WASHINGTON -- On Monday afternoon, South Carolina’s Gov. Nikki Haley called for the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the statehouse grounds in the wake of the murder of nine people at a historically black church in Charleston.

Surrounded by lawmakers from her state -- black and white, Democrat and Republican -- Haley said she would demand a special session of the legislature if needed. Her statement was hailed as a turning point. Should the flag come down, it would mark a stunning shift in the politics of this issue. Recent history is filled with lawmakers who have touched the flag powder keg only to have it explode.

One of the first, if not the first, to suffer that particular burn was Zell Miller, Georgia’s former senator and governor.

Long before he became infamous for accusing Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) of wanting to arm the troops with spitballs -- and challenging news host Chris Matthews to a duel -- Miller was a Democratic governor hoping to leave his mark on civil rights. He went after the Confederate flag. It nearly ended his career.

“Miller used to say this: 'I cannot call myself a progressive Southern governor if I’m not out front on changing the flag,'” his former chief of staff, Keith Mason, recalled in an interview on Monday. “He was the forerunner of it. And he paid a big price for it.”

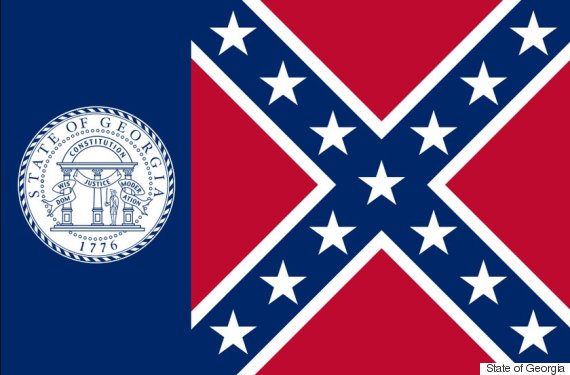

In May 1992, Miller announced his desire to remove the "Southern Cross" of the Confederate battle flag from his state’s banner, which had only begun incorporating that imagery in 1956. "What we fly today is not an enduring symbol of our heritage, but the fighting flag of those who wanted to preserve a segregated South in the face of the civil rights movement," he declared.

Miller had his own rocky relationship with the civil rights movement, having backed integration at the University of Georgia but also having run on anti-civil rights platforms earlier in his career. His intergovernmental relations director at the time, Ed Kilgore, said that this history “always aggrieved him” and that by going after the flag, he was trying to make amends.

But Miller was also compelled by a desire to clean up the state’s image before the Olympics came to Atlanta. “We were all about not having this lingering around during 1996,” said Mason.

Miller wasn’t jumping on this grenade alone. He had the support of some political heavy hitters. Paul Begala, a longtime Democratic operative who worked for Miller and then-presidential candidate Bill Clinton, said Clinton backed him, hopeful that Miller's effort would advance the same theme being pushed by Clinton and running mate Al Gore -- of thoughtful, modern Southern Democrats. Miller, according to Mason, also had the backing of Newt Gingrich (aiming to become speaker of the House) and Jack Kemp (the Republican vice presidential nominee in the next election).

But there were ominous signs too. Begala recalled a focus group they ran to gauge the public’s support.

“I distinctly remember one guy saying, ‘This is ours. This flag is ours. It is our symbol and aren’t we entitled to something? They parade around Atlanta in their native garb and we can’t even have our flag?’” To this day, Begala isn’t sure what, exactly, the man meant by “native garb.” But he said the “open, overt hostility for black people was very powerful.”

“It was one of the most upsetting pieces of political work we did,” he said.

It wasn’t just white Georgians who were opposed. Several African-Americans in the focus group just didn’t see the value of raising the issue at that point in time. The state’s political establishment wasn’t persuaded either. State House Speaker Thomas Murphy, a Democrat, said he “personally” didn’t see “anything wrong with the flag we have.” Later, he claimed that 95 percent of his constituents were opposed to a change.

