Louise Bourgeois' Suspension is on view at Cheim & Read Gallery in New York through January 10, 2015. The Heart Is Not A Metaphor, a survey of work by Robert Gober at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, runs through January 18, 2015. For further information link here to the Cheim & Read Gallery and MoMA websites.

Two concurrent exhibitions in New York at the end of 2014 confirm that the Surrealist legacy still informed some of the most vital and psychologically compelling art of the late 20th century. And judging from the rave response to the shows, it still informs, however critically and with any number of realignments in aesthetic and political priorities, a good deal of contemporary art and criticism today. The Heart Is Not A Metaphor, a retrospective of work by Robert Gober at MoMA, and Suspension, the small but captivating survey of hanging sculpture made by Louise Bourgeois at the Cheim & Read Gallery, both derive their power in large part from the near century-old Surrealist project of culling and mediating the Uncanny. Or to put it in contemporary terms, both shows and the response to them prove it is still possible to stimulate and even simulate the Uncanny in a culture tolerant of open sexuality and with little need to secret away representations of erotic drives and desires by vesting them in fetishistic proxies.

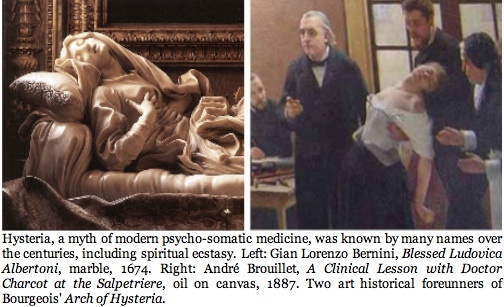

Finessing virtuoso compositions of the Uncanny in an age of open sexuality and within an art world obsessed with The New is no small achievement, given that the Uncanny is a concept derived from the puritanical 19th-century. It was the German Idealist philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling who sought to account for the physical and mental experience of a simultaneous "bewilderment and fascination that both disturbs and arrests our attentions". The Uncanny as a psychological affect was of course refined by Freud with the turn of the 20th-century to suit his theories of neurosis and hysteria. In the hands of the Surrealists of the 1920s and 1930s, and particularly its leader, Andre Breton, the Uncanny became the motivating principle and vision driving the Surrealists to call for an anti-aesthetic revolution seeking the integration of a Convulsive Beauty within everyday life.

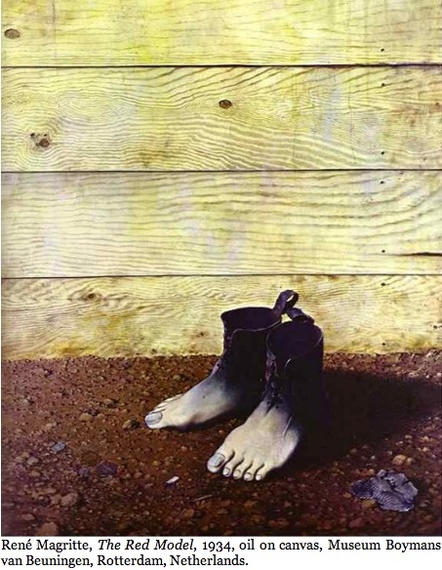

But since the end of the Second World War, psychoanalysts and artists alike increasingly lost sight of the Uncanny even when they employed an "automatic" or stream of consciousness approach like that used by the Surrealists in their work. Yet Bourgeois and Gober clearly concurred (however intuitively or conceptually) with Schelling's observation that the Uncanny is the uncovering of phenomena for which we are unprepared. That alone provided a new source for mining the Uncanny without feeling guilt or fear of an external authority. And as we now look back at Bourgeois' work since the 1960s and Gobers' since the 1980s, we find ample indication that both artists bucked the trend of distancing themselves from Freud enough to re-enact his idea that the Uncanny is the end result of encountering phenomena that strike us as simultaneously "familiar yet strange". Although Freud describes the circumstances whereby people of moral conscience find themselves awakening to desires that they know should be suppressed in accordance with the moral authorities of their social enclaves, he also proposes that even the most conscientious among them unconsciously yet willingly channel those desires into fetishistic (that is protective and disguised) condensations of psycho-somatic energy, while consciously they perceive the fetish to be their desire's (equally protective) effacement in accordance with the presiding authority. Freud believed that we unconsciously protect our forbidden desire for random and impersonal genitalia by transferring that desire to objects that can pass inspection with the moral authorities of the day -- the fetishistic hat whose folds secretly arouse memory of and desire for the furtive vulva; the cigar whose heft fills the void and yearning for the real but absent penis.

