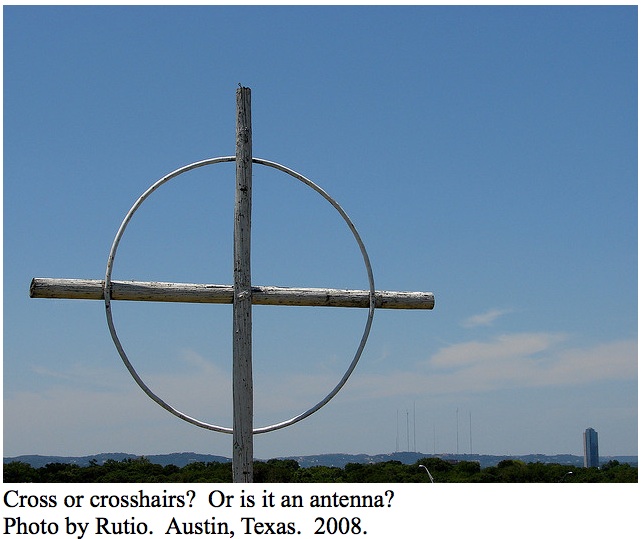

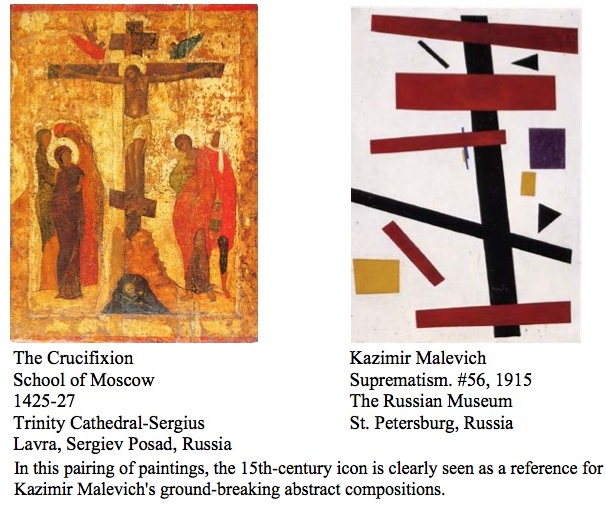

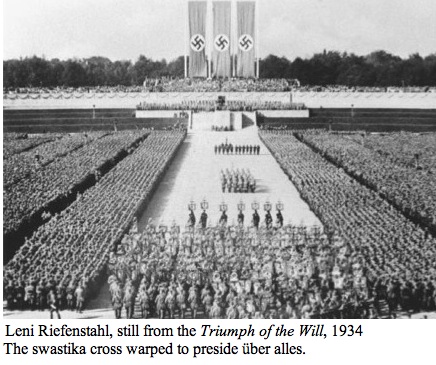

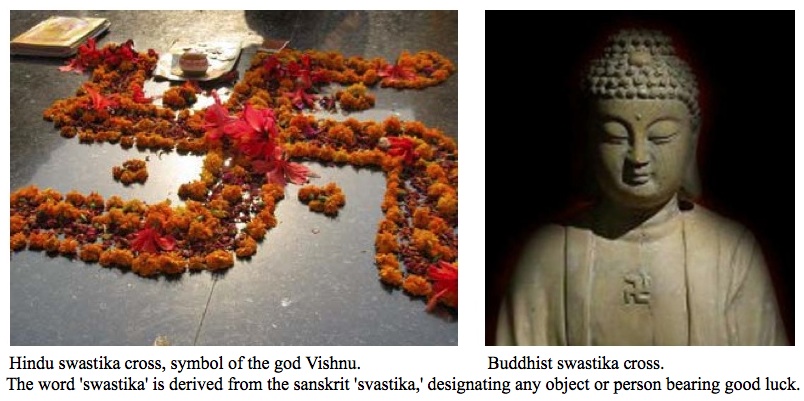

This post is made up of two separate but related narratives--one told with words and one with pictures and signs. We need words to find out how we misread signs: How Sarah Palin misread the sign of the gun crosshairs on a map targeting campaigning Democrats. How the Catholic League and the Smithsonian Institute misread David Wojnarowicz's video crucifix overrun by ants. As for the story told with pictures, it seems we might gain some perspective on both the Palin and the Wojnarowicz affairs by acquainting ourselves with the diverse ways the cross and the crosshairs have been portrayed throughout history. For the history of signage is so rife with appropriations, co-optings, and erasures of meaning, we cannot help but see that signs rarely remain in the possession of any one social milieu or culture. Signs can change their meaning and value within one generation--shifitng from benefic to malefic and back at alarming speeds. We may resist and protest the re-appropriation and redefinition of signage all we want; with the facility of signs so open to new meaning, there is little we can do to ensure the fidelity of signs to any one, universal symbolism or iconography.

It's arguable that all conflicts begin with miscommunication. In speech and writing it breaks down to a matter of semantics, but in visual communication, it's all about knowing how to read the signs, symbols, and icons with which we come in physical contact. We're all aware of the problems of illiteracy. But, sadly, few of us have ever heard of visual illiteracy, which most of us suffer acutely.

A misreading of signs is so common it's never news, though the effects of our misreadings--accidents, financial crises, even wars--fill the headlines. Which is why the news in the past few weeks of the misreadings of two of our culture's most recognizable and potently affecting signs--the Christian cross and the target sight crosshairs--unleashed deeply entrenched political tensions across America. In both cases it was a visually literate artist who imbued the signs with a sensitive political charge. And what ultimately set off the conflict over each was the cultural disconnect between the artist and public officials that stems from visual illiteracy. Unless, of course, it wasn't visual illiteracy, but callous intent that underpins each offense. But bereft of the evidence of malfeasance, why be miserly in our assumption?

