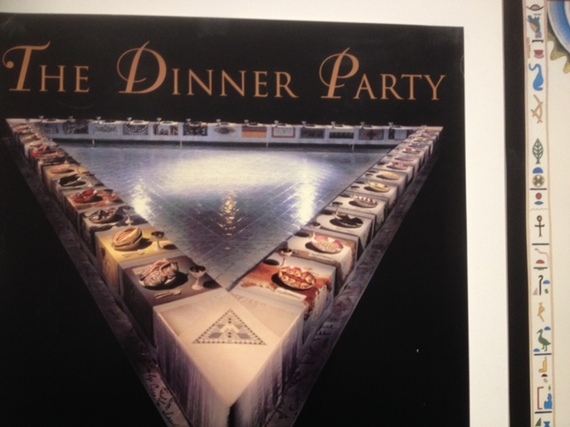

No single artist played a greater role in the era of the Sexual Revolution than a young woman born in Chicago with the name Judy Cohen who renamed herself Judy Chicago. And nothing scandalized the respectable art establishment so profoundly as her enormous ceramic and textile installation she named The Dinner Party that consisted of 39 place settings of shimmering ceramic vulvas.

Mrs. Chicago, now 76, came to Bordeaux late last winter to open the most comprehensive collection yet mounted--sculpture, paintings, ceramics and parts of the many essays she has also written across her lifetime. The Dinner Party, widely regarded as her masterwork, remained at its permanent home in the Brooklyn Museum--at 43 x 36 feet too large and too costly to ship. But two early ceramic castings from it are on display this spring at Bordeaux's Museum of Contemporary Art.

"Deficit and disobedience," she told a packed auditorium of art students and aging French baby boomers, have been hallmarks of her life and work. "Deficit," she explained, became clear to her in her first art history class at UCLA where most of the students were young women. She recalled asking the professor, a man, about women's contribution to western history. "Women's contribution to European history?" the professor responded: "They made none." From that deficit in the professor's knowledge came disobedience. "From that moment I became very disobedient: the Hell with you!"

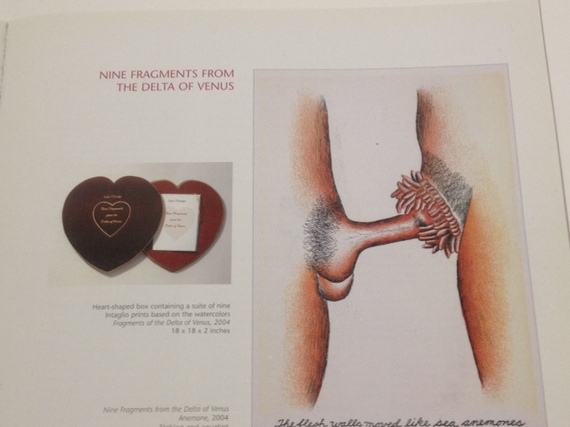

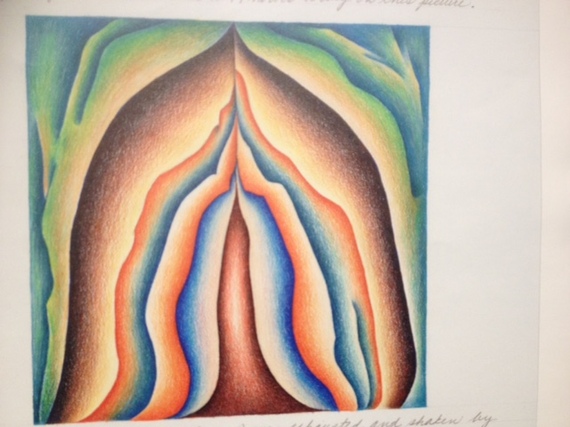

Cultural deficit--the erasure of women from the story of art and history--enraged Judy Chicago, but as the feminist and sexual revolutions advanced, and as her commitment to making art intensified, she found herself moving into a deeper deficit: the absence of female sex organs in nearly all the sculpture and painting of the human body since the birth of western art. In the face of phallic celebration and obsession, she understood how the female body had been presented as little more than a passive receptacle, its creases, depths, caverns and buttons, even it pubic forest glossed over as in a plaster mask.

There in that revelation was born the impulse for The Dinner Party, a collective work by 400 women into the roles and influence of women since the time of the Pharaohs that took five years to complete at a cost in today's money of $1.7 million.

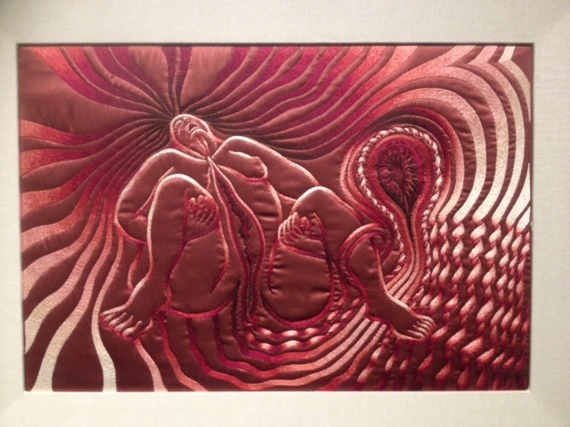

Following the dinner party came The Birth Project, involving 150 needle workers, plasticians and designers from three countries generating 100 separate panels aimed at reinterpreting the Genesis version Adam's birth from God's rib. Chicago characterized The Birth Project at the time as an exploration of the "primordial female self hidden among the recesses of my soul...the birthing woman is part of the dawn of creation." If The Birth Project drew less general notoriety and denunciation from the right wing, it also gathered a nationwide following among home health workers and natural birth advocates.

One of those health activists, Erika Kramer, who was then living in Northern California, credited Chicago's pieces as helping to open a radically new approach linking art and women's sensibilities. "When she made The Dinner Party, she brought the vagina into its flowery truth," Kramer, now a French resident, told me. "I was working in women's health and one of the first things we needed to do was introduce women to their own bodies. It was this secret part that was usually carried beneath underpants. I must have taken 15 or more photographs of the canal opened with speculums, looking into the whole tunnel with a flashlight and a mirror we would share in a small and healthy group of women in a storefront. The artists are very important in a woman knowledge of herself."

Other feminists were not so kind, as Mrs. Chicago recalled at the opening of the Bordeaux exhibit. "I've been the target of pretty harsh feminist criticism... articles that claimed I was reducing women to mere body parts. I was trying to produce images of body parts that weren't being seen." Others rejected her paintings and installations as nothing more than "cunt art," a phrase she enjoys repeating. "Cunt art?" she laughed, repeating the term before her French audience. "Cunt is the worst word you can say about some woman over there. Well what am I supposed to do? I've got one."

The men in the auditorium squirmed. The women hooted in laughter. Soon enough, Chicago returned to the core of her work as an artist, an activist and a scholar of women's history, and how all three converged in her work to address "the deficit" of women in art and the "deficit" represented by portrayals of incomplete bodies, not least the notion that the female body is "passive."

"The vulva," she began, is a very active organ. Men never saw childbirths themselves. I watched a lot of births and nothing prepared me for what I saw. Anybody who's ever seen a vulva giving birth knows that the vulva is a very strong organ. How could you say there's nothing down there?!"

The vulva and its surrounds with all its actual and metaphorical meanings had at last found its place in contemporary art and acknowledgement, due in no small part to Judy Chicago.

Forthcoming in June from Bloomsbury publishers