"Orange, Hat & Grace" by Gregory S. Moss is a clever, funny, sexy play about the psychological state of a bright, isolated older woman.

Imagine an image you have never seen on a stage, now write it there -- a common playwrighting exercise designed to liberate. After dismissing unicorns playing backgammon and sets made entirely of toast it can have some interesting results.

Old woman with graying hair has sex with wild abandon on kitchen table. Young man has a fully convincing shave. Girl claws her way out of earthen ground. Gregory S. Moss's bright, brave new play abounds in unique imagery and wily psychological wrangling.

Soho Repertory Theatre's brilliant Artistic Director Sarah Benson has conjured a sensual Gothic fairytale playing chords of sex and death with a dexterous and humorous touch.

Orange is an older woman alone in her cabin in the wilderness. She tries to be civilized; she reads, she cleans, but she can't deny the wild woods encroaching on her doorstep. Hat, a robust energetic young man, announces himself by tearing wood off her roof to make his fire, as he will later tear strips off her in other ways to ignite his own life force. A connection is made. Not based on love, but on need. However, the haunting presence of a feral young girl (Grace) penetrates their domestic perimeters to deadly effect.

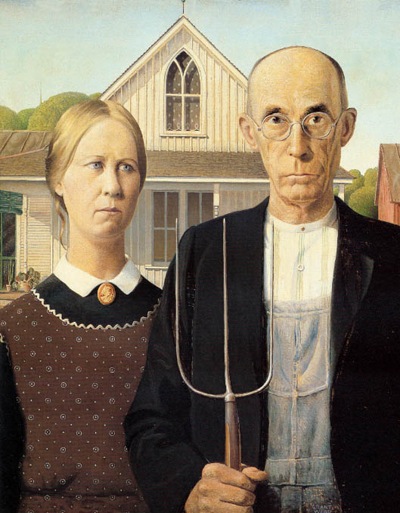

--American Gothic by Grant Wood

Gregory S. Moss in conversation says the nature of Tragedy is having to make a choice, and then facing its consequences. Even here, away from the eyes and judgments of most, Orange wrestles with the rightness and guilt of her choices as a woman: mother, homemaker, educator sexual creature. As Moss says, "a puritan ethic clashes with our natural scatological inclinations." The sound of that clash is hypocrisy, and hypocrisy is funny. Squaring the tragic-comic circle.

We sense depression and deprivation, and see Appalachianesque isolation, but Moss has set his play less in a literal context, more a rich psychological landscape. Glowing bulbs in the trees have the feel of the souls of the lost, emotional wounds are inflicted and wild birds drop dead from the sky, as an old woman's limbs start to buckle the bark of the trees outside starts to rot.

With visual resonances of Grant Wood's American Gothic, and the world of Walker Evans, the play is inspired by the musical motif of the Murder Ballad: a traditional melancholy refrain with practical morality. We hear the mechanical hum of the old 78 turning with the lamenting strains of early Country Blues: The Carter Family, Charlie Patton, Mississippi John Hurt.

Moss explores a range of expressive sound and language from the grunt "like a one legged goose dying in the grass" to elegiac prose and incantation.

Death approaches the old woman like the black night outside her cabin and her attempts to brush it back are futile. In the face of defeat life fights hard with its strongest weapons: sex, love, memory, loss. A triptych of reality is at work: the whole play could be a dream by the fire with the other two characters representing part of Orange's mind, her ephemeral beauty lived out in Grace, her strength and humour in Hat. The two are phantoms from her past: daughter, lover, as well as being living characters themselves.

Rachel Hauck's imaginative set is breathtaking, specific, poetic, and Matt Frey's perfectly delicate lighting design shimmers off black gloss walls. There are excellent performances from all actors: Stephanie Roth Haberle brings deep courage and dignity to Orange, Matthew Maher is a resplendent rambunctious Hat.

A slick modern swipe at a fable, the bare bones of Erskine Caldwell's "Tobacco Road" meets the dark treacle of Martin McDonagh's "The Pillowman." Moss reminds us of a time when family were who you lived by, a fate given group who helped you save yourself by hard shared mutual labour, totally without the modern concept of scrutinised relationships. Yet his simple cabin in the woods is as full of dreams, pain, secrets and possibility as the Soho street outside.

At the end of the play Hat's suggestion that the three characters link together causes a moment of deep crisis for Orange. How modern that seems, the very idea of facing the people who have shaped our lives the most can feel more terrifying than any ghoulish ghost story.

An echo found in an English poem "The Old Fools" by Philip Larkin (1973):

Perhaps being old is having lighted rooms

Inside your head, and people in them, acting

People you know, yet can't quite name; each looms

Like a deep loss restored, from known doors turning,

Setting down a lamp, smiling from a stair, extracting

A known book from the shelves; or sometimes only

The rooms themselves, chairs and a fire burning,

The blown bush at the window, or the sun's

Faint friendliness on the wall some lonely

Rain-ceased midsummer evening. That is where they live:

Not here and now, but where all happened once.

This is why they give

An air of baffled absence, trying to be there

Yet being here. For the rooms grow farther, leaving

Incompetent cold, the constant wear and tear

Of taken breath, and them crouching below

Extinction's alp, the old fools, never perceiving

How near it is. This must be what keeps them quiet:

The peak that stays in view wherever we go

For them is rising ground. Can they never tell

What is dragging them back, and how it will end? Not at night?

Not when the strangers come? Never, throughout

The whole hideous inverted childhood? Well,

We shall find out.

Lily Bevan is nominated for a 2010 Off West End London Theatre Award for Best Director