"Did you go to the Beyoncé place? Did you even do anything in Marfa?" -- Concierge at the Camino Real hotel in El Paso, January 2015. Image via Tumblr.

When we love something we inevitably ruin it with our enthusiasm. The pleasure turns passé, the charm fades, we move on to the next shiny thing. Marfa, Texas, is a city on the brink of proving this rule. For those new to Marfa: it is a beautiful, odd, art-filled place at the western edge of Texas, three hours from the nearest airport. This is only its latest incarnation. Starting in the late 19th century, it was a rail stop for oilmen, then a watering hole for ranchers. Today, because of a man named Donald Judd, local Marfans are losing ground to transplants from New York City and Seattle, the kind of people who thought they’d never set foot in Texas.

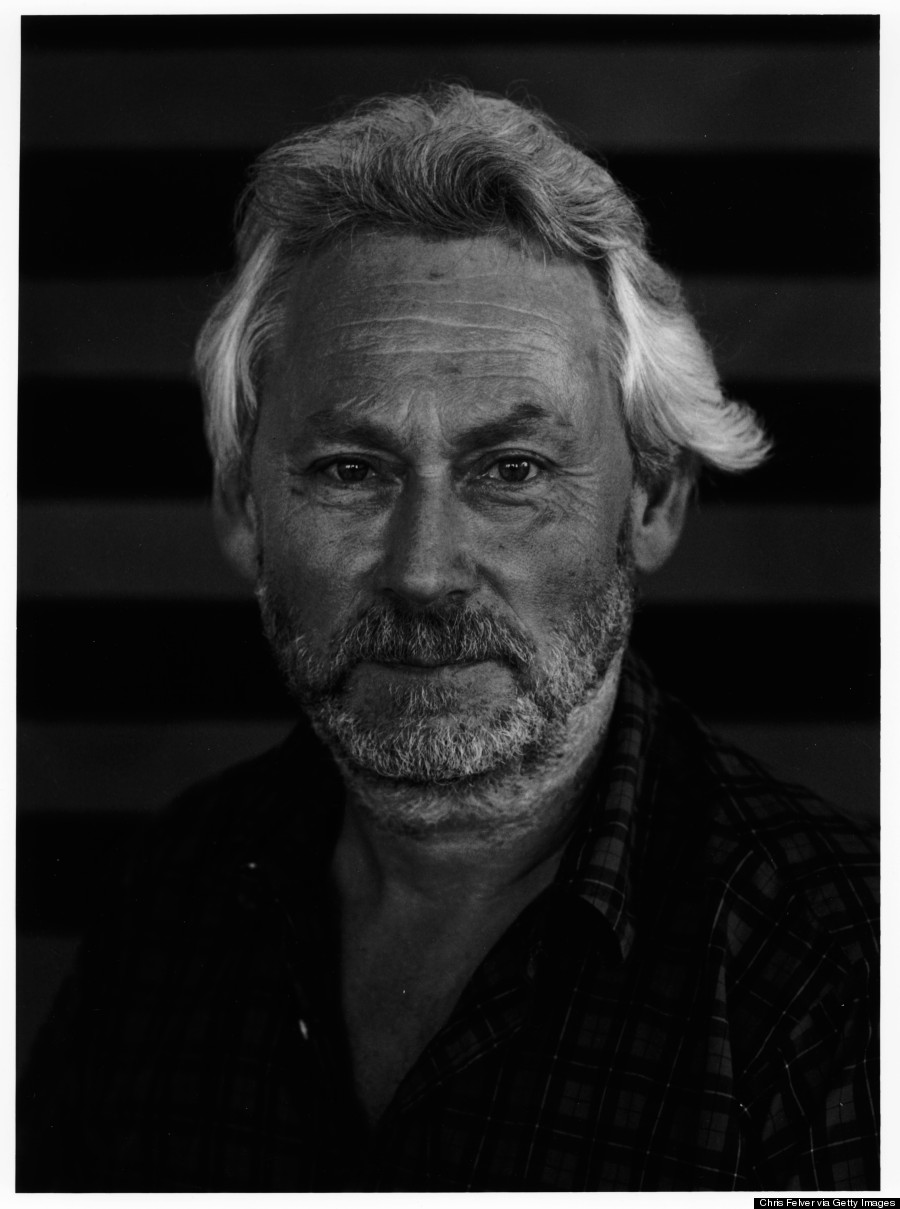

Judd, a native of Missouri, died of cancer in 1994. But his legacy lives on in the one-stoplight city he made his home. An artist who came to define American minimalism, he left the energy of early 1970s Soho in search of an asset he considered better than paint on a flat surface: in his words, “actual space.” He was a doer and a thinker -- an artist who started his career as an art critic. He looked like a slimmer, kinder Hemingway. Perennially bearded, shimmering between sleek and gruff. The type who could build a table and just as easily analyze its aesthetics.

A portrait of the artist himself, the late Donald Judd. (Getty)

For all his interest in the wild, Judd liked order. When he died, he left behind rules, on how and when the rest of us could interact with his work. These strictures are upheld by the two foundations that control his work: the Chinati Foundation, which oversees some of Judd’s Marfa properties, and the Judd Foundation, handling the rest from an office in Manhattan.

Questioning Judd’s authority as carried out by these institutions can result in comic unpleasantness, as if you’ve insulted Ronald Reagan around Sarah Palin’s dinner table. On a recent trip to Marfa with my husband, the misstep came within the first hour, during a tour of Judd’s home and studios run by the Judd Foundation.