Of course, Bourgeois and Gober, like other contemporary artists riveted to late surrealism, had to remake the Uncanny just as they had to revive the Surrealist ideal of an art of transgression and dissent. The fundamental problem was that the fetish lost its power to command artistic production once The Pill and the resultant Sexual Revolution overtook the conservative moral climate of the 1960s. With sexuality now openly discussed and viewed, and with mainstream populations become increasingly acquainted with some aspect of psychoanalysis, the Uncanny was ironically circumvented by its open discussion, even made the butt end of shrink jokes. But then, in the 1980s, the climate of sexual and gender activism provided a new context for the Surrealist revolution, one in which the Uncanny was made to seem obsolete by the increasing elimination by society at large of the guilt that had for so many millennia been attached to socially-proscribed eroticism. But I've gotten ahead of the narrative, as the legacy of Surrealism first has to be experimented with as a vehicle for the mounting activism against the suppressions imparted by new moral authorities who revived a superstitious morality in opposition to abortion, feminism, LGBT lifestyles, and especially all sexual behavior blamed for the spread of HIV-AIDS. As the liberation movements begun in the 1960s now found themselves under attack, the Uncanny was made to once again seem relevant, even if it was now more a rationalization for making an art of dissent than it was a symptom of mounting guilt and suppression of morally proscribed desire. And Bourgeois and Gober were there ready to revitalize the Uncanny as both a motivation for a new Surrealist-styled art and as the instrument of provocation for a new generation of activist artists.

