This is Part 4 of the Timeline of Left Political Art, 1980-1989. See Part 1, 1900-1944, Part 2, 1945-1966, and Part 3, 1967-1979, on Huffington Post.

It may have been in the 1960s and the 1970s that the American Left enjoyed a tempestuous love affair with the mainstream media, what with its widespread support of Civil Rights, its dissent against the wars in Southeast Asia, and its vibrant counterculture. But it was in the 1980s and 1990s that the Left made deeper and more permanent changes in the fabric of society with regard to gaining substantial ground in terms of the social liberties and political balance gained legislatively, economically and institutionally in the expansion of the racial, gender and sexual emancipation movements. The Left also developed deeper and more nuanced theoretical and cultural productions both in the institutions of higher education and in the arts almost without the notice of the media. It was, after all, the period in which the West saw the Liberal policies and funding of the social and educational programs implemented in the 1960s and 1970s come to fruition in the generation that grew up watching and admiring the activists and counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. For visual artists in their twenties and thirties, this meant that the 1980s afforded them networks of publicly funded publications and alternative exhibition and screening spaces throughout North America and Western Europe for the exchange of ideas from a Left perspective. It was only natural that in such an environment that the advocates of identity politics on the Left loosely consolidated to diversify their political and economic opportunities and to ultimately expand inclusiveness in enclaves like the artworld, where they came to see their ideals reflected in the arts on a wider scale.

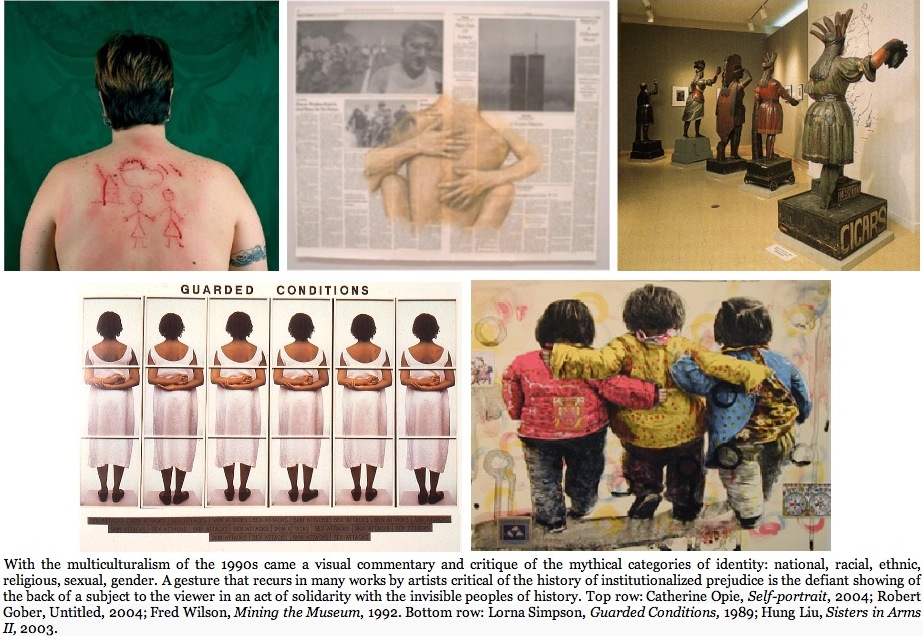

The reaction of Left artists, critics, and arts administrators in the late 1970s and early 1980s to the homogenizing tendencies that accompanied the influx of capital was to revitalize the creative underground. Following on the heels of conceptual artists in the 1970s who had taken on a starkly anti-aesthetic and ideological asceticism in their abjuration of beauty, consumerism, and popular culture--the very artists who were now their teachers in the art schools and university art departments-the 1980s generation incorporated conceptualism into even the more conventional media of painting, sculpture, picture making and narrative performance -- all of which suffered stigmatization in the 1970s. But this return of conventional media, at least among Left artists, was accomplished with a cost--the devaluation of craftsmanship and aesthetic allure that had guaranteed an object's commodification as "high art" in earlier decades. The art of the Left in the 1980s and 1990s sought surface values that registered as being visually repellent to commodification. Gritty and grimy materiality and appearance became de rigueur, as did the mass-produced and widely circulated image that established a new valuation of valor found in the copied, appropriated, dispensable and irredeemable attributes of objects and images. Artists and critics reached for theory such as that of Baudrillard which valorized the copy and the simulacrum, or that of Lacan, Derrida and Kristeva, which sought the ideological deconstruction of the signage of status quo, ethnocentrism, and false cultural certainty. Posters, wallpaper, Xeroxed signs, all of which decay rapidly, photographic images that become quickly fugitive, were the preferred media of the Left political artist, circa 1980, especially those who joined collectives that reinforced this predilection. Even the installation art that marked an artist as Postminimalist or Conceptualist was rejected if it was installed in the environs of affluence or lacked political activism. In 1980, a new generation of artists made and showed art in abandoned buildings in economically-challenged, rat-infested neighborhoods covered with graffiti, and soon incorporated graffiti itself, especially that made by the very artists who public officials sought to prosecute for public vandalism. In the end, it was all for naught, as even these so-called "anti-aesthetic" productions became subsumed into high culture, as had the found objects of the Surrealists, the throw-aways of the Dada, Fluxus and the Situationist artists before them. And so, as cycles go, what remained of the avant-garde by the 1990s felt compelled to admit that all productions, "high" and "low," were available to the new multiculturalist art breaking down barriers--and without risk of stigmatization.

In terms of the social and political contexts and contents of the Left art produced in the 1980s and 1990s, three separate directions tended to dominate artists not interested in formal concerns and wishing to radicalized their art. All three stem from a disaffection with the "ideological lockstep" of 1960s and 1970s Left radicalism and identity politics--what in the 1980s became derisively called "essentialism," after the Existentialists' critique of essence. But with the world still focused on Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand in the early 1970s, politicized psychological, sociological, cultural, and erotic theories regarding human desire entered through the back door of Left political enclaves almost without notice by those outside the Feminist and Gay Pride movements. By the late 1970s, however, with the U.S. withdrawal from Southeast Asia, and with the democratic nations of the West generally exhausted from their former and failed aspirations for empire--at least in that most all their expansionist campaigns and interventions had ended--Left and Right politics became increasingly energized by domestic disputes over the civil rights of their national citizenry and immigrants.

By 1980, the slogan "The Personal IS Political" grew into a kind of colloquial mantra on college campuses, in the liberal workplace, in the home, even on the street. At the same time, in more elite theoretical circles, Desire became not only a legitimate subject of political inquiry, it became the site of political activism. The "Personal IS Political" and "the contingency of Desire" had become so ubiquitously chimed by the New Left that it became near impossible to privilege the Old Left's high ground of collective aims (the Good and the Just) over the individual contingencies of basic personal identity and eroticism without being confronted and leveled by some advocate of individualist imperatives. Similar debates in France, and to a lesser extent in Britain, seethed until the Old Left either conceded or died away. Add to this the growing unrest of women and homosexuals spreading beyond Western borders, and especially with the HIV retrovirus rapidly spreading world-wide, even conservative and orthodox cultures became marked by pronounced Lefts and Rights to a degree not known in modern times. Age-old traditions such as hijab, women's genital mutilation, child brides, male polygamy and forced marriages that women in traditional cultures endured, suddenly divided familial, local, even national populations into progressive and conservative parties. Homosexuality and transgendering--which increasing showed itself to be ubiquitous, however deeply suppressed locally and traditionally--spurred reactionary laws, penalization and executions, which in turned spawned international amnesty movements contributing to basic civil rights agenda being made requirements of diplomatic discussion before proceeding with the dialogue between democratic and autocratic states. All of this statecraft becomes relevant to the artist who makes social and political concerns the cornerstone of their art (think of Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jaar, Jenny Holzer, Cildo Meireles, Juan Muñoz, Dennis Adams, Shirin Neshat). It became assumed that there can be no art of desire, the body, health, personal identity, economy, sexuality, gender and intimate relations of any kind, without there first being a cognizance of global affairs, just as their can be no political unity without an account of the interests of individuals. This is what it means to make the personal political.

From this vantage, a second front for art can be seen opening out onto the sites where boundaries were being dismantled. The 1980s and 1990s are the decades in which the Second World of communist-block autocracies devolved and ultimately imploded, pulling down the iron curtains, cement walls, and bronze idols of marxist-leninist communism with them. The reunification of Germany, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the entry and proliferation of capitalism in China, the coups, both violent and democratic, against dictators in Latin American, African, and Asia, the profusion of guerrilla insurgencies waged almost without regard for borders, and especially the flow of capital from the Western capitals to the former colonies in what had for decades been called the Third World, came to inform the Left political art of the 1980s and 1990s. In some quarters, both Left and Right, this global dismantling of autocracy became known as "The End of History," an ironic phraseology that signified shift in ideals, tactics, and strategies that assumed new possibilities for a human society and its environment could neither be thought of as continuations of old utopian ideals nor as existing in the same historical continuum as the newly emergent global orders. In some artistic quarters, a variant of this ideology claimed "The Death of Art."

The third front is really a reflection of the Personal IS Political and The End of History, in that the dissent that had begun in the 1950s, raged in the 1960s, and settled into long-term activist interest groups in the 1970s, by the 1980s became self-reflective, to the extent that the theoretical shifts in aesthetic, social, and political thought were seen to have broken from the earlier ideological parameters of modernism. This was a period in which the populations liberated from both traditional authoritarian governments and revolutionary autocracies looked back to past recriminations. Around the world, focus turned back to assess the effects of former colonizations and genocides. For those nations only recently liberated from despotism, the central focus was placed on finding the remains, or at least the records, of "The Disappeared," the millions of people who had vanished into jails, mass graves, and for all intents and purposes, into the thin air of Vietnam, Cambodia, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala, Uruguay, Brazil, Venezuela, the Balkans, the Soviet Union, China, Palestine, East Timor, South Africa, Uganda, Congo, and more.