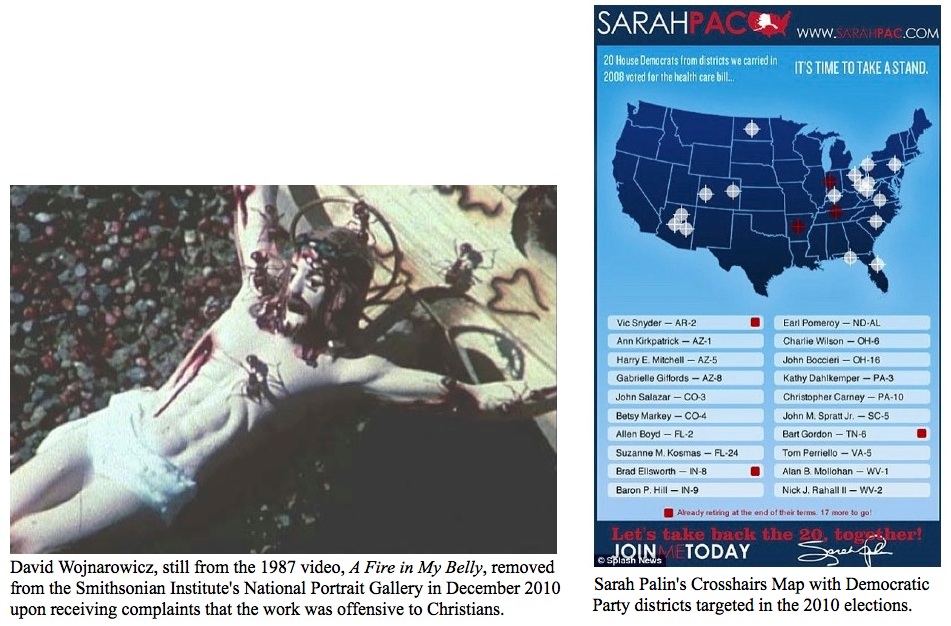

Visual illiteracy does seem to lie at the heart of the more devastating of the controversies, that over the target crosshairs, which arose in the wake of this month's assassination attempt on House Representative Gabrielle Giffords that left six people dead. With the media seizing on every alleged provocation for the killings, television news began airing a video interview with Giffords last summer, in which the Congresswoman expresses concern over a map of the continental United States commissioned by Sarah Palin as part of her campaign endorsements in the November 2010 congressional elections. Of concern are the twenty graphically seductive yet ominous target crosshairs overlain the districts of twenty Democratic congressional representatives seeking reelection.

Since Giffords' was one of the districts targeted, in the wake of her shooting pundits grappled with how responsible Palin and her team was in connoting that Democrats be singled out by Republicans and Tea Partiers to be "eliminated." In the end, few believe that Palin's crosshairs map was any more than the bravada of a tough-talking narcissist who revels in high profile partisan politics and suffers a chronic illiteracy of signs and their effect on the public. And, anyway, no one has so far been able to link Palin's crosshairs map to the gunman's deranged targeting of Gifford. Yet history tells us that within a population obsessed with media signage, there are enough armed and paranoid schizophrenics awaiting signs heralding Armageddon to make the randomly deranged catastrophe a certainty upon sight of the "right" sign.

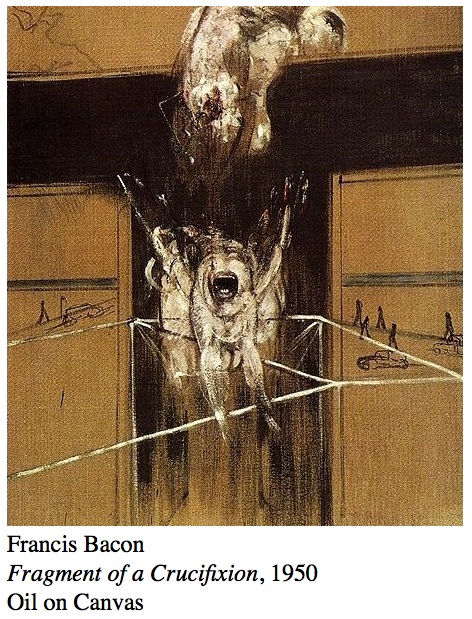

By comparison to the Tucson shootings, the controversy arising over a work of art removed from an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. has remained relatively civil. The sign of contention is a crucifix that appears in the 1987 video A Fire In My Belly, by David Wojnarowicz, a gay artist who died in 1992 of AIDS. And really it is the image of a plaster Jesus overrun by an army of large black ants that ignites the flames. Shortly after the video was included in the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery's temporary exhibit Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, the work was deemed offensive by the Catholic League, prompting incoming House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and House Republican Leader John Boehner to put pressure on the museum to remove the video from the show. Seven weeks in, the controversy has yet to be resolved as the censorship remains in effect and the protests are ongoing. But if the new Republican House of Representatives has its way, the censorship and the protests may yet prove to have consequences for other cultural institutions both in terms of withholding government funding and censorship of the art exhibited.

