Stanley Tigerman has always had a way with words.

Back in 1979, his witty design for a Museum of Modern Art exhibit called "Buildings for Best Products" was perhaps the most ironic in a group of groundbreaking postmodern showroom designs by Robert A. M. Stern, Michael Graves, Charles Moore, Anthony Lumsden and Allan Greenberg.

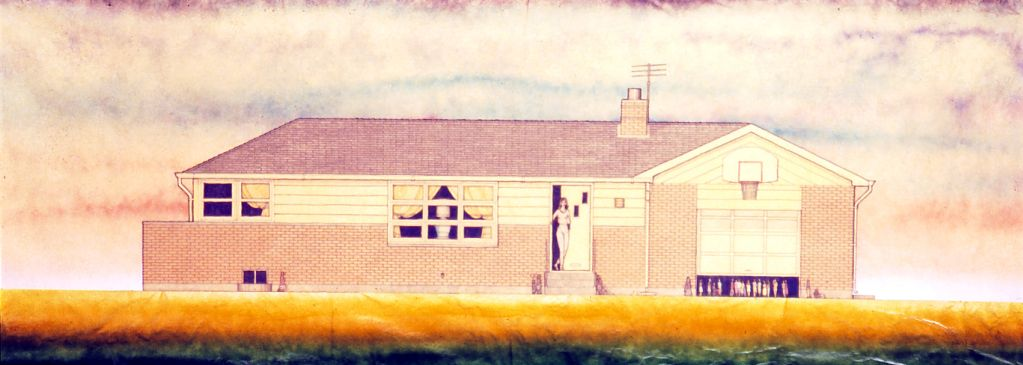

Tigerman called his showroom "The Best Home of All." It was a gigantically out-of-scale ranch house nestled in a suburban sea of smaller ones. A 22-foot-tall housewife as wholesome as Mary Tyler Moore greeted shoppers at the oversized front door. Entry to the catalog showroom was via a permanently broken garage door.

It was, the Chicago urban architect wrote, a "place that could kind of nuzzle up to its little friends, so that when they came out to shop, it would be as if they had never left home." Moreover, he wryly concluded that "all the snotty bastards in the urban United States were simply green with envy."

Today, Tigerman is the center of a major retrospective exhibit of drawings, models and words at the Yale School of Architecture Gallery in historic Paul Rudolph Hall. In the opening talk for the exhibit, titled "Displacement," he made mention of his special gift for language.

"As he said in his lecture at Yale, he's not exactly a person whose tongue has awarded him great commissions," said architect Robert A. M. Stern, who attended Yale Architecture School with him when legendary modernist master Paul Rudolph was at the helm.

Diplomacy, obviously, is not Tigerman's forte. His strengths lie in attempting to use architecture to solve problems -- whether social or cultural -- and to get to the heart of a design challenge to discover a kernel of truth that can be developed with an ironic twist. And as the Yale exhibit demonstrates, he's been quite good at that for a half-century now.

He earned his undergraduate degree from Yale, then went out into the real world for a number of years before returning to graduate school and the tough environment that taskmaster Rudolph had created there. "At the time, Yale was a cross between a Marine boot camp and John Houseman in The Paper Chase," Tigerman said. But the students bonded. "To survive was heroic," he said. "There was one suicide, and several on the shrinks' couches." Still, Tigerman rates Rudolph as his best teacher "He was by far the most demanding -- and even more demanding of himself than others."

And the feeling was mutual, according to Stern. "Everybody was in awe of him [Tigerman]. I think Paul Rudolph was in awe of him," Stern said. "He told me many years later that he thought Stanley was his very best student at that moment at Yale."

Tigerman's work is important because it traces the evolution of 20th and 21st century architecture through all its movements and permutations. "He takes his themes from the reality of American life, in all its confusing complexity," Stern said.

In the late 1960s, he proposed a floating Utopia for Lake Michigan. "It showed a confidence that architecture could solve the problems of the world," said Emmanuel Petit, curator of the Yale exhibit. "He showed whole cities floating on Lake Michigan, connected by steel cables. They could be clipped off in case of nuclear attack, and the cities could float off to Canada. It's a very 1960s theology."

Trained at Yale to embrace the tenets of modernism under Rudolph, Louis Kahn and Josef Albers, Tigerman was also one of the first to announce a break with that movement following the death of Mies van der Rohe.

In a 1978 photomontage titled "The Titanic," he upended Mies' Crown Hall at the College of Architecture at Illinois Institute, positioning it for a plunge into Lake Michigan, and all but declaring modernism dead. It became one of the defining symbols of the postmodernist break with the modernists. "Stanley's drawing really summed it all up, in one breathtaking image," Stern said. "Stanley was trying to shake architecture, but I suppose just as much as anything, to shake himself free of that influence."

He has developed hundreds of large and critically acclaimed projects over the years, many aimed at improving the human experience. There are his 2007 Pacific Garden Mission, the largest center for homeless people in the nation, his 1982 Illinois Regional Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (an AIA National Honor Award-winner), and the 2010 Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, Ill.

In an interesting twist on the concept of positive client relations, it may be that his projects succeed because of his frank language and rough demeanor, rather than despite them. "Most architects try to please their clients," Stern said. "But I think his attitude is like Noel Coward's in one of his plays, that women need to be beaten regularly, like gongs. It's as if Stanley thinks clients need to beaten regularly like gongs -- and then they come back for more."

"Ceci n'est pas une rêverie: The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman" opened on August 22. The title of the exhibit, translated from the French to "This is not a dream," is a play on Rene Magritte's painting of a pipe titled "This is not a pipe." (Of course it wasn't a pipe, Magritte once said -- just try filling it with tobacco).

Petit, associate professor at the Yale School of Architecture, not only curated the exhibit but also wrote the text for its catalog. "His doctoral dissertation at Princeton was on irony," Tigerman said. "He knows the subject, and therefore, he knows me. This exhibit is about his perceptions and his take on me, and it's interesting for me to look at it in that light."

"Tigerman will be remembered for insisting that architecture is not only about aesthetics, but also about an ethical responsibility," Petit said. "It's about different interest groups, the different protagonists with different opinions. It is the duty of the architect to take into account the multiplicity of different voices. It's about dialogue, more than the synthesis that modernists sought to find their pristine forms."

To Stanley Tigerman, though, it's all about the work -- though his words do play a role, also.

"It's as if I'm seeing it all for the first time, and it's marvelous," he said. "Forgive the ego, but it's a show worth seeing."