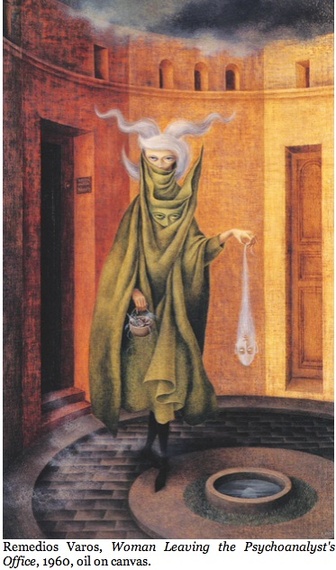

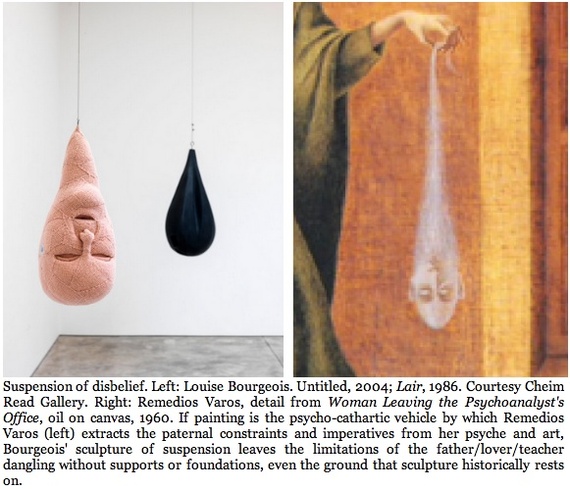

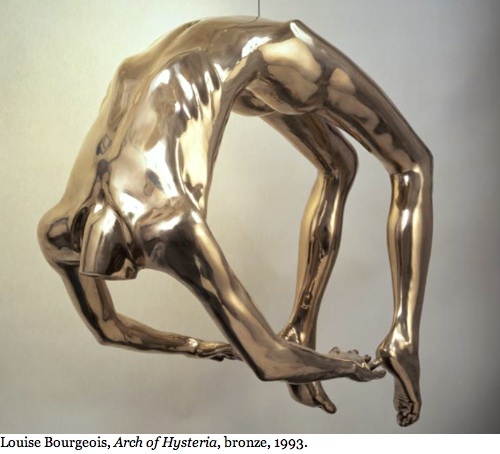

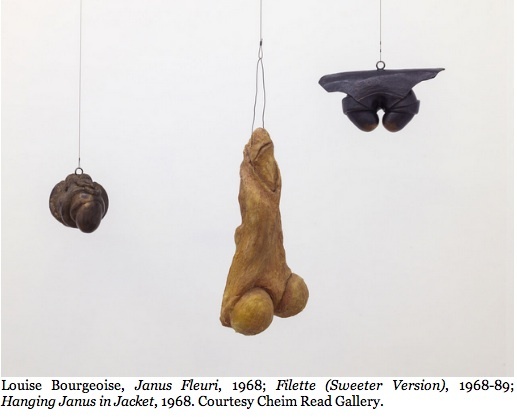

In the Cheim & Read Gallery's isolation of the singular motif of suspension at work in the sculptures of Louise Bourgeois, we're compelled to recognize in Bourgeois' compulsive resistance to gravity a new kind of Uncanny. This is a cultivated and simulated Uncanny that, in its motif and structure of suspension, leads us to assume its debt to one particular artist of the original Surrealist generation. Remedios Varos (1908 - 1963) can be counted among the few historically esteemed women Surrealists, though she is known primarily for her painting Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst's Office, painted in 1960. The depiction of a sophisticated, futuristic woman (or is she a throwback to medieval society?) depositing a large, oozing droplet into a septic vat references the Surrealist's fascination with the spiritualist's living protoplasm. More significantly, Varos paints a scathingly humorous foreshadowing of the feminist tsunami destined to slam the male preserve of Surrealism while signifying the source for the fierce protection of the male homosocial legislation we've come to call patriarchy. In post-Freudian, feminist terms, the woman's psychoanalytic session just completed has enabled her to exorcise her father, or one of her lovers, or all collectively as one dominating male principle hindering her personality, now captured with its memory and power over her transferred within the jism that is finally hers to expel.

Most importantly, like Frida Kahlo, Lenora Carrington, Maya Deren, Meret Oppenheim and Lee Miller (the latter in collaboration with Man Ray), Varos turns the Surrealist project of ferreting out the fetishes protecting illicit desire from the social repression of natural sexual drives and turns it to her own liberating advantage as a woman, daughter and lover. The result is the ultimate feminist retaliation against the law of the father, if not the father and his sperm, that of his banishment as male protector, priest and conscience no longer required or desired. Hereby deposed of (at least until the next therapeutic session) for better or for worse, the casting off of the sperm by the daughter and female lover, with all its mixed emotions and contradictory associations and intimations, is portrayed by Varos as a weight removed from her. The variation on the theme of psychoanalytic liberation that sets this composition apart from the dictates of Freud (yet another father) is that Varos' rendition of the Uncanny is not encountered upon the suppression of desire, but by her desire's liberation fortified by the psychoanalytic reinforcement that enables her to free herself from a repressive moral and sexual authority.