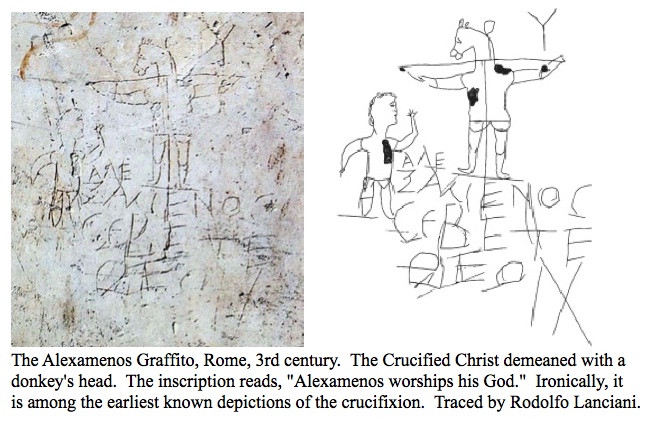

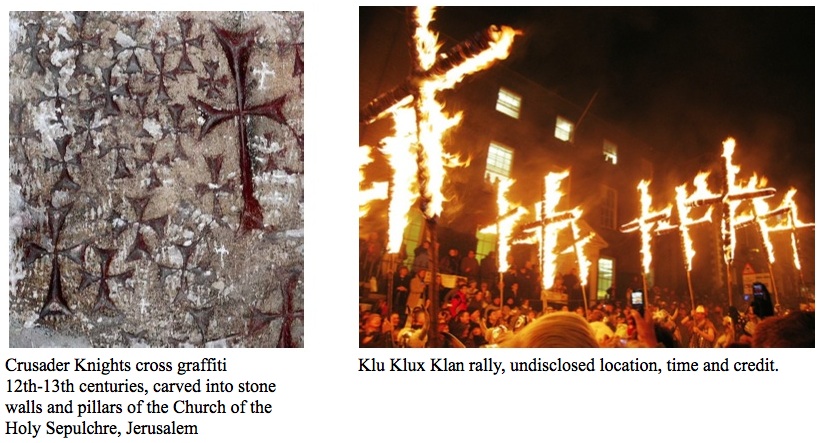

At heart, the overwrought response to the Wojnarowicz video raises the question whether it was the artist, the curators, the censors, or all concerned who took liberties with our First Amendment right to free speech and its separation from religion. And, relatedly, the fire hot issue at the heart of the Palin crosshairs map burns around the question of when artistic license seriously endangers lives. Of course the tempests over both works have arisen largely because both the cross and the crosshairs aren't just signs in the hands of artists. They are international symbols and icons with diversely interpreted meanings, most of which are highly charged with references to life and death. To a cadre of militant extremists, the crosshairs on the Palin map may read as an invitation. And no one needs reminding the Smithsonian's censorship of Wojnarowicz echos the Nazi purge of "degenerate" art; though Wojnarowicz himself must have known the kind of bloodlust that was unleashed in centuries past by the sight of the cross desecrated by the enemies of Christianity.

Even if the artists deliberately sought to unleash a political flash fire as we are led to believe from the level of sophistication in both the renderings of the crosshairs map and the crucifix video, the real problem arises in the disconnect between the artists and the public regarding their work. The artists were working on the abstract and ironic levels of signage. Whether or not it was mischief or serious dissent that motivated them, it's the public's interpretation of their art that bares the consequences. And herein lies the problem: the artists may have been working with the abstract and ironic features of signs, but the public generally receives the work on the more emotionally charged (revered or reviled) levels of symbolism and iconography.