All of this the art cognoscenti increasingly came to appreciate and disseminate in their art and theory to the extent that by 2000, it became near impossible not to encounter some political concern expressed by a plurality of artists in a single day's outing at the galleries and museums. Even the highest-end auction houses opened their purviews onto a perspective over-brimming with rich comparisons and contrasts found in urban neighborhoods and remote desert, rain forest, or oceanic villages alike. It was a diversity that some ideologically informed critics had decried as empty pluralism at the beginning of the 1980s, but it was a diversity that remained unrelenting and some two decades later proved itself to be the factor enabling artists at the beginning of the new millennium to identify and distinguish between open and emancipating models of art and indoctrinating rhetoric that stifles the free exchange of ideas. Exposure to this vast array of dialogue and debate better enables us as producers and consumers of art to cut across the lines of identity and ideology informing theory and art. Diversity in ideals, identity, and culture keeps us from being seduced into settling with, and becoming unknowingly conditioned by, any one system or authority before we've had the opportunity to peruse and experience the myriad models available in a pluralistic world.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, some individuals, collectives and institutions kept a constant eye on the differences between "the haves" and the "have nots" of society. Among artists, in terms of employing conceptual art practices as public dissent, the artists Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jarr, and Jenny Holzer are unsurpassed for their pointed, if often ironic, indictments of corporate and government violation of human rights. Throughout the 1980s and the 1990s, their art towers over elite and populist political artistic production alike, while shining as a paradigm of ethical inquisition into the abuse of power and wealth. In a comprehensive timeline of political art, their most public contributions alone would highlight every year with exposés as thoroughly investigated as any New York Times or Washington Post report while delivering them with a bite every bit as pungent as an expert editorial.

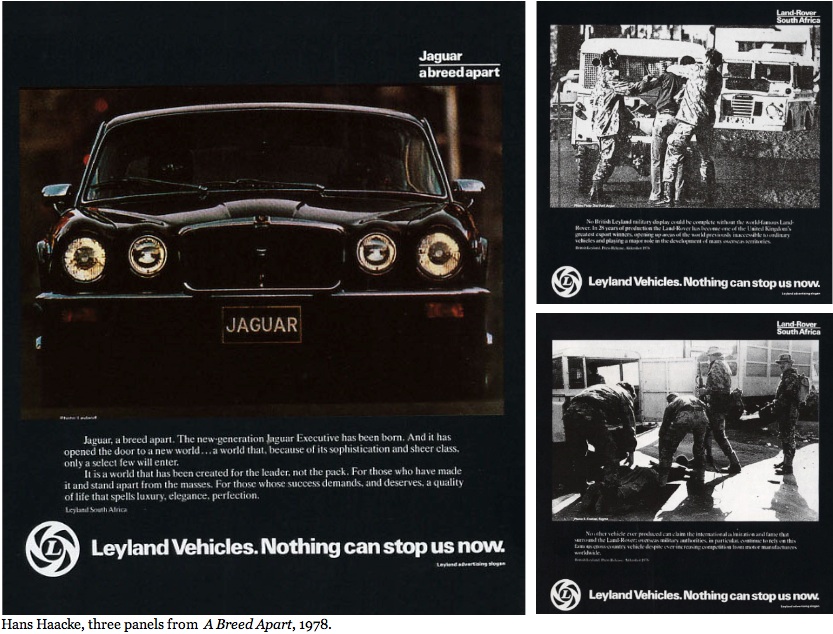

In A Breed Apart, for instance, Haacke simulates magazine ads for Leyland Vehicles, the company that supplied the white apartheid government of South Africa with the vehicles used by military officers for round ups of dissidents and other "undesirables." Haacke appropriates the actual advertising imagery and copywriting used by Leyland to appeal to the narcissism of the most affluent consumers to potentially direct us all to see that the funding for the arts that comes from such a company comes to us with an oblique history of malfeasance. Haacke doesn't beat us over the head with his findings. Many of us would simply walk away and close the discussion if he did. Which is why the artist discretely and ironically supplies us ad copy that the Leyland enterprise has intended for a specific audience. Which audience? "The new-generation Jaguar Executive ... has opened the door to a new world ... a world that, because of its sophistication and sheer class, only a select few will enter. It is a world that has been created for the leader, not the pack. For those who made it and stand apart from the masses."

Set alongside journalistic images of Leyland vehicles being used in the South African round ups of black dissidents, many who ended up disappearing and dead, Haacke's recontextualization of the company's hubris and valuation of wealth and power at the expense of humanity sound out a fascistic manifesto for a company admitting to be rewarding a populace that sees itself as a master race. But there is a more pertinent message to artists, one intimate with the highest reaches of the artworld. One of the advertising companies that promoted the South African Government's National Party in the 1970s and 1980s is the South African subsidiary of Saatchi and Saatchi, Britain's most salient and brash patrons to the arts, whose purchases have cemented many an artist's and curator's careers for life. Haacke is, after all, mindful most of all about the capacity of art to seriously critique its own assumptions.

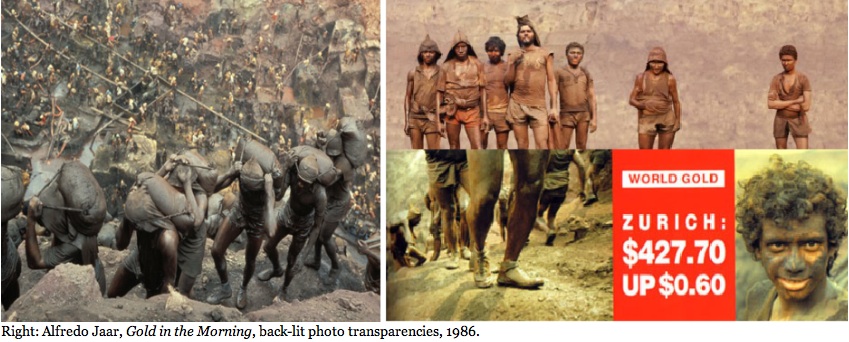

Alfredo Jaar has taken a similar route to the viewer. He is on record stating he believes that people can no longer be moved to feel or think by journalistic images, which is why Jaar often combines images with words, or familiar signs, that more gradually reveal the hidden connections between high fiance and the exploitation and abuses of laborers and ordinary citizens of poor nations. In Gold in the Morning, Jaar recontextualizes the market index for gold by pairing them with images of the laborers who endure the impoverishing wages and oppressive working conditions of the Amazon gold mines.

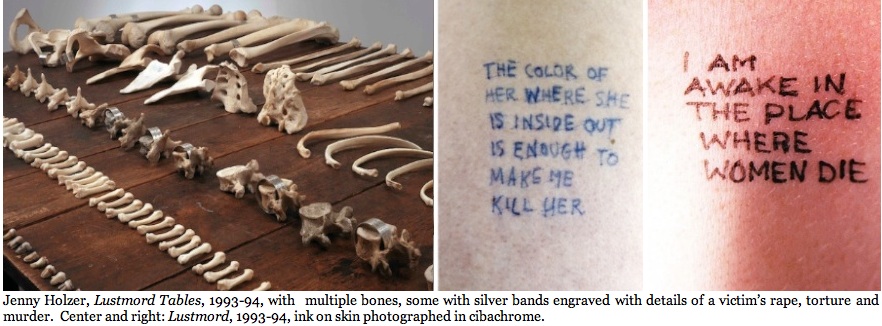

Jenny Holzer's response to the violence reported against women committed in the Bosnian ethnic cleansing of the 1990s was to begin her powerfully moving, yet critically contained, Lustmord series, named from a German word meaning murder as a sexual proclivity. The culminating exhibition of the series is not without its grisly and shattering aspects, in being comprised of two table tops overlain with bones assorted by classification, some with silver bands engraved with details of women's rape, torture and murder. On the walls hang a series of photographs taken of text written on human skin with ink containing women's blood. The texts convey three chilling perspectives on the Bosnian rapes and murders: those of the survivor, of the observer, and of the rapist. Unlike Holzer's truisms, there is no space for the mind to wander or escape, and it becomes near impossible for the feeling individual not to empathize with the deceased and surviving women invoked.

Together, the three artists and their work bracket the era of the Reagan and Bush administrations, while relentlessly countering the growing apathy and naivete of an American public being sedated and fed a steady diet of the addictive signage of great wealth and status that ladened such zeitgeist entertainment productions of the 1980s as ,Dynasty and Dallas. But then all three artists are likely aware that such a scenario had been predicted by Guy Debord thirty years earlier when he wrote at the beginning of the television age that the abundance of televised imbecilities would stifle the American working class from cultivating a political consciousness. (See the Political Art Timeline, 1945-1966.)

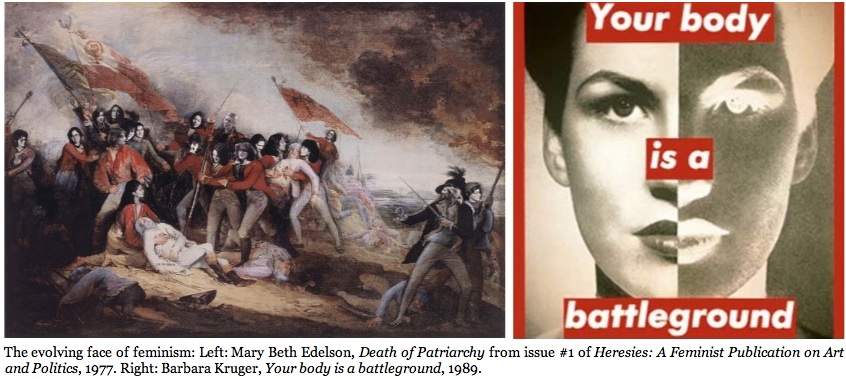

Since both the imposition of The Personal IS Political on local activism and the infiltration of political paradigms by the construct of individual desire can be attributed to the efforts of feminists, feminism has to be considered as providing the warp and the weave of the new left social fabric from 1980 onward. A comprehensive Left Political Art timeline cannot represent feminist art without showing feminism framing and structuring each and every other political effort.