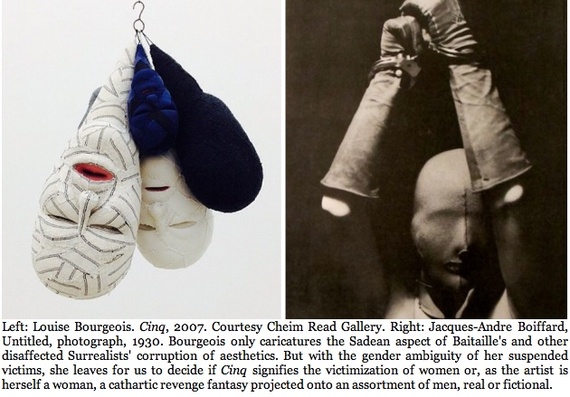

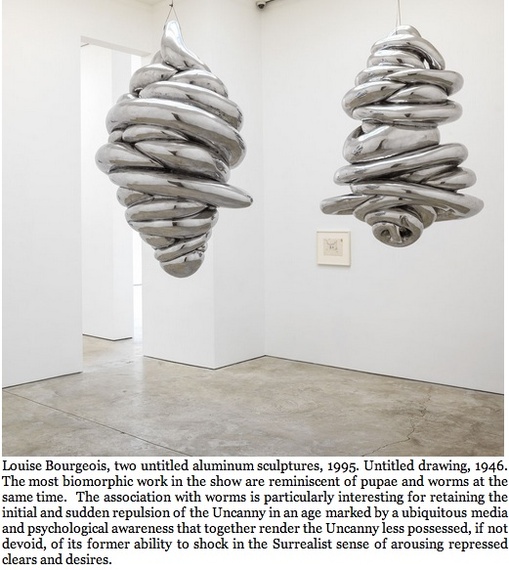

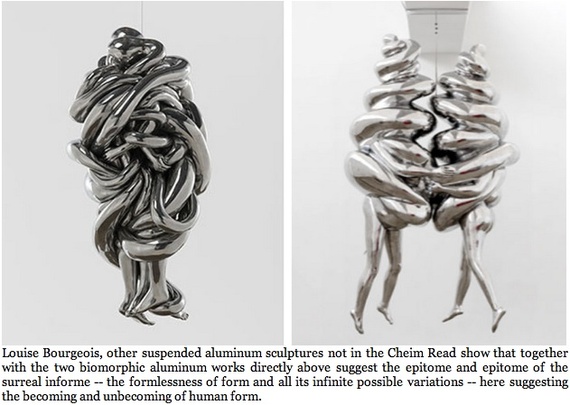

If Varos begins the project of freeing herself from the iconography that limits women to being mere repositories and incubators for the male's sperm and the complex of desires that men are taught to project onto her, Bourgeois takes this project to its full realization. The difference is that Bourgeois by all appearances transfers the project of self-liberation onto the art world and the project of making art herself as a woman artist and as a legatee of a Surrealism that, as the canon of art history has framed it, fetishizes the bodies of women in the most absurdly contorted and demeaning object-avators. If Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst's Office inverts the traditional Oedipal/Electra drama in its depiction of a daughter releasing herself from the social valuations of and expectations imposed by her father and lovers, Bourgeois' suspensions expand on the Surrealist informe (that is, the formlessness or preform of form) by freeing form and formlessness both from the Surrealist project of fetishizing women to one of women envisioning and embodying the suspension of the many complexes exorcised, drawn and quartered and hung out to survey with satisfaction before being discarded and destroyed. Many of Bourgeois' suspensions even resemble, if not mimic, Varos' droplet, a mimicry which reinforces at least this viewer to regard Varos as anticipating the significance that body fluids would come to take on both as a motif of formlessness in flux and a legitimate physical material that so many feminists introduced into the vocabulary of the 20th-century modulation of form and informe.

