, not just for this man he holds, but for himself. In the last scene, Don is sitting in a yoga posture with a group on a grassy plain, chanting Ohmmmmm, Ohmmmmm. A hint of a smile is on his face. His experience has washed him clean, and he wants to start all over, we believe. He wants to choose better values, to love better, and most of all, to be real, emotionally -- the basis for any new life he can potentially have.

Don is the tragic hero of this television morality tale -- a man who falls from a high place because of his human flaws. Classically, the tragic hero is a superior human being, but morally as vulnerable as the rest of us, thus allowing us to identify with him. The hero understands that his fate is determined by his own actions, not by happenstance. He is wounded spiritually, brought down by the very qualities that make him great -- his intelligence, his strength, his pride.

Why do we care about Don Draper? Because who has not been blinded by secrets, taken the wrong turn, hurt others who wanted to love us, neglected our family? We blunder through this world, all of us, using whatever power we can muster, to cope. Mostly, we mean well, but we do not always see clearly. We reach out for the gold ring, and find it is only brass. We continue reaching out, only to be brought down again and again, for we are our imperfect human selves, distracted by material things, giving ourselves to unworthy ends, looking for meaning in the arms of others, hoping to happen upon love somehow.

The last episode ends with a cloying Coke commercial from 1971, "Buy the World a Coke," a multicultural song fest starting "I'd like to buy the world a home and furnish it with love," and ending with the well-known tag, "It's the real thing." Besides filling billions of customers in over 200 countries with empty calories, Coca Cola has been accused of exploiting labor in countries such as Columbia, China, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and Turkey; aggravating water scarcity in poor countries; monopolistic marketing practices; supporting apartheid in South Africa; pesticide contamination. Coke is the real thing, all right -- it is the quintessential company of its kind, an oversized behemoth representing the soulless consumer culture.

Thank you, Matthew Weiner! Our tragic hero does not die -- compassion wins out, and Don Draper gets another chance. As part of that final phone conversation, Peggy asks Don, without the least bit of irony, "Don't you want to work on Coke?"

"I can't," he says. And thus begins his redemption.

Marilyn Sewell is the author of a new memoir, "Raw Faith: Following the Thread."