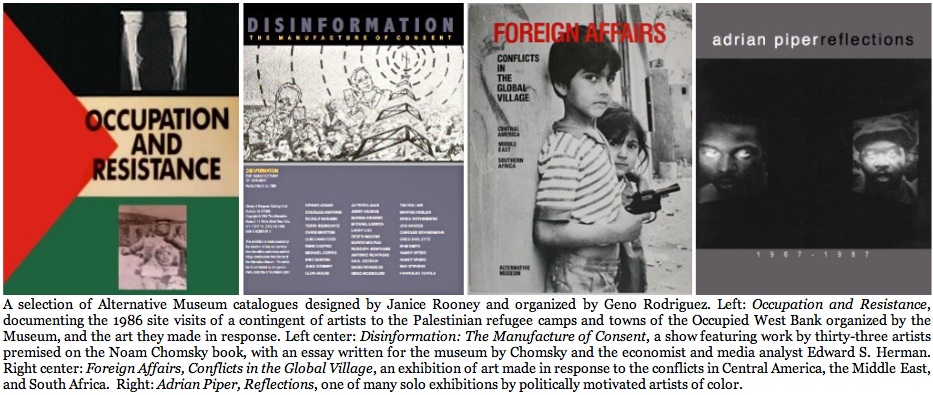

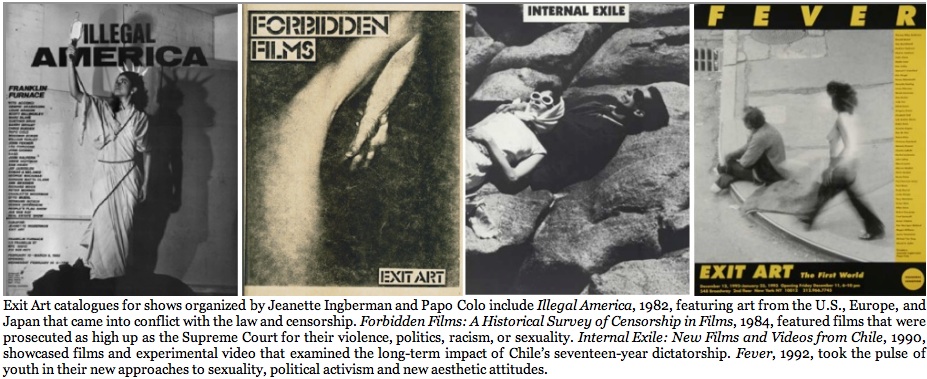

At the same time, the most politically vital art of the New Left grew out of the Alternative Space, whose golden age was the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s. Nurtured by a huge increase in art school graduates in the late 1960s and by grants from the newly established National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). In North America, the most aclaimed spaces opening their doors by year were: 1970: 112 Greene Street, later renamed White Columns, New York. 1971: The Kitchen, New York; A Space, Toronto, Canada. 1972: The Clocktower; Artists Space; A.I.R. Gallery, all New York. 1973: Artemisia Gallery and N.A.M.E. Gallery, Chicago. 1974: Hallwalls, Buffalo, New York. 1975: The Alternative Museum, New York; Real Art Ways, Hartford, Connecticut. 1976: Franklin Furnace, New York. 1977: Colab and the New Museum, New York. 1978: Fashion Moda, New York. 1979: Randolf Street Gallery, Chicago. 1980: Group Material, New York. 1982: Exit Art.

Only a few of these spaces, such as the Alternative Museum and Exit Art, made a full spectrum of Left politics their central focus, though Franklin Furnace, under Martha Wilson's direction, supplied a constant stream of politically subversive performance art. And the New Museum, under Marcia Tucker, staged several ground-breaking political shows that in many ways outflank their a-political exhibitions, in addition to issuing the book, Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, which introduced classic essays by such Cultural Studies giants as Cornel West, bell hooks, Kobena Mercer, Stuart Hall, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Monique Wittig, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak that made a deep impact on an entire generation of artists and reshaped the art context that came to be known as multiculturalism in the 1990s.

TIMELINE OF LEFTIST SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ART, PART 4: 1980-2000.

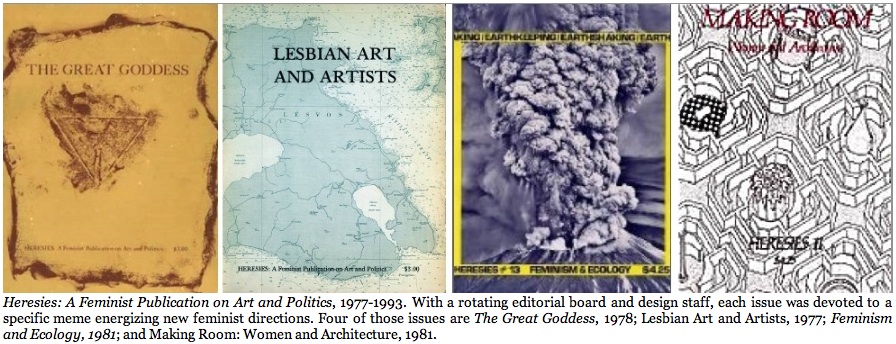

1977-1993: Of the feminist art collectives of the 1980s, perhaps the one that had the most far reaching impact is that which produced the radical art journal Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. It may have been Heresies that made the greatest impact on younger women artists throughout the 1980s--the women who would by the 1990s redefine feminism. This is in large part because the original Heresies Collective included women who would go on to make some of the most significant political art of the next three decades, along with writers, critics and historians such as Elizabeth Hess, Arlene Ladden, Lucy Lippard, and Linda Nochlin. The Heresies Collective rotated the thematic selection, compilation and editing of issues. As a result, each issue of Heresies took on a unique visual presentation and ideological tenor. Perhaps the issue having the most memorable and far reaching impact was that devoted to The Great Goddess in 1978, at that time an exciting and assertive hypothesis based on the archeological mining of prehistoric and preclassical art as evidence for widespread matriarchal societies and goddess worship thought to have been extent not only before patriarchy, but the discovery of human paternity, making the feminine principle the sole creatrix. It was a hypothesis to be shot down by archeologists and mythographers the world over, though if it survives in less enthusiastic forms today it is because the Great Goddess hypothesis has never been disproven.

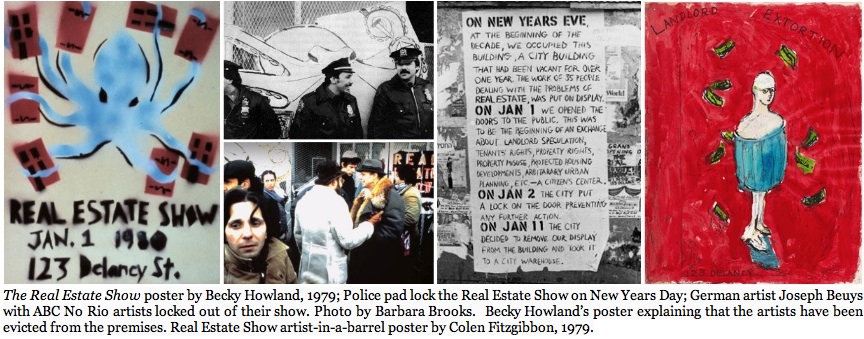

1980: The Real Estate Show, the Original NYC Art Occupation began on Dec. 30, 1979, as an activism in which 35 artists endeavored to occupy an abandoned city-owned storefront building on New York City's Lower Eastside to install its Real Estate Show without permission. "Sure, we broke in," said Alan Moore, a video artist, writer, and member of the show's organizing committee. "But we wrote letters for six months first and didn't get any answers. Artists are getting pushed around by loft landlords, by banks, by the city." Staged as a protest to the killing by police and marshals of Elizabeth Mangum, an African-American woman who resisted eviction in Flatbush in 1979, the show opened on New Years Eve. It was only on New Years Day that the artists returned to find that the space was padlocked by the NYPD at the order of the city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The incentives for the "tactical operations" of The Real Estate Show as listed by the ABC No Rio Manifesto was to "INVADE, RESTRUCTURE, AND ADMIRE; RESPECT FOR THE PEOPLE AND THEIR PLACE; "RESPECT" THE WINTER PALACE. This is a short-term occupation of vacant city-managed property. The action is extralegal -- it illuminates no legal issues, calls for no "rights."

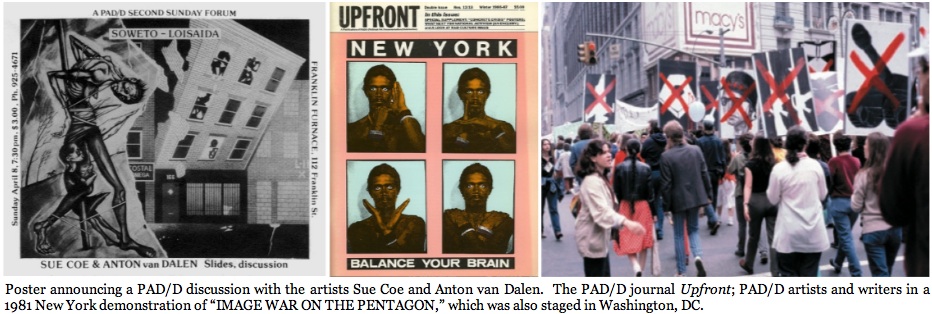

1980: After New York art critic and political activist Lucy Lippard issued a call for socially concerned artists to participate in political art events, in February a group of artists and writers organize what becomes known as Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D). In December, PAD/D issues its first statement of intent.