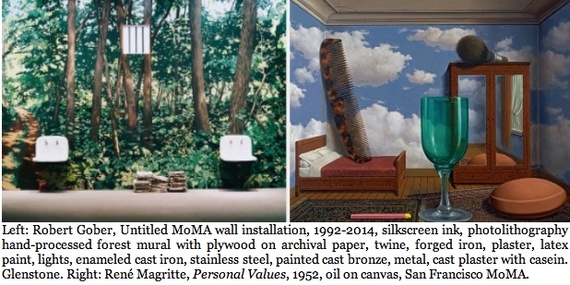

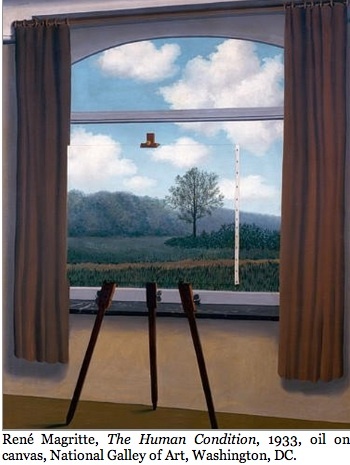

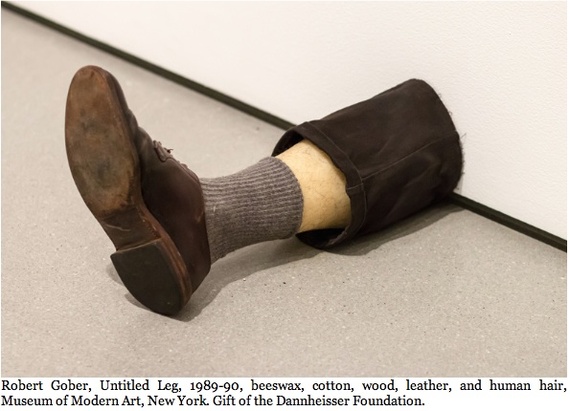

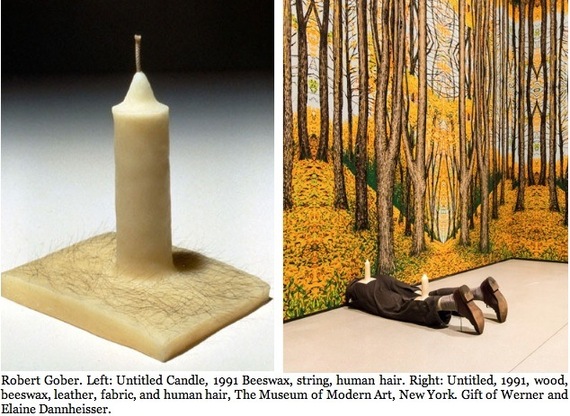

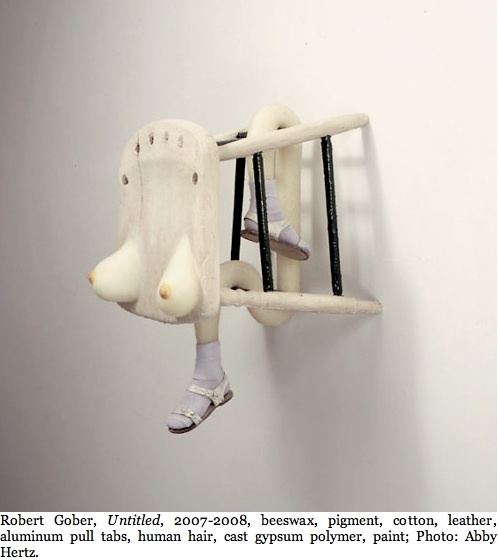

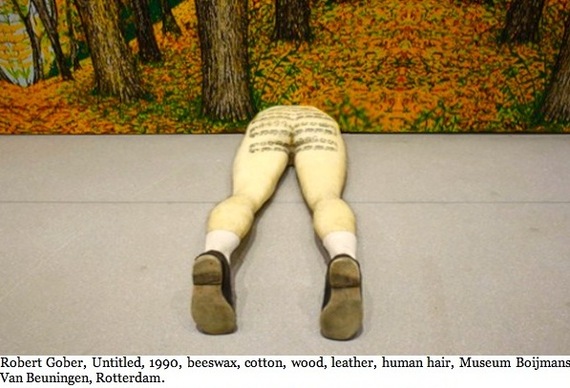

Gober even more prominently and successively exhibits his debt to René Magritte (1898-1967) for the simulated amputation and isolation of human body parts and their grafting to inanimate objects while partitioning them off from the world with walls that formally define and arrest vision even as they reference the plane of the painting on which they appear. Magritte particularly favored indicting the trompe l'oeil painting, what he regarded the most treacherous of images, by framing it within the real painting of his making so that it functioned punningly "parallel" to the real picture plane. Gober three-dimensionally puns on Magritte's pictorial pun on three-dimensional space in a three-generational media installation. The third media generation consists of Gober's screen-printed wallpaper-paintings with which he covers the walls of the gallery to invert the illusionism of trompe l'oeil painting with computer software. This mechanical process introduces the second media generation, the trompe l'oeil of a hand-painted trompe l'oeil picture of the first generation medium, a real space either depicted or imaginatively evoked. In the real space, the trompe l'oeil painting ironically makes the wall "disappear" into the painting in deference to the way that Magritte makes both a landscape painting and a window it stands before disappear into the painting-within-a-painting. Just as Magritte transubstantiates the sculptural illusion two-dimensionality, Gober transubstantiates the painted illusion three-dimensionally, while also transubstantiating the hand-painted process with computer software. Whereas Magritte's painting effects an illusionistic mimicry of depth, Gober's wallpaper effects a computer generated double-mimicry of painted flatness mimicking real-life dimensionality.

Art historian Pepe Karmel in his essay for the exhibition, Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has treated this inversion further, and on which I can't hope to improve. "What recalls Magritte in Gober's work is not just the juxtaposition of incongruous items, but also the obsessive attention to the material qualities of things and the revelation of an ominous aura surrounding everyday objects. Converting the literal space of the gallery into a symbolic arena, Gober extends and transforms the tradition of minimal and postminimal installation." With respect to Gober's 1991 installation at the Jeu de Paume and his 1992 installation at the Dia Center for the Arts, both of which covered all four walls of the exhibition space from floor to ceiling with elaborate paintings of forest settings, Karmel writes that Gober's decision "simultaneously to recreate this trompe l'oeil view and to subvert it recalls the canvases in which Magritte depicted a landscape painting set on an easel in front of a landscape, with the view on the canvas merging seamlessly into the "real" view around it. The breakdown of the border between representation and reality induces a kind of mental vertigo."

With such steep investment by both Bourgeois and Gober in the original Surrealist movement, it is off-putting to find nary a word has been written about either the MoMA or the Cheim & Read exhibitions in terms of the sustained revitalization of the Surrealist aesthetics of the Uncanny and Convulsive Beauty that both shows promote, or more significantly, that the two artists throughout their careers demonstrate great deference to the original Surrealist generation. But this has been the pattern over the decades. Despite the two artist's open admiration for the original movement, the art world heaps accolades on Bourgeois and Gober while exhibiting a resistance to their Surrealist identifications, if not wishfully exorcising those identifications outright, while preferring to squeeze the artists uncomfortably within the post-Conceptual and post-Structuralist media- and irony-obsessed artistic paradigms that have taken hold of art since the 1970s. From the 1980s on there has been an air of anxiety surrounding, if not an unspoken proscription of, the association of the original Surrealist movement in relationship to Bourgeois' and Gober's art. In the 1980s, the anxiety was new and subtle, given that in the 1950s and 1960s to have one's art linked to Surrealism was a mark of pedigree, and as late as the 1970s artists such as Eva Hesse and Jonathan Borofsky could be discussed admirably in Surrealist contexts and terms. But from the 1980s on into the present, the poststructuralist and conceptualist biases that dismiss Surrealist concerns as unrealized and outdated has held sway.

