"Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it," George Santayana once famously said. A country with no sense of history has no future, because it is the remembrance of the past successes and failures, which undergirds a collective sense of purpose and provides a roadmap for nation-building.

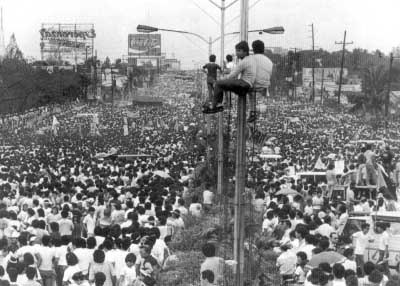

Three decades after its world-historical 1986 "People Power" uprising, which inspired similar non-violent revolution across the world, the Philippines is still struggling to anchor itself on a unifying narrative of nation-building. The Southeast Asian country is still searching for its place in history. Nothing symbolizes the Philippines' confused state of mind better than the fate of the the Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA).

As far as its historical relevance is concerned, it is perhaps comparable to Bastille (and its place in the French Revolution), Azadi Square (for the Iranian Revolution), the Tahrir Square (for the Egyptian Uprising against Mubarak), and Tienanmen square (and its place for China's 1989 student uprising). The EDSA served as a the main theater of popular uprising against, most memorably, Marcos as well as subsequent governments, particularly the disgraced President Joseph Estrada, who had to step down in 2001 after massive outcry over allegations of corruption and abuse of power.

Today, EDSA is synonymous with traffic jam and urban mayhem -- a poignant reminder of the failures of post-Marcos administrations in providing even the most basic services to the citizenry. As Filipino historian Vicente Rafael puts it, "The memory of People Power is daily dissolved by the reality of masses rushing in disaffection, absorbed in their alienation."

Without a doubt, EDSA brought about elements of formal democracy, with constitutional guarantees of civil liberties and political rights. The 1987 Constitution, deliberately framed as an anti-Marcosian document, has employed all kinds of institutional constraints to guard against executive tyranny. Today, the Philippines has among the most rambunctious media, while ordinary citizens relish discursive freedom unmatched by any country in the region.

Along with Indonesia, the Philippines is the only liberal democracy in the whole Southeast Asian region. Yet, the post-EDSA leadership has overseen a decentralization of corruption, instead of ushering in accountability and transparency. A fairly constant proportion of (a booming) population continues to live in abject poverty, while widespread unemployment has pushed as many as 10 million Filipinos overseas.

The Filipinos got rid of a despot, but in exchange they fell (once again) victim to the very oligarchy that the Marcos dictatorship tried to tame. Frustrated over the limited developmental gains of the post-EDSA regime, a growing number of people, especially among the youth and educated, have flirted with historical revisionism and fantasies of strongman rule. A more judicious assessment, however, shows that what the Philippines needs is not a return to autocracy, but instead establishing a genuine democracy, which it never has had.

Elite Democracy

In Civil Resistance and Power Politics, edited by Sir Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash, Filipino political scientist Amado Mendoza skillfully demonstrates the limits of EDSA uprising in terms of bringing about systemic change to the Philippine society. The "people power" uprising underscored the efficacy of non-violent resistance against brutal dictatorships, inspiring students, labor unions and political activists in Taiwan, South Korea, Latin America and much of Eastern bloc to successfully depose autocracies (both communist and capitalist) across the world.

The problem, Mendoza points out, was that the EDSA uprisings largely returned the country to the pre-Marcos oligarchy, which was more interested in protecting its own privileges than promoting the welfare of a promising post-colonial nation. No wonder then, the Philippines rapidly transformed from one of the fastest growing economies in the world in the 1950s, with the second highest per capita income in the region, into a dysfunctional democracy by the late-1960s.

It was precisely the incompetence and greed of the old oligarchy, many of whom descended from favored indigenous clients of Western colonial powers, which set the stage for Marcos' dictatorship. Visionary and self-confident, Ferdinand Marcos thought (à la 'modernization theory') that democracy was not fit for a developing country like the Philippines, which had to first consolidate its nation-building foundations.

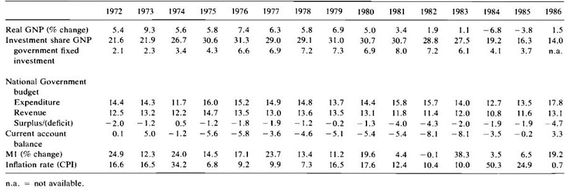

But Marcos was neither Park Chung-hee, who made South Korea a global industrial powerhouse, nor Lee Kuan Yew, who made tiny Singapore a global force. Overtime, the Marcos regime descended into a repressive and dysfunctional order defined by endemic corruption and debilitating cronyism that went along rampant violation of human rights and basic civil liberties. By the 1980s, the Philippines fell into an economic abyss, as hyperinflation, gigantic dollar-denominated debt, a free-falling currency, and a ransacked treasury exposed national misery on an unprecedented scale. (See figure 1 for basic macroeconomic indicators of Marcos regime)

Figure 1. Philippine Macroeconomic Indicators under Marcos Dictatorship

Source: Dohner & Intal 1989.