"Our goal is to provide artists with an organized relationship to society, to demonstrate the political effectiveness of image making. One way we are trying to do this is by building a collection of documentation of international socially concerned art. The PAD/D Archive defines social concern in the broadest sense: any work that deals with issues ranging from sexism and racism to ecological damage and other forms of human oppression." PAD/D also involved itself with the production, distribution and impact of progressive art in the culture at large, sponsoring public events, actions, and exhibitions broaching a broad range of political struggles. This includes, on May 3rd of 1981, the staging of the "IMAGE WAR ON THE PENTAGON," which consisted of PAD/D members carrying dozens of placards made by the artists (see above) during a demonstration in Washington DC on May 3rd of 1981, along with another demonstration in New York. The Image War was designed for use in the massive march on the pentagon organized by the Peopleʼs Antiwar Mobilization that drew over 100,000 people to protest budget cuts and US involvement in El Salvador and Nicaragua. It was only the first of many political actions waged by the group.

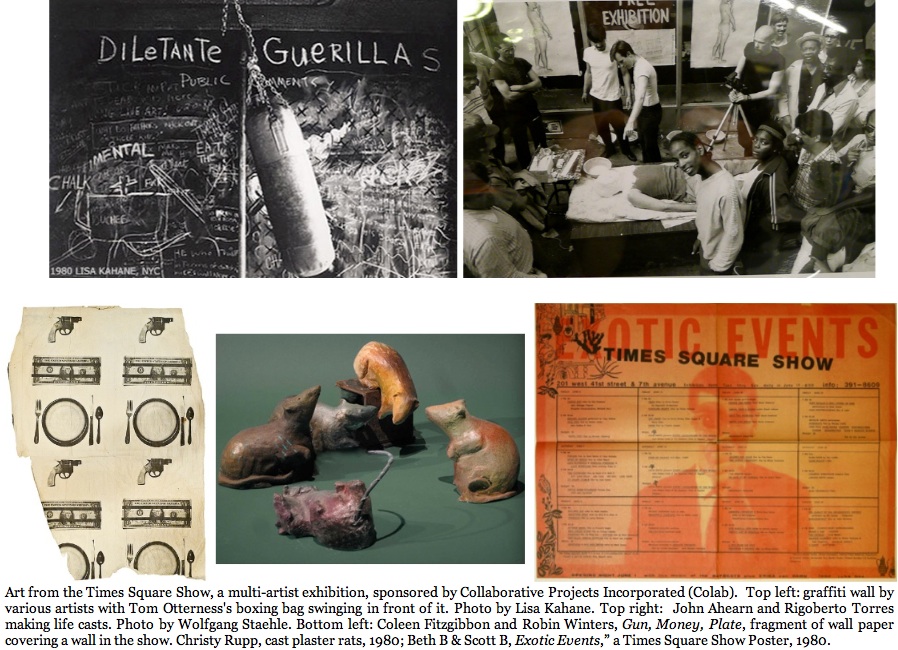

1980: The legendary Times Square Show was held at an empty massage parlor near Times Square in the Summer of 1980. More than a hundred artists installed or performed their work, using such inexpensive and often disposable media as graffiti, Xerox, and the more conventional media of painting, sculpture and photography, though with entirely unconventional applications and styles. Themes and designs were, as expected, acclimated to the then-seamy entertainment and pornography district the artists sought out and entered.

The show was a collaborative effort between Colab, a collective of artists on New York's Lower Eastside that banded together in 1977 as a union of artists to raise funds, organize exhibitions, and share equipment; Fashion Moda, a South Bronx gallery; and ABC No Rio, another artist collective from the Lower East Side (see The Real Estate Show, above). While Colab was a unique union at the time, its formation paralleled the alternative spaces organized in the 1970s, but with a more fluid, spontaneous and anarcho-democratic organization. In the beginning, a group of about forty artists met each month at different members' lofts. A much quoted Walter Robinson, who was a Colab artist-organizer (and later was to become the founder and editor of Artnet.com), has it that "Colab democracy worked because nobody could stand being in charge for very long." Colab film screenings were frequently scheduled in the East Village, and the group produced a cable television news program, All Color News, and published X Motion Picture Magazine, a collaboratively edited journal of film, photography, art and poetical reportage.

By New York Gallery standards, The Times Square Show was a purposive shambles, but one that throbbed with vibrant, offbeat life and a cultivated decadence that fit the 1980s Time Square surroundings (and the ideological ideals of the artists) as surely as the scent of urine on a hot summer night. The Village Voice called it "the first avant-garde art show of the 1980s."

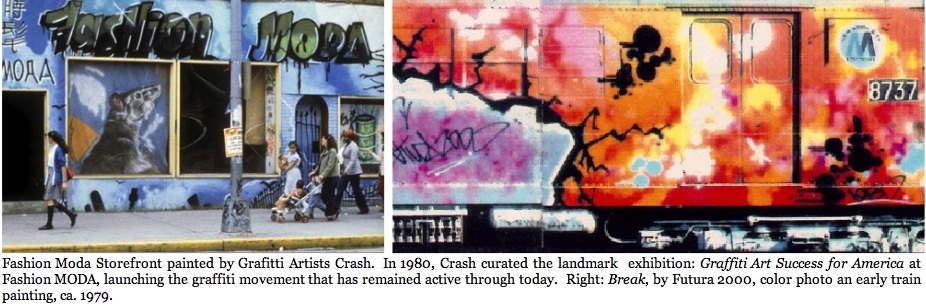

1980: Fashion Moda was from 1978 to 1993 situated in a South Bronx storefront painted by the graffiti artist Crash (John Matos), Described as combining the aspects of a community arts centre with an international, progressive arts organization, Fashion Moda was founded by artist Stefan Eins, and in a short time became associated with scores of auratic artists such as Jenny Holzer and David Wojnarowicz. But no Fashion Moda contribution is more renown, or shook up both the artistic and political establishments of New York and subsequent cities over the years, than the gallery's introduction of Graffiti Art, the result of a professional association that occurred when a young, poor Crash came upon the still new gallery. Up to this point, Crash's only experience with art was his illegal preoccupation of spray painting murals on New York City subway cars and dilapidated buildings--the poor kid-artist's ultimate protest against poverty. Graffiti Art Success for America (or GAS for America), opened on Oct. 18, 1980. Three decades later it is credited with launching the graffiti movement that today has advocates (and opponents among civic officials) virtually the world over, to the extent that some of the artists who grew up in poverty now have their own lines of Graffiti Art clothing, luggage and other sundry products.

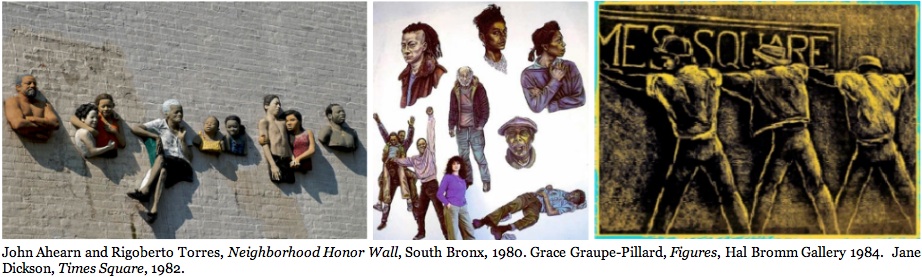

1980-1985: At the outset of the 1980s, young artists lacked the clout to diversify the New York artworld with an infusion of artists of color, but they tried to lubricate the art market for the inevitable penetration of diversity by bringing into the gallery system representations of the racial groups marginalized by the gallery system itself. If they met adversity in being neglected by the blue chip galleries, the young artists also faced the criticism of some critics and political intellectuals for veering close to exploitation by representing an experience not their own. Yet most viewers of all races enthusiastically welcomed the broadening of the contextual scope of New York art galleries, so long as it led to more opened gallery doors to artists of color. Sadly, it was a long decade before the artworld at last became infused with at least the beginnings of true multiculturalism. In the interim, John Ahearn's sculptural collaboration with Rigoberto Torres, and the paintings of Grace Graupe-Pillard and Jane Dixon, helped to revitalize the Social Realism so historically and pictorially predisposed to social and political activism by giving it both a new and timely credibility and, more importantly, by bringing to it a new audience in making portraits and compositions of an ethnic mix of people barely if ever represented in the New York Gallery scene below 125th Street.

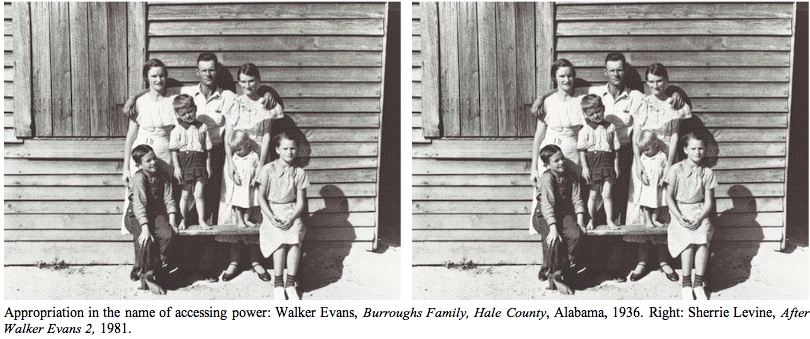

1981: The art of appropriation of other artist's work becomes most elegantly embodied and acutely politicized by the work of Sherri Levine. On one level, by making an exact copy of Walker Evan's iconic photograph (above), Levine signals that the modernist aesthetics and aura of the heroic artist-seer is a myth that has lost credence in an age of vulgar consumerism. The poor middle class of the 1930s signified by Evans dreamed of having the material comfort most middle-class consumers have today. And yet, we who are the products of an expanded middle class, in turn nostalgically look back and long for their innocence. On a more problematic level, an earnest portrayal of an impoverished sharecropper's family during the Great Depression is turned into a postmodern icon of ironic feminist appropriation. If only men can receive critical approbation, Levine points out, then a woman must "become" a man. Ironically, when Levine is astonishingly accorded access to the canon of art history and the high-financed art market she once criticized, it is because of the very audacity and eloquence of her strategy. In her case the copy does become as valuable as the original. But now that the scandal of copying another artist's work has been challenged and surmounted, the same strategy copied cannot now yield the same success for another artist. Levine's success thusly holds out no model for other women to follow. The dilemma is that of the Left artists who succeeds so well that s/he becomes part of the very institutions and markets she critiques. The question to ask now is, Since the capitalist and male-dominant artworld opened its doors wide to her, is Levine still an artist of the radical Left?