Such depreciation is evident in the wall texts educating audiences at MoMA's Gober retrospective, which pointedly shun any mention of Surrealism, Freud, the Uncanny and Convulsive Beauty. (The term 'surreal' appears but once in the MoMA wall texts, but as an incidental adjective that functions as one more synonym for 'strange'.) Although the texts play up the morally and emotionally lacerating significations abounding in Gober's work, they downplay any flattening of the emotions and sentiments so to allow the sense of loss and finality to be wielded as some chisel into the poetic and aesthetic stone of life, the convulsions that carve into relief some frieze of catharsis full of highlighted foregrounds presiding over deeply-shadowed furrows and crevices that the Surrealists would see as the monuments of Convulsive Beauty. Unlike most people, the Surrealists expressed an appreciation for the poetic injuries afflicted by the passage of time. No doubt the curators, Ann Temkin and Paulina Pobocha felt restrained by respect for those who lost loved ones to HIV-AIDS, despite that such losses were presumably on Gober's mind when he made what may be the most uncanny of his work during the devastating years of the crisis.

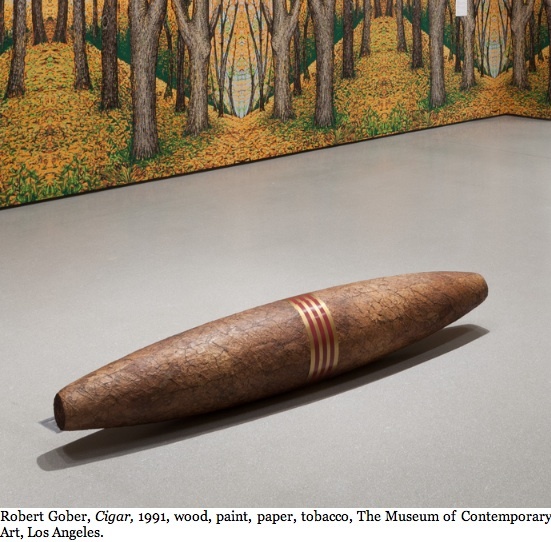

Yet the texts also reflect the curators' strivings to make the work's ethos contemporary in a way that the Surrealist association encumbers. Instead of Freud, the curators on one wall text cite Winnicott, a post-Freudian psychoanalyst who came into prominence during the 1980s with a more thoroughly-scientific grounding favoring a clinically observed and tested basis to the theorization of the personality and its afflictions, while rejecting the largely speculative formation of Freud's conceptual metapsychology. Even in the gallery that features Gober's giant and largely literally-modeled and painted cigar in a central spot on the gallery floor, Freud goes unmentioned in the wall texts.

This is no small transference of valuation. Replacing Freud (and more pointedly, if discreetly, Lacan, who retains much that is essentially and structurally Freudian while having a profound impact on artists of a poststructural bent) with Winnicott, as the psycho-ideological center of contemporary American art imparts the sense that Freud is too obsolete to mention as a result of feminist, queer and transgender dissent against his hetero-patriarchal model of human health and disorder. It was Winnicott, after all, who introduced the anti-essentialist strain of analysis when he argued that it was the environment, not the complexes ingrained in the human subject, that was the topographical framework for the development of the individual personality and his or her integration of the human drives with presiding moral codes. In short, while mention of Winnicott's ideology is more in line with the requirements of feminist and LGBT sexual, moral and political re-socialization of sexual and gender differences even in the context of readdressing Surrealism, the neglect of Freud in a commentary on an artist so indebted to him, even if only through the Surrealists, can only be taken as willful cultural amnesia.

But cultural amnesia is not the correction required for the original Surrealists' suppression of gynarchy and homosexuality. While it is true that there is no mention of gender, sex, or their fetishization anywhere in Andre Breton's Surrealist Manifestos of 1924 and 1929, this omission, when considered together with the well-known homophobia of Breton, Dali, and lesser-known Surrealists, should be added to the long list of critiques proclaiming Surrealism to have failed on several fronts. Mention of the lapse in the MoMA exhibition would embolden Gober's standing for succeeding where certain of the Surrealists failed -- most notably in terms of serving as an avant-garde vehicle dedicated to the overthrow of traditional categories of art. For Gober achieves the Surrealist agenda of politicizing art by doing the very thing the Surrealists neglected in their art. And that is representing the inner, personal experience of the Uncanny with a new and liberating visual language that is both emotionally therapeutic and politically primed for inspiring social action.