Parts of Mindanao and much of rural Philippines also fell under the spell of insurgency, threatening to shred the country into pieces. The country was a total mess. International actors, particularly America, which for decades relied on Marcos as a staunch Cold War ally, eventually sided with more progressive elements of the old oligarchy in order to prevent a communist-led overthrow of a flagging dictatorship.

The result was the oxymoron of 'elite democracy', led by an oligarchy that persistently blocked efforts at bringing about social justice and egalitarianism to the poverty-stricken country. Instead of returning power to the people, it created a political system based on a modus vivendi among the ruling families, who agreed on the primacy of electoral competition as the prime mechanism for capture of the state machinery.

A Hollow Democracy

In his best-selling book How Asia Works, Joe Studwell, a trained economist and veteran journalist, eloquently shows how the post-Marcos Philippines oversaw one of the most notoriously ineffective land reform programs in human history. Since genuine land reform means chipping away at the power of the landed elite, it is an excellent gauge of state power and the egalitarian nature of its policy.

Comparing land reform programs across post-war Asia, Studwell laments: "Nowhere in Asia has produced more plans for land reform than the Philippines. But equally no ruling elite in Asia has come up with as many ways to avoid implementing genuine land reform as Filipino one."

The post-Marcos elite also skillfully instrumentalized the mantle of patriotism to create a constitutional order, which placed all kinds of restrictions on foreign investments and market competition. This allowed them to protect their inefficient industries and monopolize key sectors of the economy.

Instead of creating a vibrant agricultural sector, so crucial to poverty-alleviation and early-industrialization take-off, and establishing a world-class manufacturing sector, so crucial to employment-generation and exports earnings, the Philippines became a service-oriented economy, with major conglomerates dominating utility, infrastructure, and retail businesses.

Today, the Philippines is among the poorest countries in Asia, with per capita incomes that are comparable to sub-Saharan Africa and landlocked nations of Latin America. It is also among the most unequal societies in the world. Recent years, in fairness, have seen rapid economic growth, but 76 percent of newly-generated wealth was swallowed by 40 richest families, the worst kind of growth-concentration in Asia.

The political institutions are equally monopolized: Around 178 political dynasties collectively dominate 73 out of a total of 80 provinces, with vast majority of legislators (70 percent) hailing from political dynasties; not even Latin American countries like Mexico (40 percent) and Argentina (10 percent) can match such level of oligarchic takeover.

No one in his right mind can call the Philippines a genuine democracy. It is an oligarchy, where elites either directly compete in elections and/or bankroll the electoral campaigns of their proxies. The Filipino voters, one could argue, are essentially glorified spectators in this clash of titanic oligarchs.

Meanwhile, the remnants of the Marcos regime, including the late dictator's family have joined the fray. Astonishingly, Ferdinand "Bong-Bong" Marcos Jr. is in a strong position to win the vice-presidency in coming elections, setting the stage for a potential Marcos comeback to the Malacanang. And he hasn't been shy with engaging in historically revisionist claims aimed at glorifying his father's legacy -- inspiring an "autocratic nostalgia" among a growing number of millennials, who have had no direct experience of Marcos dictatorship but vividly experienced the failures of its successors.

Rodrigo Duterte, a firebrand provincial mayor and a contender for presidency, hasn't also been shy with his praise for the late-dictator, even suggesting his openness to Ferdinand Marcos' burial as a national hero. Tapping into a wellspring of frustration among the Filipino people, including the (impressionable) millennials and middle classes, both Marcos and Duterte have emerged as serious contenders for the top office, promoting 'strongmen' style of leadership as the only way forward for the country. Well, as the legendary Lee Kuan Yew, who had little respect for incompetent leaders, once lamented, "Only in the Philippines could a leader like Ferdinand Marcos, who pillaged his country for over 20 years, still be considered for a national burial."

The Philippines is rapidly approaching a crossroads, given the choice between reverting to strongman leaders or, alternatively, complete the EDSA revolution by bringing about genuine democracy. We may very well discover which direction the country chooses to pursue as we approach the 2016 presidential elections.