Our mistake was using that catch-all for structural art, the word “installation.”

“The 'i' word,” our guide corrected us. “Judd never liked to say ‘install’ or ‘installation’ when talking about his work.”

The extent to which this was true was staggering. When later in the tour my husband casually asked if Judd had installed the windows in the studio himself, the response he met was silence. “I mean put them in himself,” he stumbled, trying to make things right. After all, what other word was there to use?

The guide did not seem sympathetic. “He did nothing himself,” he replied stonily, his eyes already searching for someone else to call on.

The wire image that launched a thousand travel section profiles. (AP)

The irony, of course, is that Marfa’s appeal was always its edge-of-the-planet vibe. Today, what with all the protocol, one can end up feeling incredibly observed.

Intense media scrutiny has contributed to this illusion, making Marfa seem less the middle of nowhere than the center of the universe. It started in earnest in 2005, with the opening of Prada Marfa, a photogenic fake store stocked with actual Prada shoes, by the Scandinavian art duo Elmgreen and Dragset. Increasingly, new restaurants, hotels, and creative personalities are scoring column inches.

A traveler checks into El Cosmico, a modern-day kibbutz in Marfa that epitomizes the city's desert-chic brand, complete with $200 moccasins in the gift store. (Flickr)

The hermetic sensibility is buoyed by Marfa’s changing demographics. In recent years, real estate has become prohibitively expensive for longtime locals, turning the tiny city of some 2,000 residents into something closer to a ritzy suburban enclave for the world’s wealthy. Relentlessly rising property values have led reporters to troop in. Their assessment: police officers, teachers -- those workers who run a society’s critical, if unglamorous, machinery -- are moving out, even as wealthy New Yorkers settle into second homes.

In this brave new world, European art hounds mingle with Austin good ol’ boys and girls vaguely aware that Marfa is a party. The latter are rarely there for Judd. On the grounds of El Cosmico, a hippie campground with enough cachet that Beyoncé stayed there during a much-Tumblred tour of the region, I found a couple who confessed to knowing nothing about Judd. They were visiting for the energy, and that was all.

Judd's legendary sequence of concrete blocks, on the Chinati property south of Marfa city center.

If there is a poetry to this expansion, it's that Judd loved imperfect multiples. His signature works riff on a concept -- rows of aluminum boxes each cut with unique angles, or a line of rods sized by the Fibonacci sequence. In Marfa too, every new attraction channels the last, while changing the spirit of the whole enterprise ever so slightly.

It happens: Tourism swallows, ouroboros-like, the original mystique of a place. Judd wouldn’t have moved to this Marfa, but he might recognize its shape. Within his lifetime, Soho too turned from a no-man’s land, to an artist’s haven (under his watch), to a retail juggernaut. Indeed, Judd could have been describing Marfa when he wrote during the christening of Soho of a likely future: “tourist shops and restaurants, bad art and high rents.”

And yet, Marfa is still a wonder. Above the scrub of cactus and waves of grass are the improbable galleries and restaurants -- so spare and low you could mistake them for the adobe homes common to the region. Higher still rise elegant municipal buildings befitting a legislative capital (Marfa is the seat of Presidio County). A picture-perfect courthouse dolloped in cupolas contrasts with a block of bleached art deco buildings that form the square, each embellished with only a few colorful tiles. All of it shifts under the miracle that is West Texas light.

The exterior of the Ballroom Marfa, an art, music and cinema center founded in 2003.

Marfa is emblematic of the West: cattlemen, artists, and soldiers have all gotten what they needed here. Part of its usefulness to Judd came in the form of its many disused buildings of warfare, where for much of the last century the federal government had stored the stuff of war, from weapons to German prisoners.

Judd converted two such artillery sheds into window-walled galleries now overseen by Chinati. Together, they hold 100 boxes made only of milled aluminum, each about the size and shape of a small kitchen island. The works are untitled, as are most of Judd’s. But of all his works, the boxes are truly unforgettable. They embody the twisted simplicity of minimalism, what the composer Philip Glass (who once played a concert in Judd’s Soho loft), calls “a binary way of thinking.”

Each box looks whole. Approach any one and the hidden design reveals itself -- a cube of mass scooped out of the top, a triangle of space etched into the side. Our guide, John, a second generation Marfan who fell into the job for money, found himself transfixed from his first day by the “floating” boxes, cut such that the cube itself seems to outline a small, dense one.

The effect of this patterned randomness is akin to experiencing a composition by Glass himself, who is notorious for intercutting unceasing blocks of repeated notes with sudden, new notes. Lulled into a state of expectation, your senses jump at variation.

Judd outsourced the actual creation of the boxes, as he did much of his large work, to a construction firm in Connecticut. The outer dimensions are standard -- 41 by 51 by 72 inches -- but the designs his own. Shameless mass production was one way to reject what had come before. Formalized sculpture was the enemy. Retaliating against the European churn of nudes, he lassoed light into silvery cubes.

There's no telling how this photo, obtained via Flickr, got approved.

It can all feel like magic. With each step, a few of the boxes seemed to disappear, an illusion brought on by the play of light. The windows were like boxes too, holding ribbons of grass and sky. In the distance stood a trail of concrete blocks also by Judd, sentinels at the edge of his kingdom.

He had harnessed the elements. An irresistible urge to share washed over me, via Facebook, Instagram, whatever means might get people here, no matter the consequences. Who cared about high rents? Judd made a place meant to be seen.

But Chinati rules prevailed: no photographs.