Philip Roth reads at the 92nd Street Y on May 8, 2014 (photo © Nancy Crampton 2014, all rights reserved, and used with permission)

The 92nd Street Y's Kaufmann Concert Hall is usually a sedate place to go for a reading or event: pleasant lobby, wood-paneled calm, comfortable seats, the names of great thinkers and writers from Moses to Dante to Jefferson rimming the room. However, last Thursday, May 8, it was full of nerves and excitement. Most of the audience members were not young, but it felt more like a rock concert than a literary reading. People scurried out once seated, not for more drinks at the bar but for more books at the Bloomsday Books table: Every copy of Philip Roth's books had been taken to the author's New York apartment weeks in advance and signed before being brought here.

Roth had been scheduled to read at the Y back in October 2013, in a joint event with Claudia Roth Pierpont (no relation, but she's the author, with Roth's cooperation, of the new critical study Roth Unbound: A Writer And His Books). The evening was postponed, and many people there last Thursday night couldn't believe Roth was actually going to appear, and read, this time. The couple seated next to me, tourists from Liverpool who had gotten tickets through their hotel, were murmuring to each other as nearly an hour had passed and there was no sign of Roth. Much was being said of him, though. Pierpont began the evening with understanding, often funny, words on Roth's female characters. Nicole Krauss read a long letter she'd written Roth and spoke on what he means to her and her own writing. And then, finally, there he was.

I met Roth at lunch a decade ago, and though I won't write about that lunch, what I took away from it was twofold: his easy, gentlemanly elegance and his remarkable, clear-eyed view of American history, about which he spoke with depth and great humor. Both these things were front and center at his reading at the Y. Roth took the stage in his own time, sartorially splendid in black, smiling. Passing by the lectern his two introducers had used, he sat behind a heavy, carved desk. He let the crowd clap and cheer for a moment and then waved his hand. Instant obedience, and silence.

The sections Roth chose to read were both from Sabbath's Theater (1995). He introduced the book first, politely not assuming people there had read it, although I expect most of us had, by giving its historical context and summarizing the plot. Sabbath's Theater is a saga of sex and death, gory happy couplings and underwear theft and funerals, the visiting of graves, illicit Polaroids, and fishing. For all its rampant ribald humor, the plot of the book is a burial plot, the story of Mickey Sabbath, our now middle-aged narrator, and of his big brother, Lt. Morton Sabbath, beloved son and brother, killed in action at 20 in the Philippines on Dec. 15, 1944. Roth chose to conclude his reading with Mickey's visit to the rainy, watchdog-guarded "burial ground established in the early days by the original seashore Jews." Roth began the grim trip with a grin, and he read out the lines "Jews guarded by dogs? Historically very, very wrong." As the laughter subsided, the history took hold. The litany of the dead; the discovery of Mickey's grandparents, Clara and Mordecai. Mickey never knew his grandfather, but oh, he remembers his grandmother, and he talks to her. When he and Morty go fishing for the last time ever, Grandma is no longer there at the seaside but here in the cemetery. She cleaned and cooked the fish for the boys, once upon a time, at the family feasts on the Jersey shore: "Never cut off the head and the tail. Baked it whole. Baked bluefish, corn, fresh tomatoes, big Jersey tomatoes. Grandma's meal." As Roth mentioned the Jersey tomatoes, he smiled broadly, and I wanted to bring him a basket of them, just as they were in 1944, just as they still can be, out in the far reaches of the place once unironically called the Garden State.

As Roth read of Mickey remembering young Sonia Gindi, a "little hairy fireplug" of a Syrian Jewish girl, he half shook his head, then joined in the audience's laughter. Though Sonia's brother Isaac is terrifying, Mickey can't help himself: "But I was twelve, inside my pants things were beginning to reverberate, and I could not keep my eyes off his hairy sister." In a moment, in a sentence, everything changes again, and the laughter stills. "But then came the war. I was thirteen. Morty was eighteen. Here's a kid who never went away in his life, except maybe for a track meet. Never out of Monmouth County. Every day of his life he returned home. Endlessness renewed every day. And the next morning he goes off to die. But then, death is endlessness par excellence, is it not? Wouldn't you agree?" The family humor of a grandson reflecting for his grandmother, at her grave, upon "the devouring frenzy of you and your dentures and the repugnance this ignited in my mother" plays happiness against disgust, life against death: "The interplay, the ridiculous interplay, enough to kill all and everyone."

Roth's reading and its reminiscences were beyond vivid and vital, shattering that cemetery setting and filling it with Jersey shore sunlight. You could see the surf on that beach, the boys casting, the flip and shine of the big fish. See Grandma cleaning those fish, taste the oily flesh, hear her dentures as she worked on that corn. Most of all, you could see right there in front of you a writer enjoying, many years later, what he had made and was reading -- genuinely, without superiority or smug satisfaction. If anyone in the world of letters is entitled to feel superior or smugly satisfied, it's Roth. Yet as he read you saw not a shred of anything but affection, humor, and fond memory. He was having a good time up there, the founder of the feast, and also part of the audience.

Roth's reading brought tears to anyone who has buried someone beloved. Yet what flowed from it was nowise morbid or even poetically elegiac. Nostalgic, yes, for the eighty years just past, but realistic about them too -- and above all historic. No American writer of fiction in this present day has half as keen a sense of, appreciation for, and respect for history as does Roth. His novels never smell of footnotes; they just feel right. He was there, and that's the way it is.

Roth announced in 2012 that he has given up writing fiction. After his reading at the Y, Roth reportedly told guests there that he has made his last public appearance. These two things are perhaps like retiring from work for anyone. May Roth never give up those things his writings intimate he really loves -- from baseball games to time in the country and walking the streets of the Upper West Side with good friends to Zabar's to those Jersey tomatoes -- and may he have very many years to enjoy them now without the massive responsibility of us.

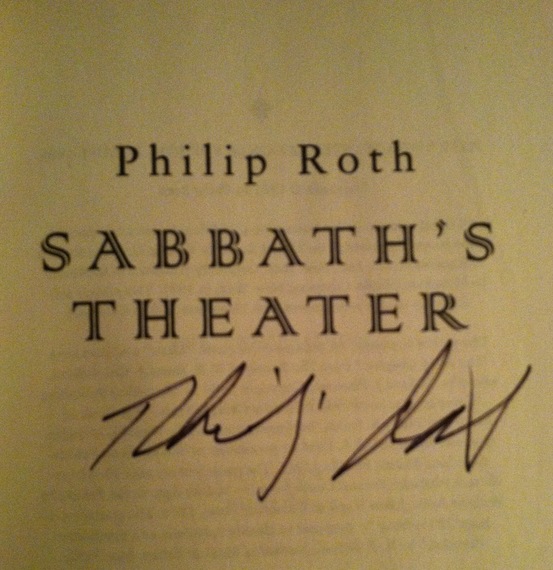

My copy of Sabbath's Theater

For more on Anne Margaret Daniel, visit annemargaretdaniel.com.