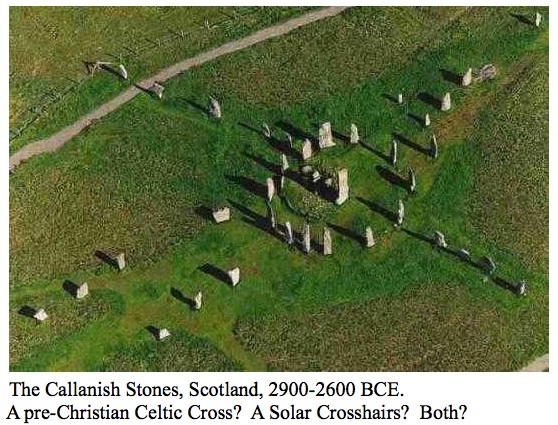

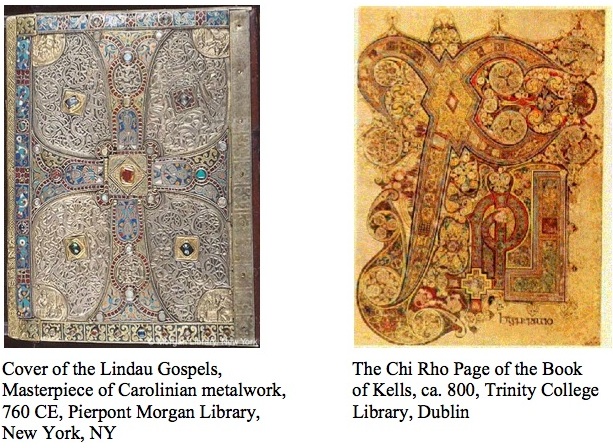

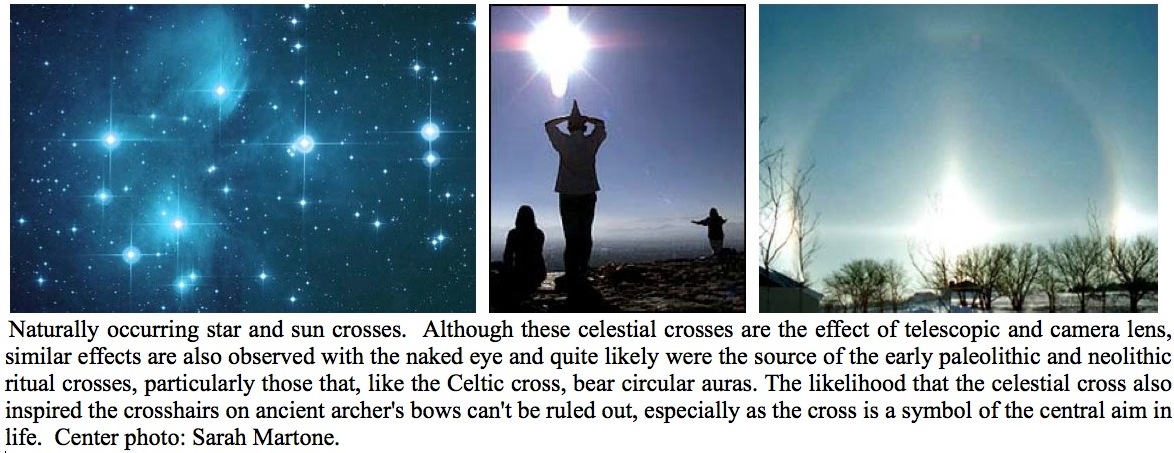

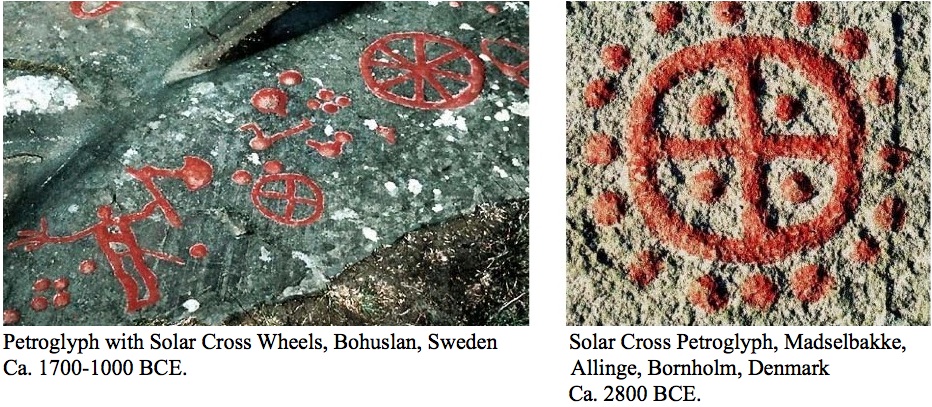

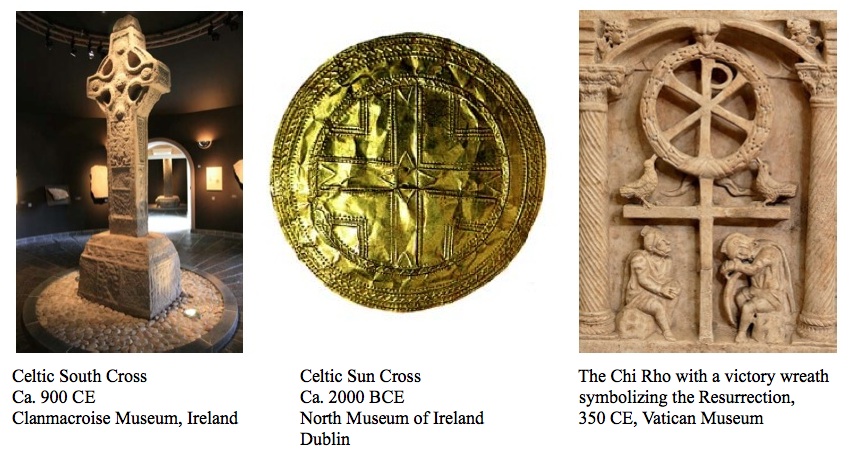

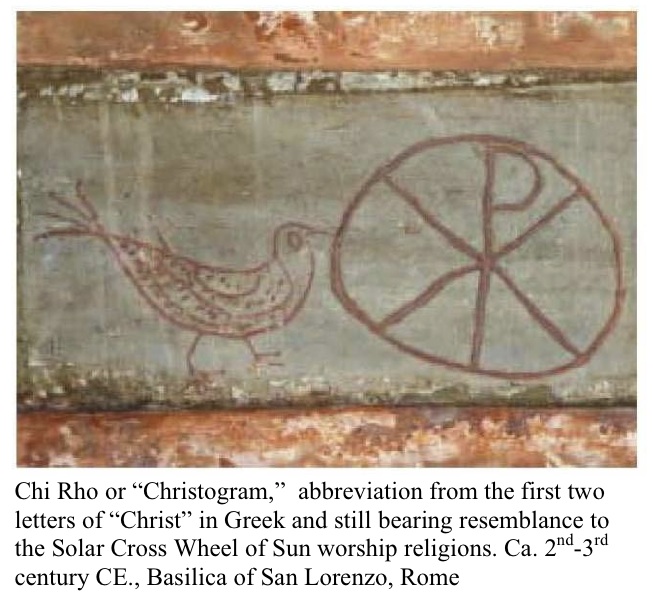

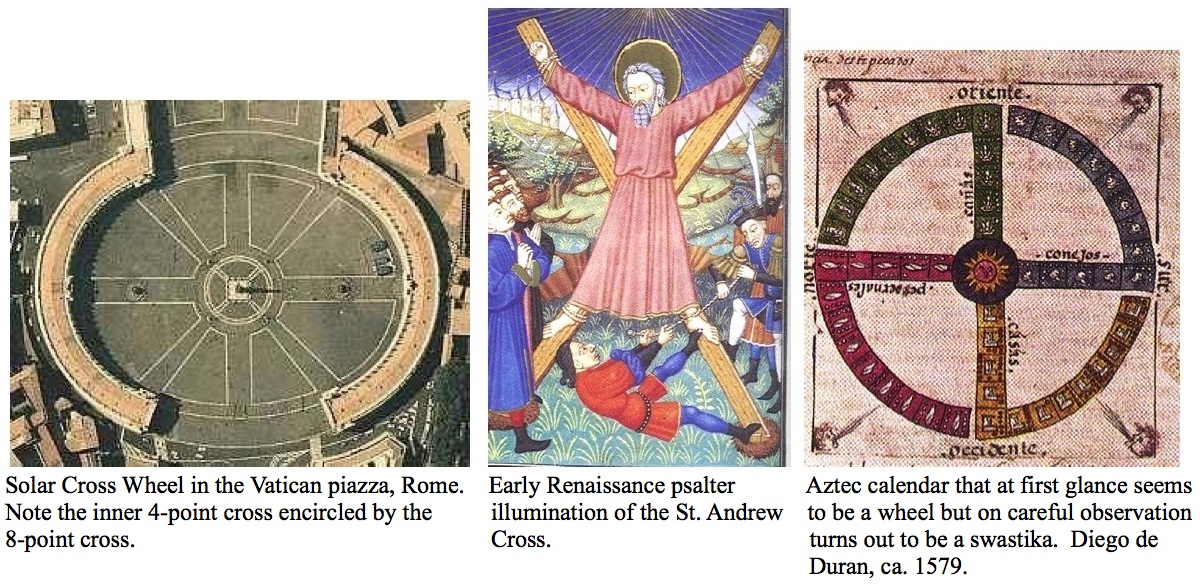

Another part of the problem arises from history. The signage of both the cross and the crosshairs can be traced back to common roots tens of thousands of years past, and at various locales around the world. In their various forms, they venerated deities before Christ and after, including the sun and the stars that, as an effect of a four-point crepuscular refraction of light, seem to form crosses and crosshairs in the sky. It's the kind of crosscultural lineage that inspires artists to scavenge from art and archeology as well as project their own meanings onto the signs, which in turn antagonizes traditionalists who see them as living symbols and icons. But the disconnect between the artists and their audiences is more than willful on the part of artists. At heart, it is the wide