We can more easily forgive the commercial gallerists for lapsing into ahistorical accounts geared to distance their artists from historical legacies that are the art market's version of audience poison, while also making new artists appear significantly, if momentarily, perpetuating some semblance of the avant-garde to close the sale. After all, the power of art to effect scandal among the cultural audiences of the 1920s and 1930s came to seem quaint if not cliche for relying on a simplistic and pseudoscientific psycho-somatic catharsis, especially as American and European audiences grew better educated and more sophisticated over the decades. And what can the artists and promoters of art do when the legitimacy of the avant-garde no longer rests on the Uncanny of Surrealism, given that the the uncanny transference the Surrealists were most interested in -- that of the fetish -- can only be vitally aroused in a climate of repression. Eliminate the cultural and moral suppression of the nude and sight of its genitalia, and there is no need for the kind of fetishization that produces at least the erotic Uncanny in the culture at large. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, with explicit eroticism in art, entertainment and pornography disseminated throughout Western civilization, artists still attached to the formal innovations that grew out of Surrealism found they only had dissent against the political repression of women and LGBT individuals in the mainstream to vitalize Surrealist and other varieties of culturally transgressive productions that ironically depend on moral and political suppression for their ideology of revolt.

But such rationalizations can't justify the historical amnesia of a world-class museum dedicated to recording and delineating current canons of significant artistic production and taste no matter how much the museum exhibition and collection depends on the endowments of collector trustees who arguably benefit from rearrangement in the historical record. The lapse is especially curious given that such recent and renown museum exhibitions as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's 2007 spectacular, Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images, and the Centre Pompidou's extensive survey of sculpture in Le Surrealisme et L'Objet of 2013-14 both pivoted on the thesis that much contemporary art remains crucially indebted to Surrealism.

The LACMA and Pompidou shows do shed light on one possible rationale explaining why some curators, gallerists and collectors involved with the work of Bourgeois and Gober might wish to circumvent the climate of scandal that the original Surrealist productions sought out and produced. For however ingenious Bourgeois and Gober have been in revitalizing the Surrealist Uncanny in their art by aligning it with the culture of contemporary dissent, their art has never been particularly given to provoking scandal as much as it has been humorously, poignantly and politically instructive. This is in part due to the artists' restraint in representing or depicting explicit sexual acts. Moreover, however uncanny their use of the nude and genitalia is, the appearance of genitalia and fetishes in their work is simultaneously amusing for conveying formal puns (in deference to Freud, Magritte, Varos) and aesthetically conformed to compositional harmony. At the most, Bourgeois and Gober are preoccupied with the absurd association and arrangement of genitalia and fetishes which compensate for the more simple arrangements that were sufficient to produce the Uncanny for earlier generations.

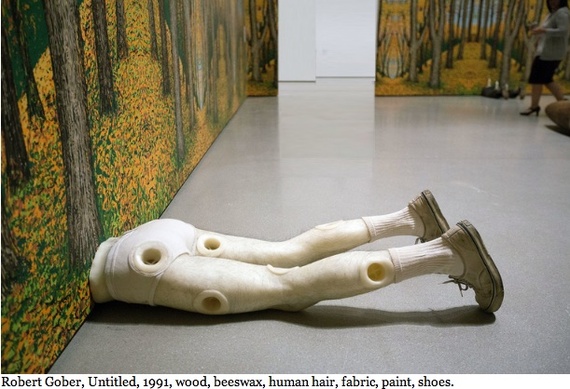

Although Gober has made a series of work with children's shoes and childlike simulated legs that suggest disturbing, even criminal, scenarios, they retain enough ambiguity to prompt us to question whether the dark thoughts aren't being projected onto the work by we, the viewers, rather than being signified by the artist. Considering their overall productions, in their steady recourse to sexual and narrative ambiguity, Bourgeois and Gober, though undoubtedly transgressive toward conservative sex and gender norms, neither veer close enough to pornography to be considered children of Georges Bataille, Breton's ideological and theoretical rival whom many of his contemporaries regarded to be a pornographer. In fact, Bataille's extreme disaffection with Surrealism, which he saw surrendering to the attentions of the bourgeoisie, spurred him on in his mock elaborations of a modern society that would be best suited by returning to an orgiastic, even Sadean, practice of pagan ritualistic sexual abandon. In terms of shock value, both Bourgeois and Gober have been surpassed by a succession of contemporaries, such as the Vienna Actionists, Carolee Schneemann, Karen Finley, Andres Serrano, Lynda Benglis and Robert Mapplethorpe, all of whom truly scandalized recent middle class audiences while awing more seasoned culturophiles with the lengths they would go to in ensuring their art (and in Benglis's case an Artforum ad for an exhibition) was transgressive. This increased inability to scandalize the Western liberal and secular middle class audience inevitably accounts for a wishful disassociation with Surrealism among gallerists, curators, critics and artists who (ironically) yearn nostalgically for a renewed avant-garde with teeth that bite the hands feeding it.

