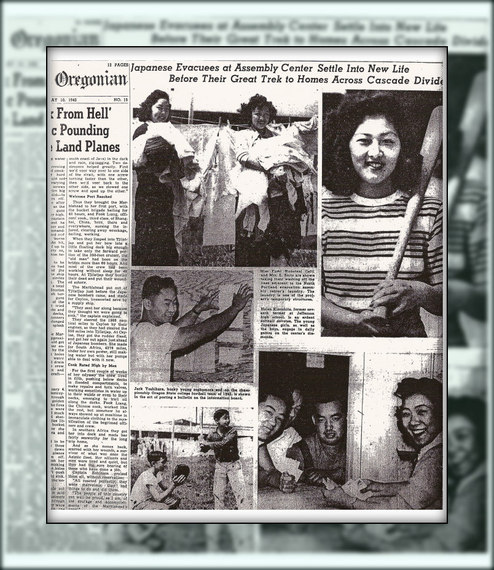

The Oregonian photo page from May 10, 1942 somehow, someway found smiling young internees effortlessly going about their daily lives behind barb wire and armed soldiers. A year later, President Roosevelt appointed the paper's editor and publisher Edwin Palmer Hoyt as director of the Domestic Branch of the US Office of War Information, the American WWII propaganda agency.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It appears The Oregonian has once again failed the surviving internees, the Japanese-American community, the city and beyond with its whitewashed coverage of the paper's role in Portland's nightmare episode of ethnic cleansing and its WWII internment concentration camp.

Writer Joseph Rose (Japanese-American internment in Oregon: Never forget February 1942, 02/19/16) claims the paper's coverage at the time was "appalling," due to its inability to ask "no hard questions. The newspaper failed to perform its basic function of fostering debate, seeking the truth and questioning authority when human lives hang in the balance."

But Rose's take doesn't come close to the awful truth of the paper's actions in this case. He describes the paper as one that basically ignored or downplayed the harrowing internments. This is false. As a result, his piece represents a continuing whitewash by this city's paper of record that did so much more than supposedly ask no hard questions.

What's really appalling is either Rose knows the truth, or he's failed to make the most basic efforts at learning the role taken by his employer in this cruel human rights chapter. Either way, his Feb. 19 article fails to recall that The Oregonian not only did ask and answer some important internment-related questions of the day, it took a leading role early on in the roundup of the Japanese-American community both through its editorial pages and in person during Congressional hearings on the internments held in Portland.

The Oregonian not only abdicated its responsibility to report objectively on the internment issue, it absolutely led the charge that every man, woman, and child with Japanese ancestry, US citizens and aliens alike, had to go. The Oregonian wasn't the watchdog questioning or not questioning authorities; it was a co-conspirator completely in bed with the powers that be.

Executive Order 9066 issued on February 19, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt set off a series of actions ultimately forcing more than 110,000 Japanese and Americans of Japanese descent into isolated military-style camps in Western desert areas for the duration of the war. Prior to their final destinations, the internees from California, Oregon and Washington State were first ordered to report to temporary Assembly Centers, a total of 16 locations up and down the West Coast, while the larger desert facilities were constructed. The Rose City ended up with the Portland Assembly Center, its very own feeder concentration camp.

"The support for removal expressed at the Portland hearings was not atypical, but the Portland hearings (of the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration - better known as the Tolan Committee) did differ from those held in San Francisco and Seattle in one important way - the absence of organized opposition," wrote historian Dr. Ellen Eisenberg in "As Truly American as Your Son": Voicing Opposition to Internment in Three West Coast Cities; Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 104, No. 4, Winter 2003. "Small but organized groups opposing the removal participated actively in the San Francisco and Seattle hearings, but in Portland no organized group defended Japanese Americans or questioned the need for mass internment."

No organized group, not one, spoke out for the Japanese Americans in Portland, according to Eisenberg.