variance of culture and ideology that determines the multiple interpretations of signs among audiences relatively removed from the knowledge and backgrounds of artists.

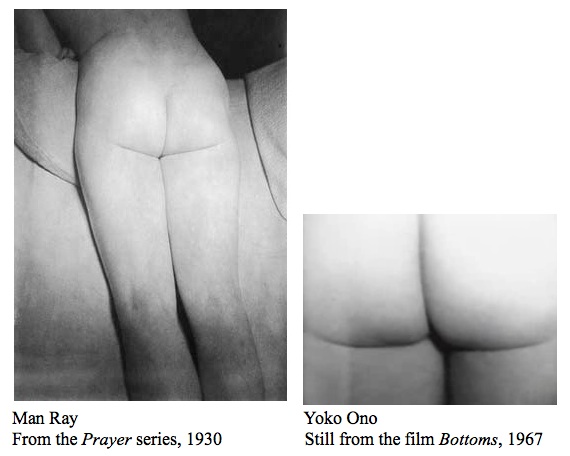

Notice the word "crotch" phonetically reflects the body's natural cruciformity.

Then, too, artists and their apologists in this age of relativism and global expansion justify the gap between artist and public on the grounds that subjectivity and cultural difference together deem it unlikely that the interpretations of signs will ever produce anything resembling consensus. But does all this necessarily mean that artists can't do more to narrow the gap between the intent of their signage and the audience's understanding of it? Do artists even want to do more, considering that ambiguity and irony are often the desired effects of art? And even if they want to, is narrowing the gap in the best interests of the rapidly growing audience for art around the world? Art is, after all, sought after because it doesn't provide the easy formulas and pat answers of entertainment.

