Writers struggle to come up with enough superlatives to throw at great dancers like Soledad Barrio. The first time I saw her perform with Noche Flamenca, the company she fronts with her husband, director Martín Santangelo, was at Theatre 80 in Greenwich Village. That was in 1995 and it was one of the most electrifying theatrical experiences of my life. When Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times refers to her as one of the best dancers of any genre working today, it is not hyperbole.

Barrio is able to maintain a throbbing and nearly unbearable tension between containing her seething inner passion and an all out eruption that threatens immolation. She is a conduit, not just for her own passion but for the whole company and the audience as well. Onstage she bristles and crackles like a high tension wire carrying more voltage than it can safely hold. She continues to gather more and more energy with little crescendos that hint at what is to come. As the tension gradually builds, she releases just enough of the accumulated voltage to prevent it from erupting uncontrollably.

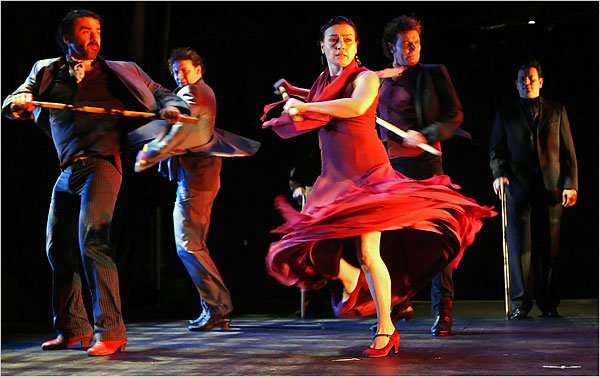

When she finally takes off on a tear of blazing staccato footwork across the stage it all begins to break loose. The whole company is singing, playing guitars, clapping out the rhythm with the palmas, stamping their feet and calling out encouragement. It is incredibly unified and tightly channeled energy that few performers can navigate safely. It is powerful and agonizingly intimate. It is emotionally cathartic and sublimely transcendent. That's the best way I can explain what the Spanish mean when they talk about the meaning of duende in the art of flamenco. The company is performing through Sept. 30 at the Joyce Theater.

Soledad Barrio, photo by Andrés D'Elia

How old were you when you knew you wanted to be a dancer?

Soledad Barrio: I can't remember a time that I didn't want to be a dancer. My first memories begin with dancing. When I was young I danced in the streets, in school, at parties, everywhere. I didn't have formal lessons until I was nineteen. I don't know why I wanted to be a dancer. It wasn't part of my family tradition. We're not Gypsy. We're not from Andalucía. My mother was from Toledo and my father was from Segovia. I was born wanting to dance but I don't know why.

Are you a perfectionist?

SB: Yes. Because I started lessons very late, work is an obsession. I always felt that I was behind and needed to catch up. It always seems to me that I could have danced something better. I never quite feel that anything is completely adequate so I have to try and do more.

Who were your favorite dancers when you were growing up?

SB: I remember seeing Cristina Hoyos and Antonio Gades on the television when I was young. A part of me responded to their dancing. I thought I could dance like that one day. There were so many others, like Manuela Vargas, Manuela Carrasco, Carmen Amaya. I looked up to all of them as idols. My teachers too, of course. They meant everything to me.

Soledad Barrio and Noche Flamenca

What is special to you about flamenco dancing compared to ballet?

SB: Flamenco requires many things besides just the technique. You need a profound understanding of the songs and the guitar. You have to know and be able to communicate with all of these elements on stage beyond your placement and the technique. You also have to understand silence. Flamenco is complex in its relations with all of the elements. Everything can change in an instant because it is always live. You can't separate the music and the dance because it's all part of the theater and it changes every night. It's intensely rhythmic and grounded in the floor. It's also a form in which your art continues to improve as you get older. Experience is very important and valuable in flamenco.

Martín Santangelo: The origins of ballet and the origins of flamenco are two very different things. Ballet was meant to accompany classical music for the pleasure of the royal court. Flamenco is almost the opposite. It was a rebellious cry because people were being persecuted. It was internal, as far as families and community were concerned. Dance, song and music offered relief.

Passion and emotion are at the heart of flamenco -- how do you learn to control it?

SB: It takes a lot of time and experience. It's part of the process of molding and sculpting, first of technique and then the art. It takes many years. The dances have accents and phrasing, it doesn't move in a linear way. The dance, the music and the song all have to work together emotionally and this just takes time and experience to learn to control it.

When I watch you perform I am conscious of you gathering energy from the audience and from the cuadro [the company] how do you do it?

SB: I don't know. I feel during a performance that I am a channel for the energy that comes from the audience and the other performers. I have to be totally concentrated at that time or the energy can escape and it loses its intensity. For me to dance my best, everyone else has to give their energy as well. As a flamenco dancer, you bring everything that has ever happened to you to every performance. You must feel the music and the power of the songs and bring it to that point of ultimate expression.

With classical ballet dancers, you can tell the difference between good and great dancers by the port de bras [arms]. How can you tell in flamenco?