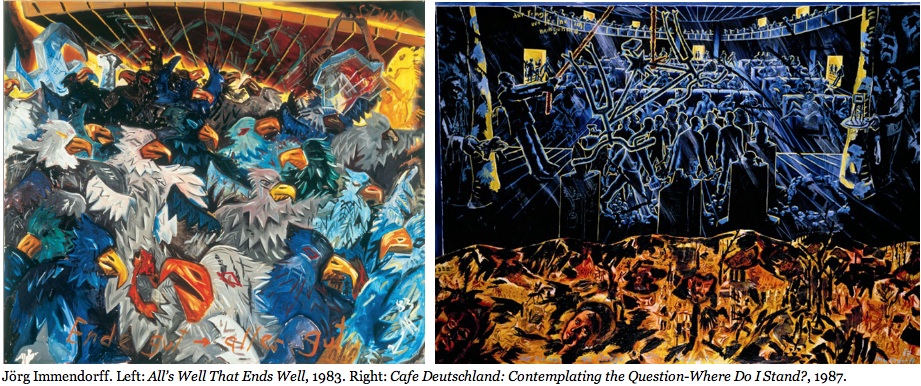

1983-87: The high artworld during the first half of the 1980s becomes dominated by a revival of Neo-expressionist painting staged largely by artists in Germany who decidedly picked up where their forebears--Emil Nolde, George Grosz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Max Beckman--had been forcibly cut off by The Third Reich. Lauded and derided alike by critics in North America and Europe, the German painters counted among the new agitated barbarians who returned to portraying figurative subjects in an often violent turbulence fraught with lurid colors and social anxiety. Among the more political Germans who sensed that the German people were nearing a breaking point both in the West, with an economic dependency on American and West European commercial and corporate culture, and in the East, with totalitarian restraints nearing the breaking point, Jörg Immendorff's fervently brooding and tumultuous canvases reflect a desperate mixture of hedonism and anarchy reaching its boiling point. Although largely mythopoetic and symbolic, the symbolism--found in such motifs as the German eagle, the Soviet sickle, and the Worker's fist--is prophetic of a politicized population turning its frustrations in on itself for want of an adversary to blame and to smash. In All's Well That Ends Well, the eagle is every German man and woman running amock for being penned in, and consequently becomes self-annihilating for want of an outlet of energies and a fulfillment of collective aspirations. In Cafe Deutschland: Contemplating the Question-Where Do I Stand?, the German people inhabit a nightclub mosh pit that churns and collides to a music that tempts with sensory stimulations but never delivers the transcendence it promises.

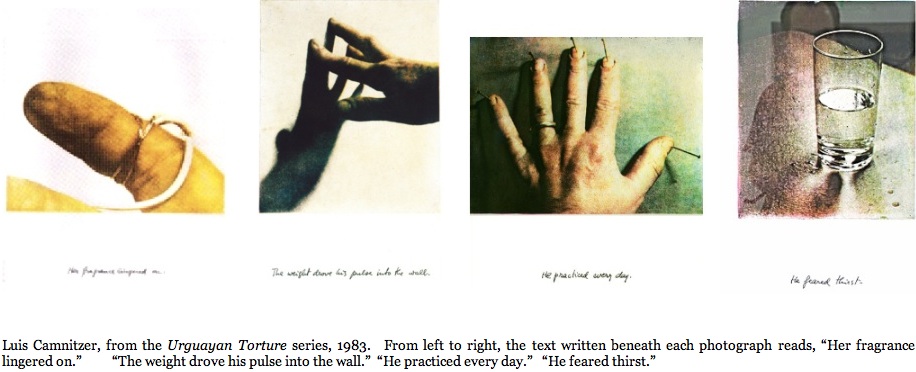

1983: The "hes" and "shes" that Luis Camnitzer poetically eulogizes in his Urguayan Torture series, are the tens of thousands of people who disappeared during the dictatorships of Latin America in the mid to latter part of the 20th century. Most were apprehended because of real or supposed opposition to the reigning governments, or because of association or mere suspicion, and were thereby thrown into jails, mass graves, and often both. Most were the victims of military juntas, reverse revolutions and coups in Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala, Uruguay, Brazil and Venezuela. Yet their disappearances still haunt the collective psyche of the afflicted nations, in part because of their sheer numbers. (Argentina's so-called Dirty War took more than an estimated 30,000 lives). The issue also resonates for some because of its visceral connection to the United States. In Chile, for instance, the U.S-supported coup against Chilean President Salvador Allende helped usher in the rule of Gen. Augusto Pinochet, under whom thousands disappeared.

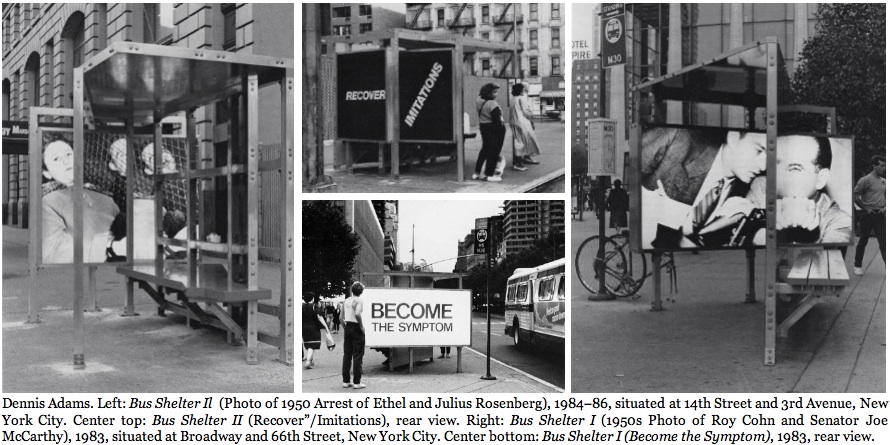

1983-84: In a series of dysfunctional and deconstructive bus shelters that Dennis Adams dispatched throughout cities in the U.S., the artist sought to intervene on the cities' mass transit systems to protect the idea of "transit" as a means of mobility and escape for those who can't afford other means of transport. Adams is particularly critical about the advertising that intrudes on commuters daily. As his bid to stave off the advertisers at certain transportation stops, the artist sought to counter the daily dosage of ads dumbing down populations. His strategy was to replace the advertising that imposes the values of profiteers into public view with ambiguously political imagery that can't be second guessed and requires the inquisitive viewer to look more deeply into the motives behind the signage they encounter daily.

But Adams' work requires an educated public to see in his historic images--those he posts in place of an ad campaign--the arrest of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg as communist spies. In fact, for his project to work, we have to already have heard that the Rosenbergs were likely scapegoats propping up a mythological red scare. Or to recognize a photo of Roy Cohn and Joe McCarthy, whose careers and public esteem profited greatly by fingering he Rosenbergs, guilty or not. But if educated people already know that the threat of communism overtaking the U.S. was a fiction, what is Adams trying to further tell us?

A clue can be found in the shelters' designs, though it is a clue that further complicates matters. "There are discrepancies in the functional conventions of the structures," Adams has stated about his shelters. "For instance, in the first bus shelter, the bench is outside the shelter area and the central wall bisects the illuminated image panel." The dysfunction of this design prompts those of us in our armchairs to think out the many questions about technology, utopianism, and the manipulative imperatives of architecture and urban planning, but they don't seem to be questions related to the images of the Rosenbergs or their interrogators. Yes, taken together the design and the imagery incline the thinking pedestrian to further consider the manifest manipulation s/he encounters from commercial interests, public institutions, and certainly architects and urban planners. But to think of these things is not likely in the haste of rush hour. Yet, in the course of many rush hours, and after the images and shelters bother us a little more each day, the accumulating irritations work us over. Adams may be overloading our capacity to read signs with contradictory readings in the short term. But in the long term--say after weeks of waiting for the bus at his shelter--our minds try to piece the puzzle together and theoretically limber up in the effort. It's this effort at problem solving that advertising, with it's imperative for the quick and easy read, refuses to supply. And in a culture whose intelligentsia increasingly discounts the notion of truth, it's the mind's exercise, its questioning, that counts.

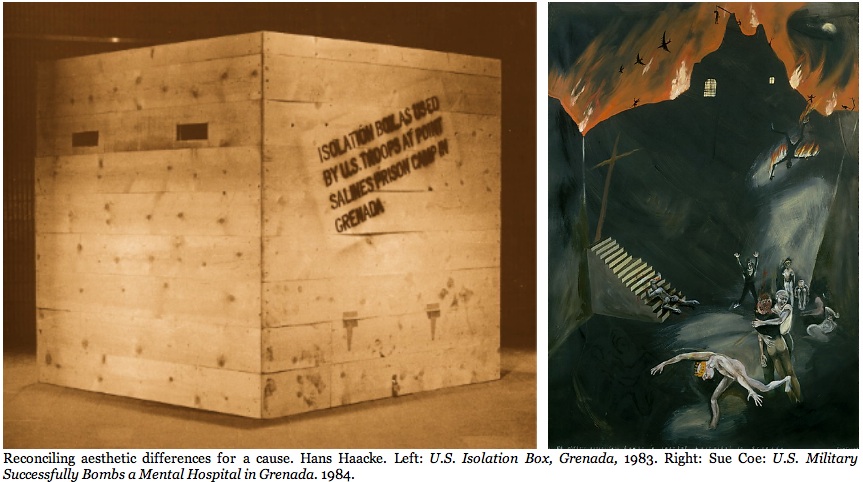

1984: The Artists' Call Against U.S. Intervention in Central America, an ad hoc coalition co-organized by Lucy Lippard, erected an exhibition at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York protesting U.S. policy in Central America. The U.S. had responded to a request from the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States to restore stability to the island nation of Grenada after a unit of the Grenadian army cooperating in a military coup led by pro-Soviet hardliners had executed Prime Minister Maurice Bishop.

