Several years ago it dawned on me that most all of my spiritual heroes are unabashedly ecumenical: Father Henri Nouwen, Brother Roger of Taize, Sister Joan Chittister, Father Richard Rohr, Thomas Merton, Parker Palmer, Wendell Berry. If you read their writings, you'll find themes of radical inclusivity, radical compassion, and radical identification. Each in his or her own way points to a God that includes everyone, loves everyone, and identifies everyone as his beloved.

This is undoubtedly a large portion of why so much of the popular religious discourse in western Christianity is troublesome for me. It so often displays God as exclusive, callous and divisive.

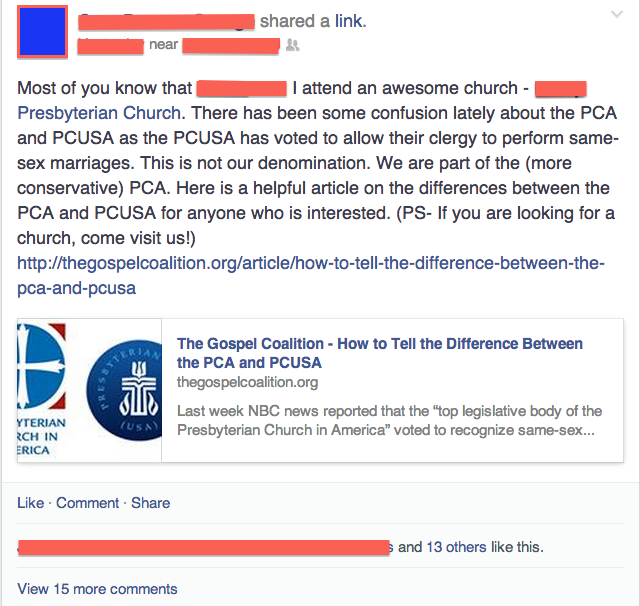

Recently, a long-term, close friend of mine whom I very much respect posted this to Facebook:

I was distressed by the post and remarked as follows:

To this, a number of commenters noted the importance of their doctrinal beliefs and the importance of differentiating themselves from others who don't hold those beliefs by making these sorts of lists, and a few even quoted scripture and lauded Jesus Christ as being a fellow list-maker (Matthew 25:31-46).

I sincerely believe this tendency is misguided, and is responsible for so much of the lack of "good news" in western Christianity's portrayal of the message of Jesus Christ.

It is driven primarily by the fear associated with this basic-most assumption:

You are in right relationship with God based on what you believe about God.

And this logically outflowing corollary:

If you don't believe the right things about God, you are not in right relationship with God.

When asked why these assumptions are so foundational, most folks will cite Paul's invocation of Abrahamic faith in Galatians 3:6. "Abram believed the LORD, and he credited it to him as righteousness."

In so doing, well-meaning persons conflate "believing God" for "believing things about God," and doctrine becomes a way to setup and defend boundaries, to rule themselves "in" and others "out."

This is tribal religion.

Father Richard Rohr differentiates this from a truer religious experience, which he says is"not something accessed by the left brain, but by the whole brain -- right and left--and the heart, body, and soul. It is an intuitive grasp of the whole. God is the heart of everything. When you say you love God, you, in fact, are saying you love everything. And that's why [tribal] religion is an inauthentic God experience. [It] becomes an excuse for not loving a whole bunch of things. That's why mystics can love their enemies, can love the foreigner, can love the outsider. They don't make these distinctions that low-level religion does. Low-level religion is more tribal, a social construct to sort of hold my group together...This is just group belonging. This is not a mystical experience."

The great tragedy is that "the word doctrine...actually means a 'healing teaching,' from the French word for 'doctor.' The creeds, as doctrinal statements, were intended as healing instruments, life-giving words that would draw God's people into a deeper engagement with divine things" (Diana Butler Bass, Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening). In this sense, much of the execution of western Christian doctrinal belief fails to pass the real-life litmus test of its own namesake. As Butler Bass goes on to say:

When creeds become fences to mark the borders of heresy, they lose their spiritual energy. Doctrine is to be the balm of a healing experience of God, not a theological scalpel to wound and exclude people.

It isn't that understanding what one believes about God isn't important, just that it is not the only task of the spiritual life. And to the extent that it is important, it is only so at the beginning.

After all, there is a level at which this mortal coil is insufficiently equipped to truly know all there is to know about God anyhow, as the prophet Isaiah remarked, "Truly, you are a God who hides himself." Paul later echoed this sentiment in Romans 11 when he said, "Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out!"

I'm always awestruck at Christians who practically oppose this reality, seemingly believing they have God all figured out! What we believe about God shifts over the course of a lifetime as we grow in wisdom, understanding, and experience of him.

Truly, which one of us has not thought one thing about God in our youth and another in our adulthood? What's more, which one of us has not seen a divorce between what we profess to believe about God and what our lives indicate we believe?

Last year my spiritual director asked me very bluntly, "Ryan, is God good? And before you answer, I don't want to know what you 'believe.' Practically all evangelicals are indoctrinated to 'think' God is good. Instead, I want to know, in your experience, is God good?" I had to answer that to my chagrin, I often only experienced God as good in hindsight, and even then, only intermittently.

Surely, I'm not alone.

So, this shifting over time, and this dichotomy between professed orthodoxy and lived orthopraxy ought to suggest that our beliefs about God may be important, but they are also perilously unstable. Living our life as if they are the primary indicator of our spiritual state is inaccurate and unwise. Making them the judge, jury, and accuser of the spiritual state of others is great spiritual folly.

Instead, we should hold our doctrines loosely and with open hands. And we should recognize that there is something much greater at work than we could possibly comprehend anyhow. God has much more in store for us than helping us to align our thinking about him into some sort of systematic theology.

Knowing what you believe about God is fine, but it isn't the same as believing God.

If we wish to grow beyond spiritual adolescence, to truly "believe God," there is no need to constantly affirm our own identity, our own group membership, or our own gender and sexual identity, and there is no need to constantly question that of others.

We can dispense with the insatiable, narcissistic need to mark ourselves "in" and others "out." We can just get on with living from the place of "in," and we can let others do that too.

"Often we think that to witness means to speak up in defense of God. This idea can make us very self-conscious. We wonder where and how we can make God the topic of our conversations and how to convince our families, friends, neighbors... But this explicit missionary endeavor often comes from an insecure heart and, therefore, easily creates divisions. The way God's Spirit manifests itself most convincingly is through its fruits: 'love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trustfulness, gentleness and self-control' (Galatians 5:22). These fruits speak for themselves. It is therefore always better to raise the question 'How can I grow in the Spirit?' than the question 'How can I make others believe in the Spirit?' --Henri Nouwen, Bread for the Journey: A Daybook of Wisdom and Faith