SB: For me it is the same. Young dancers, when they are starting out, they focus on the zapateado [the footwork] because it's so important to flamenco. It's also spectacular and makes an impression on the audience. The percussion and rhythm are essential. Learning the expressive part, control of the torso, the braceo [arms] and floreo [hands] takes many years. For me, it's the highest part of our art. We don't look at it as anyone being the best though, because the dancers, singers and guitar players all have to work together. There are certain individuals, of course, who are very special. What makes them great is how people are able to connect to them. It depends more on what you like because we have different styles of flamenco and it's a very individual and personal art. For me, for example, it's fundamental to dance with my heart. In Spain we say that to be considered a good dancer you must have technique of the zapateado, the braceo and floreo; you must know the whole art: the songs, the music and the guitar; and you must dance with the heart.

Soledad Barrio with Noche Flamenca, photo by Andrés D'Elia

What do you think about when someone brings up duende in flamenco?

SB: I don't really know what duende is. (laughs) It doesn't really have any particular meaning just for flamenco. It is inspiration. It applies to all art. The most important thing is the work. Inspiration can only come to you if you work for it. You have to work hard and the duende will come and go. I saw a dance school in Madrid that had put up a sign advertising that they taught duende. (really laughing now) They were charging a lot of money to foreigners as though it was something that could be taught. You have to have something to say and you have to need to express it.

MS: Federico García Lorca [the Spanish poet] came up with that whole idea after being drunk and not sleeping for three days. He wrote a long chatty essay about duende but Lorca abused the word. Picasso said that you have it when you have it. It comes from working. When you work and work and work, then sometimes everything lines up and comes together. Maybe you had it last night but not tonight. It can happen in the studio when you are alone or on stage with the whole company. You can't control it. All of the elements have to line up at that same time and that only happens rarely. Lorca abused the word. Einstein said the best thing about what we think of as duende: "The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed."

How do you prepare for performances?

SB: When I'm working in the theater I always have to keep some of my focus on the next performance. It's difficult because I am also a wife and mother and that's important to me. And although that makes life more complicated it also helps me. Being a mother is a powerful experience. It gives me inspiration. That's not to say that I think one has to have children to know life but it does add to my performance. I try to compartmentalize and always make sure I save enough energy for the performance. I have to be careful to rest enough.

MS: Soledad also cleans the house for three days before the engagements. Everything has to be super organized and clean.

SB: Well, having the house clean makes my mind clear. Just like animals prepare their nests, I like to make sure mine is tidy. It just makes me feel better.

How does the experience of Noche Flamenca change when you take it from a smaller venue like Theatre 80 to the Joyce Theater?

SB: For me it doesn't change at all. I think it changes more for the audience than it does for me. I've done shows in salons, small theaters and really big theaters. I don't worry about losing the intimacy in a larger theater because I think we have the capacity to break down the wall between the audience and us. I will say that I sometimes get distracted and lose my focus if the audience is too close. When I can see people's faces too clearly I start thinking about them. Some people like to see us closer like in Theatre 80 and some prefer us in the Joyce but it doesn't affect my dancing.

Are you very aware of the audience during a performance?

SB: I am always aware of them. I'm only performing for them. It's a great responsibility. They've all made arrangements and left their work or their homes and they've bought a ticket and this is their time. I always feel like they deserve my best effort. I don't want them to leave without feeling something.

How much improvisation is there in the show?

SB: There are some artists who improvise more than others. You can be a great dancer without improvising. It isn't necessary. It's something that you do because you feel it. I love to improvise when I'm dancing with the whole group because it's much more exciting when I don't know exactly what's going to happen. It's more powerful emotionally. But it's only for very advanced and experienced dancers.

MS: In the group dances it's all choreographed. It has to be. In the solos I like to leave room for improvisation because that's the nature of flamenco. There should always be room for personal improvisation. Even if it means a huge mistake happening, I would still leave room for the improvisation because that's when the most amazing things happen. That's when we find our way out of a disaster and do our best work. Paco de Lucía never improvised until he played with Pat Metheny. That was when he was thirty-four or thirty-five years old and he'd been playing since he was six years old. He said he was terrified at first but now he can't play any other way.

Some of your most powerful moments in performance come during absolute stillness - how does a dancer learn this?

SB: I have the good fortune to work with Martín who has a great understanding of not just dance, but also theater. He explained to me the importance of silence. It's part of the theatrical experience. It's actually more difficult sometimes than dancing and it only comes with years of practice. I also learned by watching Manuela Vargas who was a very theatrical dancer. Flamenco has many different levels of emotion in it and it's part of the culture to leave space between dances. But silence has to be genuinely felt.

MS: This is something we forget about because we get too concerned with filling up all the spaces. To get to those moments of silence there has to be a reason. We have more of those moments now. There are things like death and loneliness that you have to understand. You do all this footwork and then you have to stop because you feel the weight of solitude. I think that to be able to fill those moments of silence, you have to have experienced life -- birth, death, loss -- it's something that you have to go through and then it gives you permission to have moments of profound silence on stage for reflection.

SB: This is part of our culture. You can't separate flamenco from the culture. You have to know the history, the countryside, the trees, the land, the songs and the people to be able to dance it.

Soledad Barrio, photo by Andrés D'Elia