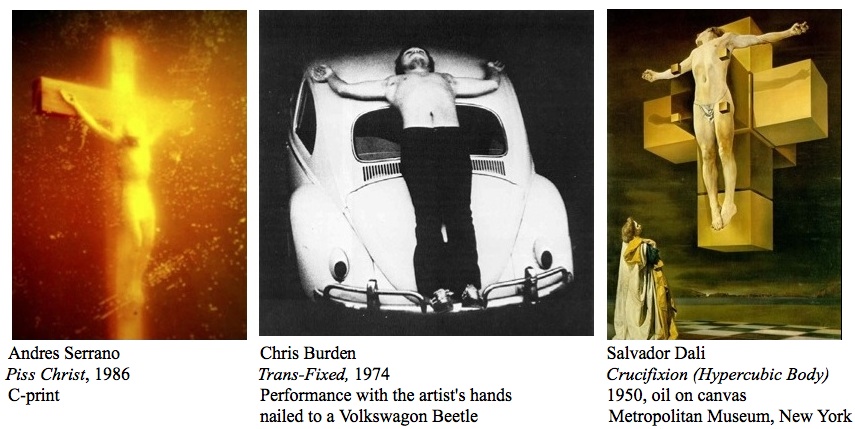

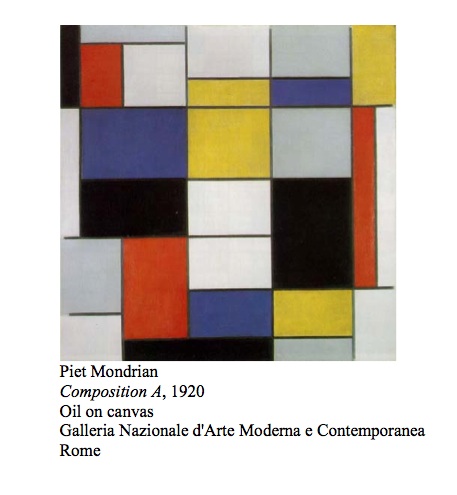

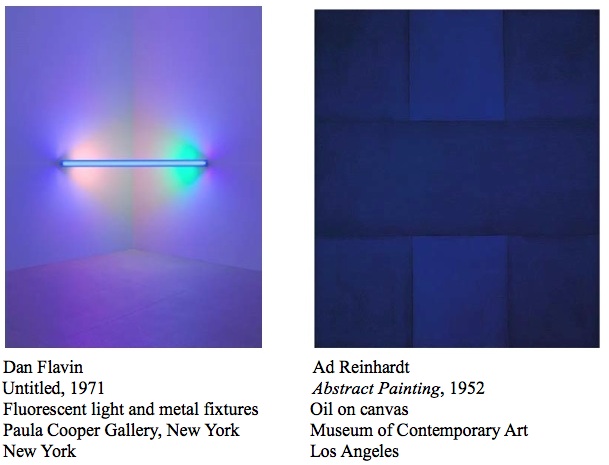

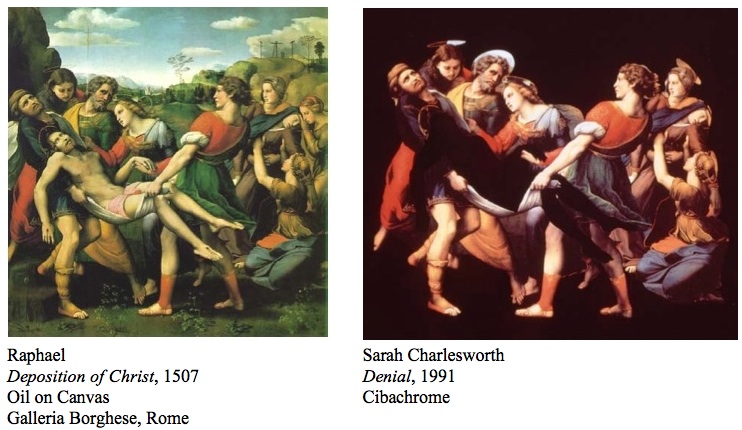

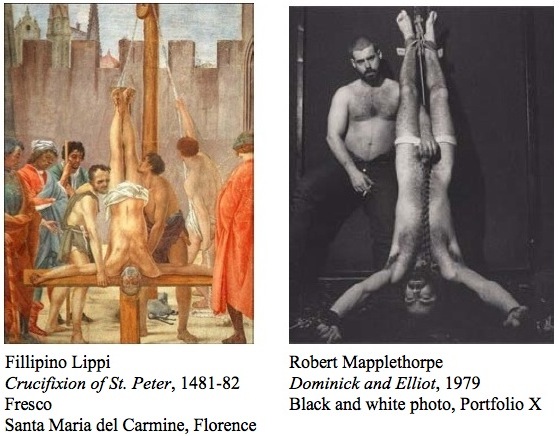

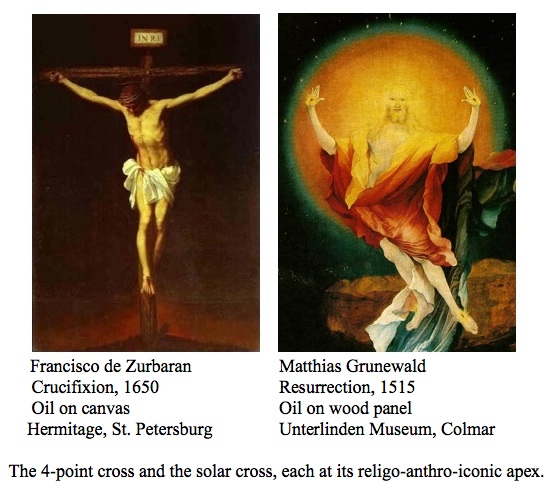

It's hard to imagine the artists depicted in the photographs of this post making the radical innovations they have if they were to concern themselves with the slippages between the intentions of their art and the interpretation of an audience. In reflecting the times and politics contemporary to their lives, significant artists by necessity remove themselves from the traditions that audiences cling to, and as such their signage is widely misread until the culture catches up with it. Yet the progression of art evolves in stages. Notice how the modernist painters in the early 20th century develop a new compositional cruciformity derived from Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox cross and crucifixion paintings of earlier centuries. We find both the earliest Christian and anti-Christian representations in the Roman catacombs and on sarcophaghi borrowing from the Classical, Neolithic, and ultimately the Paleolithic deity worship that employed cruciform signs as focal intersections signifying the converging power and continuity of life and death. Even the images associating the cross with the nude body, sexuality, and body fluids have precedents in ancient societies. The difference being that they signified the power bestowed by fertility and body cleansing that, as aspects of nature, were culturally void of the scandals that accompany the misreadings of the Wojnarowicz, Serrano, and Mapplethorpe representations of crosses seen on this post.

Freud believed that everyone is an artist when dreaming. But if that were true, we'd all be intuitively armed with an artist's knowledge of signs that might mitigate the human propensity for misreading the signs we receive from one another every day--misreadings that too often accumulate into wholesale misunderstandings with time. The most valuable knowledge we can possess is a simple understanding that we communicate with one another on three basic but ascending levels. Signs, symbols, and icons are widely thought to compose the three primary levels in the perception and reception of information. With the first level, that of the simple signification of signs, we learn as early as infancy to read signs whose meanings we begin to recognize before we can read and write. The second level builds on signs as we grow toward adolescence, but now we begin to invest in symbolic meanings that require long-term emotional investment and have long-term life consequences.