Among the works installed was Hans Haacke's double-faceted sculpture, U.S. Isolation Box, Grenada, that consisted of an eight-foot, wooden-planked, unpainted cube held together with nails, in which were cut narrow window slits near the top and small ventilation holes. The box can be easily mistaken for a Donald Judd Minimalist sculpture until turning a corner and coming upon the stencil-painted words: ISOLATION BOX AS USED BY US TROOPS AT POINT SALINES PRISON CAMP IN GRENADA. I say it is double-faceted in that it offers two critiques stemming from one root. The fact that it is a replica of the actual isolation boxes built to hold detainees at Grenada's Point Salines airport by the invading U.S. troops makes it representative of the artist's indictment of the U.S. military and government for violating the Geneva Convention on Human Rights. That its entry into the context of artworld aesthetics by resemblance to the "High Art" of Minimalist sculpture underscores the neoconservative patronage of such art with which artists and curators so often interface, with or without the knowledge that the financing they court often comes with interests attached to such military invasions.

Sue Coe, another member of the coalition, protested the invasion with an expressionist painting targeting the military blunder recalled by the work's scathing title: U.S. Military Successfully Bombs a Mental Hospital in Grenada. Coe is referring to the twenty Grenadian civilians who were slain when U.S. planes mistakenly bombed the Fort Frederick mental hospital, located adjacent to the Grenadian army headquarters that was the intended target. But Coe's composition isn't as direct a narrative as it deceptively appears. The subject of a mental hospital has afforded Coe the chance to literally draw an analogy between the U.S. Presidency and Shakespeare's King Lear. A figure in the foreground of the painting, an obviously deluded patient who wears a gold crown, references Lear as he loses his sanity and wanders in a field collecting flowers while his entire Kingdom falls to the ruin of war. The key here is that Lear loses it all because he pushes the one voice of honest, critical reason away from him--his daughter Cordelia, whose truthfulness is too bitter to bear. It's a ripe correspondence of Cordelia to both Coe, Feminism and the Left, all of whose advice goes unheeded by a neoconservative U.S. administration led by actor Ronald Reagan in the role of Lear.

1984: Cildo Meireles completes Red Shift, his chamber installations begun in 1967 and alluding to his native Brazilian dictatorship. In the first room, called Impregnation, a white room is filled with hundreds of red objects, a wardrobe with red clothes and a refrigerator with red food. While viewing the contents of the room, viewers will hear a soundtrack of water dripping. At the end of Impregnation, is a darkened room called in Portuguese Entorno, meaning both "spill" and '"surrounding." A pool of red liquid apparently, yet given the great quantity of the liquid, absurdly pours from a fallen bottle. Walking deeper into the darkness, visitors find Shift, a filthy porcelain washbasin installed on a slant. A red watery liquid spills from its tap. Meireles has given indication that the installation, which evolved over eighteen years, analogizes the oppression and violence visited on Brazil by the military regime that took power in a coup in 1964, when Meireles was sixteen years old.

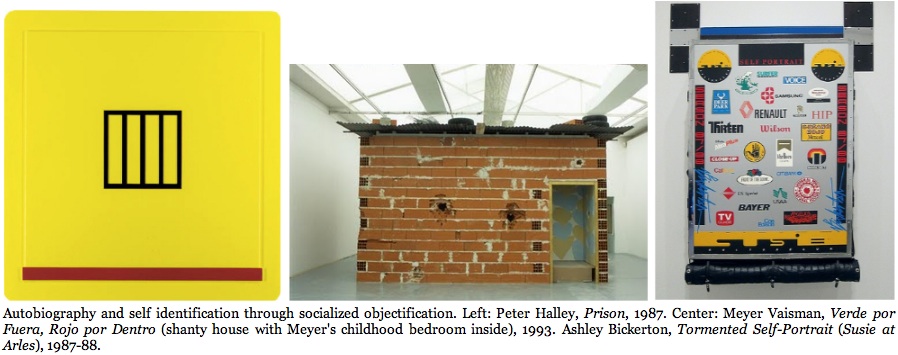

1984: Big Brother may not have materialized in 1984 as the draconian and overarching armature of despotism that George Orwell foresaw. That's not to say that the dreaded 1984 came and went without a more discrete and nuanced paternalism guiding Western society. By the mid-1980s, the Left's disaffection and subsumption by capitalism was theorized as the effect of an insidious and discretely ubiquitous commercialism permeating the veins and cells of civilization. But rather than stimulate dissent against commercial subsumption, indirect political action fell into disfavor with intellectuals and artists aligned with the new, if relatively short-lived, postmodernist vision that privileged ironic referencing over explicit social and political demonstrations. Artists now exhumed discrete social codes and reassembled them to effect discretely transgressive, if largely idiosyncratic, modes of conceptual art to reassert the primacy of personal identity. In this regard, Peter Halley routs out the formal, patterned, and architectonic restraints implicit in the social use of geometric principles and designs regulating identity. Halley's geometric paintings have been engaged in a play of relationships between personal choice and institutional regulation, with the "cell" or personal zone as the fundamental model that must conform to the increasing geometrization of social and personal space both architecturally and in the zoning of nature.

Meyer Vaisman chose to identify the physical markers of poverty--such as the rancho or shanty homes that punctuate the Venezuelan landscape and identify neighborhoods as impoverished urban populations. Vaisman would never be content with mere photographs or miniature models. He literally brings the ranchos into the gallery, as he did with the work he calls Verde por Fuera, Rojo por Dentro, to be viewed and sold to the very affluent class that allegedly perpetuates the conditions of such poverty.

Ashley Bickerton explored commercial branding as a matrix for the manufacture of middle-class consumer identity. Yet the political overtones of his work resound beyond and above the art commodity index to facilitate the viewer cognizance of his or her own consent to the expansion of commercialization. In this regard, in a work such as Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles), Bickerton's blatant appropriation of commercial and public logos affixed to a metal armature that resembles and analogizes variously a photo backdrop (the commercial landscape), an unwieldly techno-backpack (the superfluous weight of consumption we carry with us), and a vending machine made portable (for our daily fix of consumer narcosis), all to convey an illusion of esteemed social identity and status that we learn to be but the manufacture and manipulation of identity by corporations and public institutions.

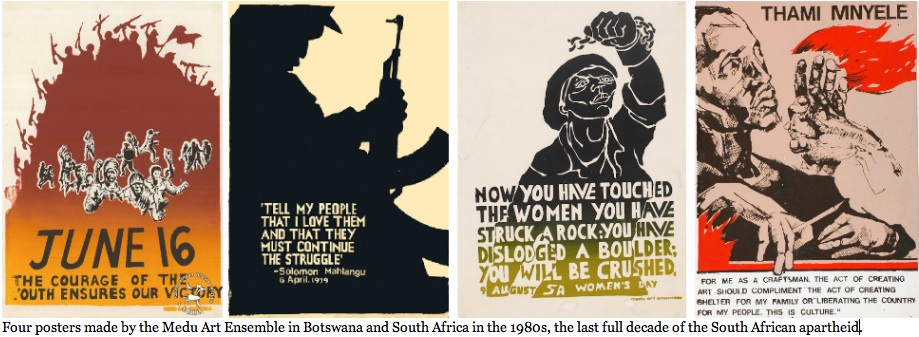

1985: South African army units went into Botswana and killed twelve artists of the Medu Art Ensemble, while destroying the homes of several others, to stop them from printing, smuggling and posting political posters in the cities and towns of South Africa. Not only did the South African government ban their work, it was illegal and severely punishable to be found with one of the Madu posters. And yet, when the Medu organized a conference to train South Africans to make their own silkscreened posters, over 5000 South Africans crossed the border into Bostwana to attend and learn. Fortunately the South African government's desperate murder and bombing of the Medu artists came too late, as South African dissidents had already set up their own domestic silkscreen workshops and studios. Despite government attempts to destroy the printing equipment, detain the artists and their employees, and bomb workshops, the posters became increasingly popular and dispersed, to the extent that they can be credited as a major impetus in the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, the lifting of the ban on anti-apartheid organizations, and the achieved independence of the black South Africans in 1994

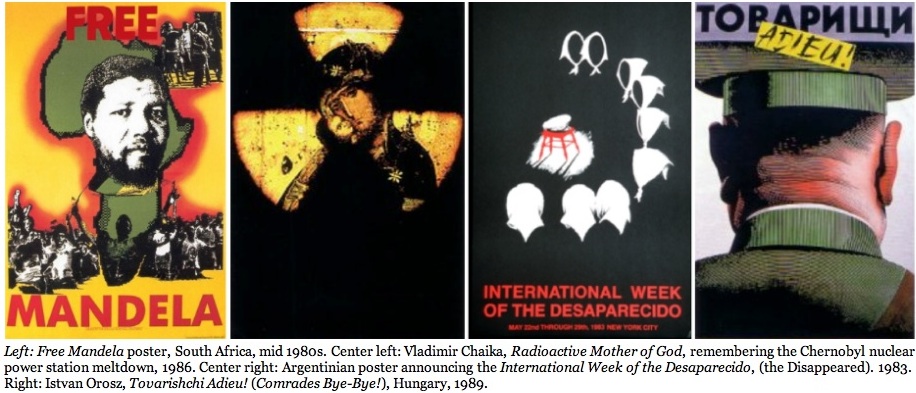

International political posters of the 1980s and 1990s. Although the popularity of the political poster in the U.S. went into decline with the Reagan-Bush era, the rest of the world, most notably those marked by either traditional authoritarian governments or revolutionary autocracies, continued to issue graphic pleas for sanity and balance in any one of the myriad hot spots on the globe.