Miller was stung but not defeated. He decided, to the disapproval of a number of his aides, that he would make the flag a major focus of his State of the State address in 1993. He also decided he would be aggressive in his delivery, directly calling out the opposition for finding easy comfort in settled, old views.

“It really surprised a lot of people,” recalled Kilgore, who co-wrote the speech with Miller. “There was a passage at the end -- and this was Zell’s doing -- based on To Kill a Mockingbird, where he called out legislators for perpetuating this. He suggested that it was easy to do this in a mob but not as individuals. ... The original draft of the speech he actually named names. We talked him into not naming individuals but groups of people.”

The speech would resuscitate the flag debate, but it wouldn’t save it. In early February 1993, about 250 people came to the state capital -- many dressed in rebel gray uniforms -- to march in support of keeping the Confederate imagery. The Georgia legislature, meanwhile, didn’t budge. Bleeding support among rural white voters, Miller was desperate to move on to a separate measure to direct state lottery revenue into education before his re-election bid the next year. He let the flag debate die.

“He was the dominant figure in modern Georgia politics,” said Begala. “The only person I’d rank up there is Bill Clinton in terms of political talent. And it was still more than he could do.”

Miller would win the 1994 election but by a margin that was far closer than it might have been. It would take another seven years for Georgia to address the flag issue again.

In 2001, then-Gov. Roy Barnes, another Democrat, moved to minimize the state flag’s rebel insignia. Unlike Miller, however, he did so discreetly. One Wednesday, the state House Rules Committee introduced a redesign that featured the state seal; beneath the seal was a banner with the images of the 1956 flag and several other U.S. and state flags. That same day, the House passed it by a 94-82 vote. The Democratic-controlled Senate followed with a 34-22 vote.

“It was LBJ-style horse trade politics,” Mason said of Barnes’ backroom maneuvering. “He dealt with it more with a surgical knife. He quietly built the case with the business community and some legislative leadership and others behind the scene.”

It wasn't all done in secret. Barnes would give an impassioned speech after the House Rules Committee passed the bill, defending his roots and explaining his position.

"My great-grandfather was captured at Vicksburg fighting for the Confederacy, and I still visit his grave in the foothills of Gilmer County," he declared. "But I am also proud that we have come so far that my children find it hard to believe that we ever had segregated schools or separate water fountains labeled 'white' and 'colored.'"

Once again, criticizing Confederate symbols would prove politically costly. Barnes was defeated in 2002 by Sonny Perdue, a Republican, who ran in part on holding a referendum on the flag.

''There was this huge undercurrent of resentment and anger about the flag, but I think we all missed it because it's not something people discuss in the open,'' Merle Black, a political scientist at Emory University in Atlanta, told The New York Times.

When he took office, however, Perdue went quiet on the matter. Black civil rights leaders and unions threatened to boycott the statewide flag referendum. Corporations suggested that they’d hesitate doing business in Georgia if the Confederate flag was brought back. In April 2003, state lawmakers and Perdue struck a compromise. Georgia’s flag wouldn’t include the evocative emblem of the Confederate battle flag. But it would be based on another Confederate flag, nicknamed the "Stars and Bars."

That compromise remains to this day.

As South Carolina now grapples with what to do about the flag flying over its statehouse grounds, Georgia's experience of the mid-1990s certainly provides cautionary lessons. But former aides to Miller suggest that his fate will not be Haley's and that the road to success has likely been paved by the changing mood of a country and a state trying to do right in the wake of a horrific racially motivated murder. Miller was a “trailblazer” as Mason put it. But as Begala noted, he would likely have succeeded had he simply been governor some 20 years later.

“It is a different time. It is the changing demographics. It is what’s called cohort replacement. Grandpa dies and grandson takes his place,” Begala said. “I believed then and now that the arguments in favor of the flag were unsustainable historically and morally, and when something is unsustainable, over time it will end.”

Want more updates from Sam? Sign up for his newsletter, Spam Stein.