This is the realm in which ideas anchor us to individual experiences and identities. It's also the level at which the advertising moguls and political candidates can't reach us without demonstrating deep commitment to our sacred causes. Whereas signage is two-dimensional (flat), symbolism is multi-dimensional (deep). Symbolism is the meaning we bring to the center of our being and to the centers of our loved ones, and with every intention of its centering lasting for the better part of our lives. It is upon mastering symbolism that we are ready to engage the third level of visual meaning--that of iconography. This is the level on which society works collectively and historically to build cultural identities and myths. Here we commune with the legacies of ancestors while leaving behind legacies for those who follow us--all from and to people whose names we largely can't fathom but whose every lasting contribution shapes the cognition and values of those alert to them.

At the primary level of signs, we always distinguish among the world's diversity by marking out the differences we observe in the world. The sign of the cross, or the cruciform, for example, is recognized by the simple and abstract signifier of two intersecting lines or movements (three or four in Eastern Orthodox representations), which pictorially is conventionally a vertical and horizontal pairing. In the sign of the crosshairs the intersecting lines are encircled by either forming a circumference through the four outermost points equidistant from the center, or at some interval within. (See the Celtic crosses depicted). The ideas of the 'cross' and the 'crosshairs' in our minds psychologically merge with the cruciform lines and circumferences drawn on a surface, screen or sculpturally embodied. As for the signification we attach to the sign, we already know from experience that both the cross and the crosshairs are associated with choices between life and death. The result, what we call the sign of the "crosshairs," becomes associated with the balance and focus of life and death. The cruciform (the intersecting lines), by contrast, are made analogous with the concept of sacrifical death and resurrection. It is this process of conflating the form with the concept by which we disseminate all meaning. And because we disseminate all meaning with signs, including that meaning we care little or nothing about, we rarely become attached to signs alone. As such, signs alone don't generally arouse our anger or enthusiasm, since they aren't things in the world but abstractions of things. When signs are widely shared they compose language. When they are clandestine, they operate as cyphers intended to convey meaning only to initiates. In either cases, signs are the basic building blocks of more affecting visual communication.

It's only when we promote signs to the level of meaningful events in our lives that we invest signs with the charged contents that effect emotion through symbolism. We change the meaning of a sign as frequently as the culture at large requires it. But we carry the meaning of a symbol around with us, often without changing it or trading it in even over the course of a lifetime. That's because, unlike signs, symbols intensify their hold over us, becoming more psychically charged, taking on greater and greater personal significance, as time passes. The full range of this significance is not fully understood by psychologists and sociologists even after rigorous study of control groups and analysis in the field because the process of meaning investment in the symbol is largely subjective. But we do know that symbols influence, shape, even compel behavior in all aspects of life. It is symbols, not signs, that inspire our goals and become object to our obsessions. Whereas we share signs with the public without discrimination, we share symbols with only those we perceive to value what we value--people we deem to be like us. When our beloved symbols do become embroiled in a crisis imposed on by people who don't share our symbolism (think of the Star of David in the hands of Germans during the rise of the Third Reich), we often choose to endure severe tests of faith rather than surrender the symbols that are the keys to our ideology and identity

By contrast, iconography is the level of meaning that takes into account the collectivity of history and culture in full array. Icons are symbols that operate culturally, appropriating symbolism that has evolved into a widely shared or recognized history. Icons are signs and symbols that transcend the detached status of signs and the subjective and local status of symbolism by reaching for the ideal of universality. Needless to say, in a world marked chronically by difference and relativity, the icon always falls short of universality for the simple reason that universality evades the interests that cement tribes, ethnic groups, even nations. If globalism seemingly holds out the promise of universal signage, symbolism, and iconography, it's only because in its search of universality the greater diversity is radically diminished. In a world of converging signs, symbols, and iconographies, an imagined common global culture composed of a dominant and shared language can only attain universality by authorial enforcement from above, and thereby impoverishing the world by depriving it of its teeming diversity. We can only hope this imagined authoritarian achievement strikes all heads of state as untenable before they attempt implementation.

I wrote that there are three widely recognized levels of meaning. But I personally find there to be a fourth level as well, one that isn't so well understood for being largely neglected until recently by science, despite its ancient, perhaps even animal lineage. I am speaking now of the largely unconscious habit, but in singular cases wholly conscious and willful discipline, of humans living as signs, symbols, and icons. This is the level of meaning-experience integration attained only by the true believer, the patriot, the mystic, the martyr for a cause, the individual who has met the extreme test of her own beliefs. This is the level on which the individual strives to become a living embodiment and fulfillment of the icon. It is the psychological sublimation of the sign, symbol, and icon to a level of obsessive compulsion, or in romantic terms, the striving for and attainment of transcendence and completion. More mundanely, it's the response to the world that gives basis to the presumed spiritual impetus, the drive to become one with the individual's image of God, Nature, or the Whole--one reason why science has largely shunned its study. This is the level of meaning-identification (of becoming what we mean) that distinguishes the "true believer" from the greater mass of pragmatic and political humanity who see themselves as separate and distinct from signs, symbols, and icons. It is a level we have good reason to doubt and to fear, considering that in this age of the suicide bomber, the fourth level of meaning-self integration is clearly a state of being capable of fatally conflating sign, symbol, icon, and life in some tragically warped misreading of the cosmological "completion in annihilation," the kind modelled on destroyer gods (Shiva/Kali) and the death of stars. And yet meaning-self integration also stirs the heroism of the soldier, first responder, and selfless care worker who saves lives, and thereby cannot be affordably disposed of or disparaged.