In 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear power station meltdown in northern Ukraine embroils Europe in anti-nuclear demonstrations and debate. In 1996, when Vladimir Chaika's poster, Radioactive Mother of God, begins to be seen in Russia in time for the tenth anniversary of the 31 people killed at Chernobyl, Chaika's poster discretely indicates that little has changed under a Politburo resistant to public discussions of the facts.

The Argentinian poster announcing the International Week of the Desaparecido for 1983 depicts a circle of white head scarves symbolizing the Argentine mothers and grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo who continue to search for the whereabouts or remains of the children and grandchildren they believe were kidnapped or murdered during the Argentine military dictatorship (1976-1983). The haunting scarves face a red stool with a military hat atop it symbolizing the Argentine Military Junta.

Hungarian artist, Istvan Orosz, in his 1989 poster Tovarishchi Adieu! (Comrades Bye-Bye!), graphically articulates the joy of the Hungarians when the Soviet Union withdrew its army from Soviet-occupied Hungary.

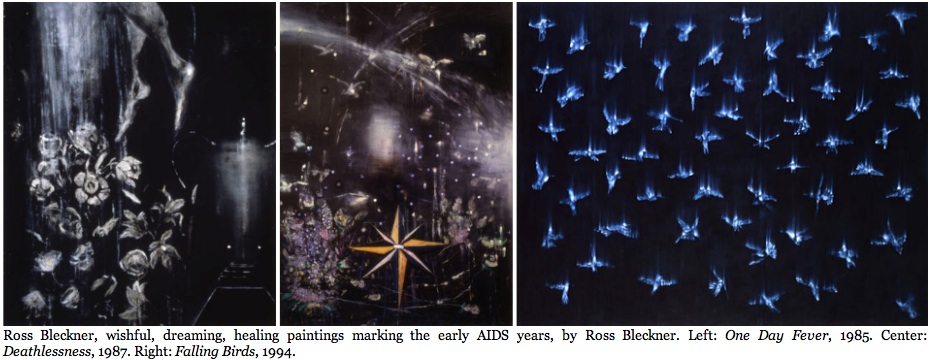

1985: Ross Bleckner proved that political art neither has to directly and pointedly articulate its subjects and objectives, nor render them in a pictorial social realism. The time and place of his exhibitions spoke for themselves. Viewers even today can see the romanticized imagery stand as painted eulogies to lost friends, even as they evoked the collective loss of a generation of survivors asking the hows, whys and what ifs of the AIDS epidemic. Which is why walking into a Bleckner exhibition in the late 1980s, though by no means a pious affair, compelled the visitor to silence and personal commemoration on no other cue but the paintings before us.

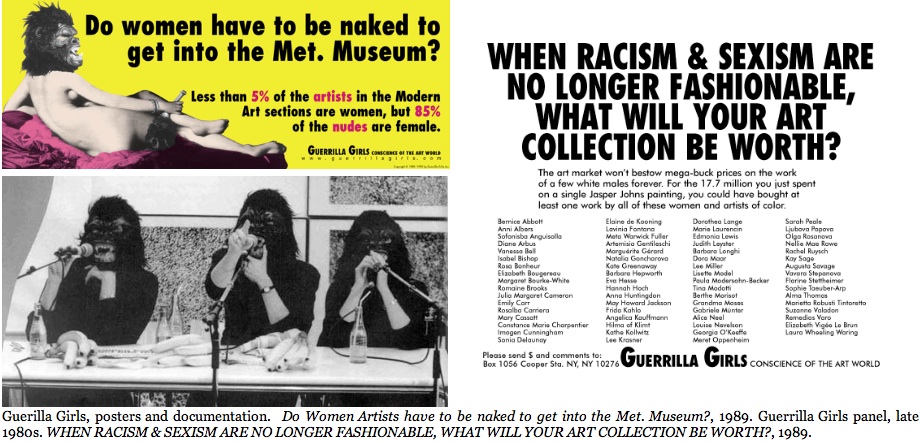

1985: When the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its exhibition, "An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture," a public outcry was raised when it became apparent that out of the 169 artists, only 17 are women, that all the artists are white and either from Europe or the US. The show's curator, Kynaston McShine, further kindles the fire when he flippantly remarks that any artist who isn't in the show should rethink "his" career." In protest a group of women artists convened wearing gorilla masks and calling themselves the Guerrilla Girls. The group will go on to issue reviews of the representation of women artists and artists of color at museums and galleries around the U.S., and later Europe, and of the artists covered by the art trade journals. Throughout their activism, the Guerrilla Girls postered the streets with scathing, but no less politically-pertinent, statistics on the ratio of white men to women and all other ethnic groups represented in the so-called canon of art history and contemporary art.

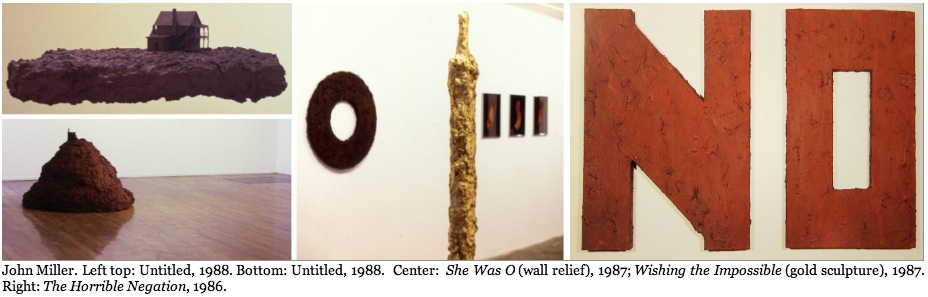

1986-1988: John Miller's fecal brown- and gold-painted sculptures and wall reliefs together embody Herbert Marcuse's notion that acting out our erotic drives, rather than the sublimation of those drives--what is really their repression and conversion into socially-approved and regulated industries and moralities--guarantees the emancipation of a civilization. In covering models of property (land, houses), or alternately symbols and signs of the social codes that repress our erotic drives, in fecal brown, Miller refers to Freud's belief that the so-called reality principle (or moral/social principle) checks the pleasure principle as early as the parent's intervention on their newborn infant's scatological pleasure is found in defecation and urination. By showing disapproval or disgust at the infant's waste, parents relay to the infant that its pleasure is shameful. As time goes on, the child's creativity efforts are channeled by authority into productive industry--what culminates into the gold standard. Miller, on Marcuse's cue, reverses that process in a radical desublimation, whereby the value of gold is reverted back into the fecal pleasure of the infant as an embodiment of the artist's emancipation of the enforced moral repression.

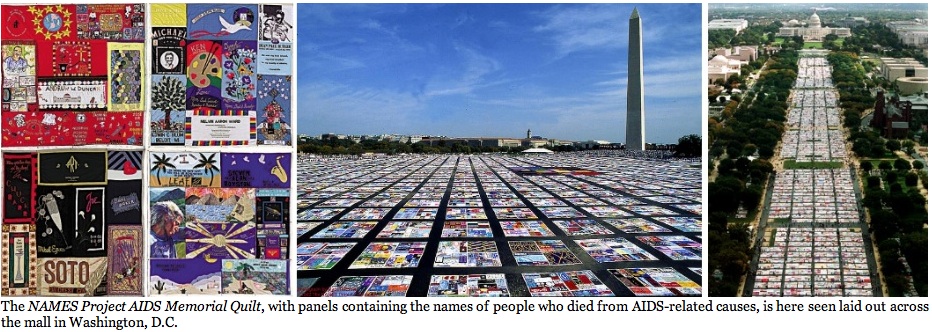

1987: The first public showing of the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt, often called the AIDS Memorial Quilt, occurs in 1987, two years after it was conceived and organized by AIDS activist Cleve Jones. The quilt was literally unrolled across the lawn of the National Mall in Washington, DC, whereby It rapidly became known as a memorial to, and celebration of, the lives of all the people who have died of AIDS-related causes. Weighing an estimated 54 tons, as of 2010, it is the largest piece of community folk art in the world. As social historian Gary Laderman notes, the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt filled a void in the lives of survivors at a time funeral homes and cemeteries refused to handle the AIDS-deceased's remains due to both the social stigma of AIDS and fear of its spread during a period before the disease came to be medically understood. During this period, the Quilt was often the only opportunity survivors had to remember and celebrate their loved ones' lives.

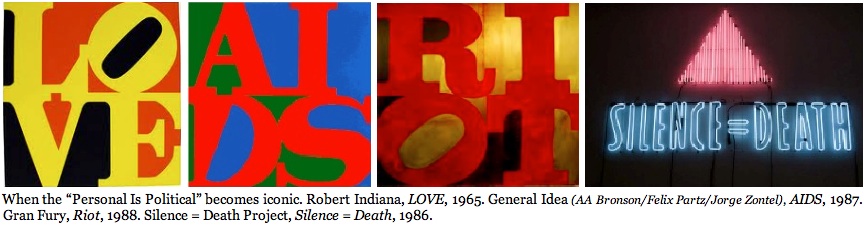

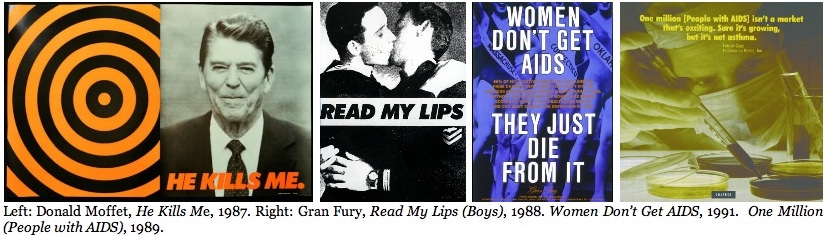

1987 is also the year that the veteran Canadian trio known as General Idea produce the AIDS era's premiere artistic icon. AIDS, a riff off Robert Indiana's 1960s LOVE icon (pictured with the above introduction to this feature), proves itself to be as existentially potent as it is visually bold and conceptually audacious in its appropriation of the 1960's logo of free love. It is fitting that Indiana's LOVE, which was so often interpreted as response to the Vietnam War, should factor into the General Idea's war against the invocation of AIDS as a weapon of sexual discrimination. The relevance of the logo, combined with the tragedy of AIDS being born in relationships of love, immediately ensures that it is taken up around the world as a banner for the campaign to end the contagion, just as the Gran Fury slogan Silence = Death internationally implicates the truly reprehensible, if not potentially criminal, behavior keeping the contagion alive.