However, those speaking in favor of removal at the Tolan Committee hearings in Portland included Edwin Palmer Hoyt, editor and publisher of The Oregonian, who provided testimony on February 26, 1942 focused mainly on the potential for sabotage by the resident Japanese Americans in regards to widespread forest fire arson. Hoyt somewhat bizarrely explained, "I want to give you a viewpoint . . . which was expressed to me . . . that 10 or 12 individuals, in the western part of Oregon when the weather is at the right point and the humidity low, and with an east wind blowing, could set a fire that would virtually destroy our entire forest area, at least the commercial aspects of it" as a threat to the nation's military need for lumber. Hoyt then submitted his paper's pro-"evacuation" editorial from that day's publication titled "For the Tolan Committee" directly into the committee's official record.

According to Eisenberg, only one person outside the Japanese-American community, Azalia Emma Peet of neighboring Gresham, a Methodist missionary who had lived in Japan, had the courage to publicly question the internments at the Tolan hearings.

The paper's February 1942 pro-removal editorial, the Tolan Committee Congressional hearings, and editor and publisher Palmer Hoyt's testimony supporting forced removal are never mentioned in Rose's article last month on the local internments and The Oregonian's related coverage.

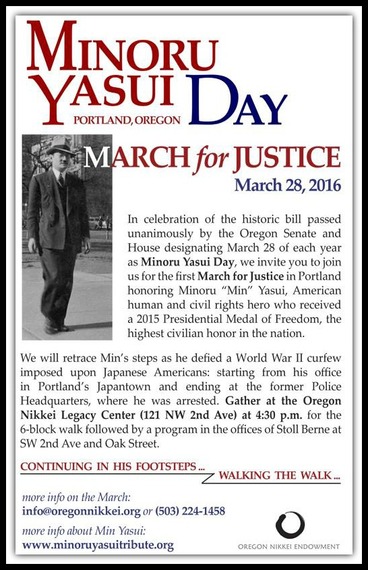

On November 24, 2015, Barack Obama presented to the family of the late lawyer and civil rights leader Minoru "Min" Yasui the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. A native of Hood River, Yasui is the only Oregonian to have received the award. He began his lifelong pursuit of human rights by challenging the wartime ethnic curfew in Portland, was jailed for months in solitary confinement in Portland's Multnomah County Jail, interned at the city's Assembly Center, and even falsely stripped of his citizenship for a time. Yasui challenged the legality of the ethnic curfews all the way to the Supreme Court, and helped direct the decades long campaign which resulted in a US government apology for the internments and reparations of $20,000 to each internee.

Holly Yasui, daughter of Minoru Yasui, recently emailed me the following:

"Though I do not hold the current City Hall or the editors of The Oregonian responsible for the actions of their predecessors, I agree that representatives of those institutions could certainly set the record straight by issuing apologies as the President and Congress did in 1988 on behalf of their predecessors."

On March 28, 2016, the first official Minoru Yasui Day in Oregon, a public march will retrace his steps from Yasui's former law office in the original Japantown district to the old Portland police headquarters in a reenactment of his trek through the night-time streets of the Rose City alone to challenge the curfew laws. Minoru Yasui Day on March 28 will remain an annual event in Oregon as unanimously approved by the state House and Senate, and signed into law by Governor Kate Brown.

One final note.

Much of the information here (and details about the equally unjust internment actions by the City of Portland and related government officials) was earlier published Feb. 4, 2016 in the Speakout section of Truthout.org, and in 2013 in Blueoregon.com, both works by this writer. I had first submitted the piece which became the Truthout article to Erik Lukens, editorial and commentary editor at The Oregonian, for publication. He replied this Feb. 1: "Lawrence: Your piece would supplant another guest opinion . . . with greater relevance and interest to our readers. Erik."

Once again, The Oregonian gets it completely wrong.

# # #

About half of the nearly 4,000 area residents who were interned in Portland from May through September 1942 before their imprisonment in the larger desert concentration camps reportedly settled elsewhere and never returned home.

One of the Portland internees who did return and lived for many years after the war was the late Harue "Mae" Ninomiya who died last October. Read my 2008 interview with Ninomiya for much more personal details about the internments.