In light of these different levels of meaning, it appears no small irony that the graphic signs of the cross and the crosshairs currently being debated in and around the media won't be resolved so long as the advocates on either side unwittingly pit signage against symbologies and iconographies that are by their structure and function disproportionately opposed. The Smithsonian's censorship of the Wojnarowicz crucifix video and Sarah Palin's cavalier choice of employing gun crosshairs are literally shortsighted in assigning disproportionate stature to the signs in question. By "assigning disproportionate stature to the signs" I mean that people not trained in signage, symbolism, and iconography don't see that they are pitting the detached signage of an artist against the charged values of life-sustaining symbolism and iconography. As the platitude goes, the matter of comparing signs, symbols and icons is as viable as comparing apples, oranges, and pears. All they have in common are their categories of language and fruit.

As for the charge of some pundits that the graphic artist(s) and Palin strategists behind the crosshairs map purposefully courted political controversy to focus and amplify the tenor of fear already associated with Democratic control of Congress: We would do well to remember that artists and advertisers often work with highly charged symbols and icons while treating them as if they were no more than abstract, formal components of a picture or object, the signage that can be altered and transferred at will. Artists by their craft must remove themselves to some degree from the people who invest signs with deeply personal symbolism and cultural iconography, people who would never dream of thrusting their revered symbols and icons into contexts foreign to their ideology and faith. The problem becomes one of recognizing when a sign is only a sign and when it is a more deeply significant symbol or icon.

One way to distinguish a sign from a symbol or icon is to determine if it indulges irony or ambiguity. In being deeply personal, a symbol must be genuine and committed to specific meaning and values. An icon must be able to unify a collective mindset. Neither the symbol nor the icon concern themselves with a conscious mirroring, appropriation, conflation, or inversion of the visual features of a symbol or icon, nor do they point to or critique aspects of the symbol or icon that reside outside their vaunted ideologies. Irony mimics the meaning and value of a symbol or icon to tell us something about them that can't be contained in the symbol and icon itself--perhaps because it opposes, undermines, or simply objectifies the context in which symbols and icons are presented. We recognize that Wojnarowicz appropriates the symbol and icon of the crucifix, but operates solely within the sign so that he can project it with what he perceived to be his own death sentence (and that of his lover, the artist Peter Hujar) by a society that in the 1980s was still indifferent to and fearful of anyone with HIV. The artist isn't commenting on the theology of the godhead or the salvation that the Christian public attaches to the sign of the cross, though he knew fully that his appropriation would stir controversy on these grounds. Wojnarowicz focused entirely on the sign of the martyred Christ as embodiment of selfless charity, a sign he contrasts with the reality of social disenfranchisement to which some influential Christians hypocritically condemned the AIDS patient. In this respect, Wojnarowicz is neither desecrating the religious symbolism and iconography of Christianity and its God nor its theological socialism. He is merely borrowing the central sign of Christianity to remind Christians they've veered away from their own higher ideals.

It always strikes me as oddly incongruent that it's the conservatives who so often reveal themselves to be bereft of the knowledge of ironic signs in the hands of visual artists in the manner that Palin, Cantor, Boehner, and the Smithsonian officials display. It's incongruent because, ever since Ronald Reagan was in office, Republicans displayed an acute acumen for the art of verbal disinformation. For the last thirty years, Republicans have been living vindication for Plato's banishment of the poets from the Republic, such has been their talent at euphemizing greed and usurpation as economic stimulus.

In recent decades psychologists have been made well aware that the signs of religion and country activate meaning centers in the brain that few other signs come close to stimulating. If artists at times seem to break the circuitry of our exalted belief systems--scandalize us with art we perceive as breeding heresy or treason--it's because they by habit and the nature of their intimacy with the media and structure of visual and spatial forms, are more inclined to privilege the manipulation of signs at the expense of the symbols and iconography the larger culture holds dear. Then, too, artists are frequently motivated by the political and moral aim of striving to change the social order. If they more often than not fail in their efforts to effect social change, it's because even artists don't always fully understand that, unlike the surfaces of signs, the entrenchments of symbolism and iconography can't be disinterred by art alone. Art may penetrate the levels of personal symbolism and social iconography, but only when the artist shares in them. An art of signs alone, by contrast, takes decades, even centuries, to entrench its own ideological symbols and icons.

Ironically, where the sign of the cross is concerned, we have evidence that the early Christians seemed to possess an intuitive understanding that signs have the potential to become symbolic and iconic over time. It's an understanding that may account for why, in the first four centuries of the Christian faith, the cross was rejected by Christians in favor of the symbol of the lamb, representing Christ as "shepherd to his flock," or the fish, with Christ as the "fisher of men." They did so because they wished not to promote their faith as a moribund commemoration of death and crucifixion, but as the celebration of the renewal of life in resurrection.

Such control over the selection of signs can be secured within groups sharing a common identity, ideology, and aim, but is untenable in democratic nations that afford signs the protection of free speech. Were we to begin prosecuting the promoters of provocative signage in art, entertainment and advertising for acts of manslaughter modeled after a television crime show or a film about Sadian sexual transgressions, how could we hope to persuade nations such as Iran, China, North Korea, and Algeria to free artists imprisoned for the graver offense of provoking civil and national unrest? Freedom of speech and artistic license means we have to distinguish offensive and irresponsible use of signage by artists, market strategists, and politicians distributed to the public from the direct, specific, and motivated imperilment and termination of individual lives. There is simply no way to reduce the general risk of signs to the specific atrocity inspired by signs without curtailing the right of free speech and artistic license--an act tantamount to declaring war on the U.S. Constitution.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.