General Idea, whose queer art has been internationally exhibited since the early 1970s, would become decimated by the AIDS crisis, with two of its members, Jorge Zontel and Felix Partz, dying only months apart from each other in 1995. Surving member, A.A. Bronson, has since gone on to make an art of post-science shamanism geared for a generation seeking a healing that science has so far shown itself incapable of supplying. (See more on General Idea below.)

1987: Outraged over the government's mismanagement of the AIDS crisis, concerned LGBT individuals in New York City unite to form the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT-UP. Centering their premiering demonstration on Wall Street to protest the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies in the production of AZT, seventeen members are arrested. With more protests planned, the coalition grows rapidly, and the accumulating voices grow into a roar that officials learned they couldn't ignore.

1987: When New Museum senior curator Bill Olander (and a personal friend to me) invited the AIDS-activist group ACT-UP to stage a political action in the New Museum's Broadway window, he didn't know that he had less than nineteen months to live. He DID have a sense that he had put into motion a catalyst for radical change, even though he only saw its wheels turning in test runs.

By 1988, the activist vehicle that broke from that window into the streets came to be known as Gran Fury, after the brand of cars that make up the NYPD cruise and emergency fleet. Comprised of a loose-knit band of ACT-UP visualists--Donald Moffet, Marlene McCarty, Tom Kalin, Mark Simpson, John Lindell, Loring McAlpin and Avram Finklestein -- the team became affectionately known as the propaganda arm of ACT-UP. Finklestein had also earlier organized the Silence=Death Project, which created the iconically scathingly yet enduring and world-renown indictment and admonishment, Silence = Death (pictured with the above introduction to this feature). In real cognitive terms, Fury's propaganda was something called facts, something that the Reagan and Bush administrations eschewed for real propaganda, a.k.a. misinformation. Facts that the media wished under the carpet, Gran Fury retrieved to visibly and textually solidify in the collective consciousness.

Fury's visualizations employed in-your-face tactics every bit as aggressive and effective as any one of The United Colors of Benetton's shock campaigns of the same era. And for at least six years the collective showed all the direct marketing acumen of Madison Avenue's David Ogilvy combined with the art-savvy vision of Golden Square's Charles Saatchi thrown in. In just a short sampling of their combined aesthetic-pragmatic power, Fury left no corner of homophobia left unturned, pulling up and dispensing with the entire carpet of anti-queer bigotry, along with the hidden racisms, sexisms, and gender prejudice of the time along with it. The achieved effect was a cultivation of collective AIDS awareness that heightened the responsiveness levels of HIV positives and their families and friends, medical professionals, government officials and charitable donors. The difference between awareness and activism in the 1980s and the 1990s appear as if night were changed into day, and largely because the ACT-UP demonstrations and the Gran Fury/Silence=Death Project ad campaigns were ubiquitous, at least on the two American coasts.

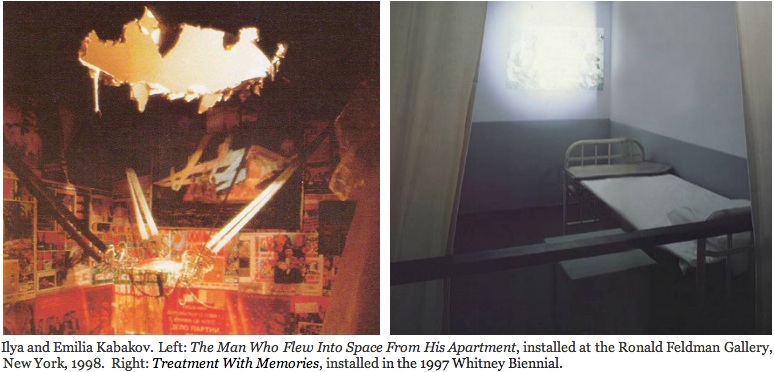

Russian artists always seem to arrive in America with a mythos preceding them, and whether it is Komar and Melamid, Oleg Kulik or Ilya Kabakov, the mythos is a vaiation on the youthful and rebellious individualists who, though swallowed by the Soviet Behemoth, is found so provoke such a bad taste as to be spit out onto the Western shore. But even before we came to know the work of Ilya Kabakove to be a collaborative effort with his wife Emilia, the artist was noted for his reluctance to depict the Soviet Union as a failed Socialist state. Failure, the Kabakovs' works seem to imply, is a natural outcome of a society whose utopian vision came too soon, was too unformed, early, or was simply too big to work, and nature is now correcting the mistake for the Russian people.

The difference is evident from the first introduction of the Kabakovs' work in comparison with their contemporaries. Whereas Komar and Melamid and Oleg Kulik lampoon Russia's marxist-leninist past as well as its unsteady capitalist ventures, the Kabakovs take account in both the comedy and the pathos of the Russian historical narrative. This can be seen by simply putting together two of their installations presented in New York in the years since their arrival. The Man who Flew into Space from his Apartment, installed at Ronald Feldman Fine Art in 1988, and Treatment With Memories, installed in the 1997 Whitney Biennial. Even before we read the titles of the work, The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment strikes us as comic and Treatment With Memories invokes a sense of empathy if not outright compassion. Yet both also reflect the political reality of disappointment with the native country the team found it necessary to leave behind.

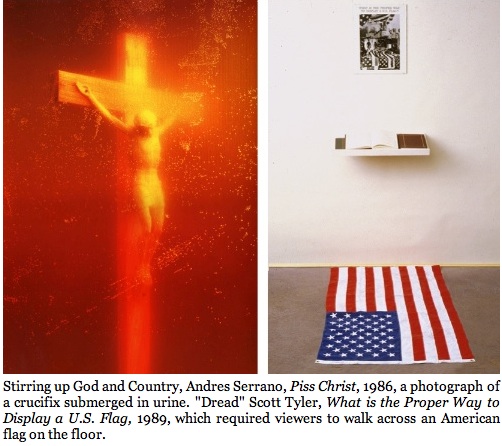

1989 turned out to be the year that we in the artworld found ourselves to be wrong about art no longer being capable of provoking scandal in Western democracies. We found this out when Jesse Helms led Congress in an attack on Andres Serrano's Piss Christ, the now infamous cibachrome photograph of a crucifix submerged in urine, when it was learned that the photo had received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. It was also the year that "Dread" Scott, then known as Scott Tyler, a student at the Chicago Institute of Art, displayed his work What is the Proper Way to Display a Flag? as part of a student exhibition at the Institute. The work included an American flag laid out on the floor. Mounted on the wall directly above the flag were a photograph of various images of American flags and a shelf holding a book in which visitors were invited to record their thoughts about the display. In order to do so, however, they had to step on the flag. The work immediately provoked daily protests outside the Institute and Chicago's City Council soon passed a local ordinance banning flag desecration.

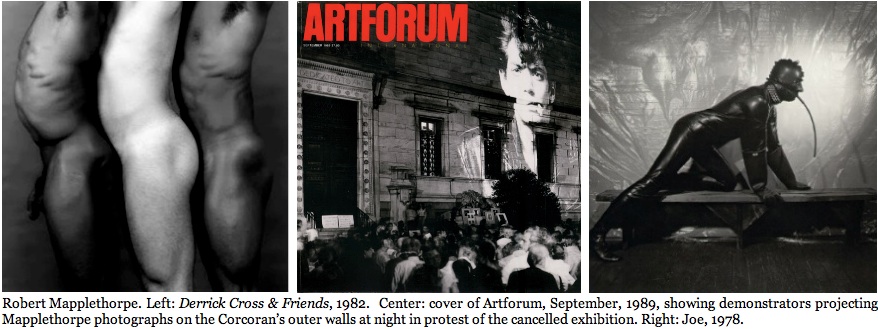

1989 is also the year that a traveling exhibition of photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe scheduled to be hosted by the Corcoran Museum in Washington, DC was unceremoniously cancelled for obscenity by the museum's director, Christina Orr-Cahall, under pressure from the religious right. The public outcry made international news as protestors projected slides of Mapplethorpes's most explicit work on the sides of the museum's walls at night, which ARTFORUM emblazoned on its September cover.

The following April, police and deputies from the sheriff's office ordered the 400 visitors present to leave the opening of the Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective The Perfect Moment at the Contemporary Arts Museum in order to barricade the building and record the evidence on video for later us in the prosecution: the children's portraits of "Rosie" and Jesse McBride from the mid-seventies, on which exposed genitals were visible, plus five works from Mapplethorpe's legendary X Portfolio, which depicts homosexuals engaged in performing S/M practices. On September 28 1990, the so-called Mapplethorpe Obscenity Trial began in Cincinnati. If the district attorney, high police officials, local businessmen, and various anti-pornography groups were to have their way, Dennis Barrie, the director of the hosting museum, could have looked forward to a maximum sentence of six months for the dissemination of pornography. The trial ended with an acquittal on the defense that the photographs were "figurative studies" and "classical compositions," even though the jury was made up of men and women from the working class none of whom had previous contact with art or photography.

Next: When Walls Come Falling Down: Left Political Art Timeline, 1989-2000. Now online @ Huffington Post.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.