The plight of Surrealism's failure to scandalize today was central to the exhibition, Undercover Surrealism, mounted in 2006 at the Hayword Gallery in London by Surrealism scholars Dawn Ades and Simon Baker. The show was provocative enough to prompt The Guardian's Mark Hudson to summarize its contemporary context. "If the relevance of Surrealism itself is generally agreed to be at an all-time low, the influence of the deviant branch represented by [Georges] Bataille and [his journal] Documents, seems inexorably on the rise. A whole generation of younger would-be transgressor artists -- including the Chapman Brothers, Thomas Hirschhorn and Paul McCarthy -- cite Bataille as an influence." Indeed, with Breton and other Surrealists in disrepute, and with the spread of sexual liberalism, Bataille finally and posthumously attained the appreciation he'd been denied by earlier generations during his lifetime for promoting what was dismissed as sheer pornography. With Bataille's unbridled embrace of a new erotism in mind, scores of artists from the 1980s onward sought to locate a new politics of surrealism (now written with a lower case 's' to distance it from the original movement while signifying surrealism's new ubiquity in culture) and surrealist-derived artistic activism within a definition of convulsive beauty that, stripped of its function to sublimate art, breaks down the values of convention -- such as gender and cultural identity -- while seeking to deepen our comprehension of power and sexual relations in the world.

And yet Bourgeois and Gober have made art that has proven to sustain interest despite their imposition of aesthetic restraint. Of course so did Magritte, Dali, Ernst, Di Chirico, and perhaps the greatest of Surrealists, Frida Kahlo. None indulge orgiastic displays, but all issued powerfully evocative and provocative compositions. Only Kahlo brought politics into her panting to the extent that Bourgeois and Gober bring it into their sculpture. But Bourgeois and Gober also bring to their sculpture the elegant, whimsical, metaphysical and morphologically astute punning on a level with Magritte, Dali, Ernst and Di Chirico. Still, it is Bourgeois' and Gober's aestheticism that keeps curators and commentators coming back, while making them wary of burying the artists prematurely in the Surrealist family crypt.

Conversely, for artists and audiences unconcerned with the fickle art market, it is memory of how Bourgeois and Gober throughout the 1980s and 1990s made their art of dissent personal in a way that was foreign to Breton and Bataille that is most compelling. Bourgeois let it be known that in her life the suppression of the feminist principle began with her father and continued on through her marriage and motherhood. Gober progressed from a celebration and pride of coming out as a gay man to finding his hedonism overshadowed and crushed by the rapid spread of HIV-AIDS and its neglect by the government and medical establishments. It was the most natural of transferences to project such severely limiting yet personal alienations and emotional lacerations onto an artist's parent Surrealism, especially given that artists such as Bourgeois and Gober could feel let down if not betrayed by those Surrealists who became known for an obsessively exploitive objectification of women's bodies and or a salient and virulent homophobia. It is for such a complicated legacy of contradictions that the activist artists of the 1980s and 1990s took up the project of effecting a critical psycho-sexual revitalization of the Surrealist Uncanny. And lest we forget, the artists who were waging the most virulent dissent against the institutional and popular agents of political suppression between the 1960s and the 1990s weren't the underclass that Bataille favored. It was the children of the middle classes who, during the 1970s brought the Vietnam War to a close, and during the Reagan-Bush administrations of the 1980s and 1990s brought the issues of sexuality, gender, reproduction, ethnicity and race to the streets, to the media, to the academies, and to the art world. In terms of revolutions, the dissent of the middle classes proved ultimately to be both more contagious and more effectual than anything dreamed of by the Surrealists' proletarian revolt.

There is also that aspect of the Surrealist legacy that informed the aesthetics brought to the art of dissent. However else the original Surrealist Revolution failed for being so successfully subsumed into and sublimated by the mainstream media, it directly and positively was the foundation on which all subsequent aesthetic theories and formal strategies of mid- to late-twentieth century art were elaborated. Abstract Expressionism, Combine Art, Pop Art, Happenings, Minimalism, Performance Art and Conceptualism all quoted, appropriated and departed from Surrealism. On the downside, such a profuse diffusion of Surrealist principles, lessons and exercises ultimately became so diluted within the art market that Surrealism was seen to be exhausted. As it turns out, Bourgeois's feminism and Gober's queer and AIDS activism were the catalysts timed to the resurrection and revitalization of the Surrealist Uncanny as a potent and salient agent of signification required to effect enlightenment through an art of aesthetic activism.

And yet it isn't merely for their dissent against late 20th-century political establishments that keeps Gober and Bourgeois from being reduced to the status of second- or third-generation surrealists who academically perpetuate the Uncanny or Convulsive Beauty. For both artists, the Uncanny and Convulsive Beauty were still to be arrived at through the working out of an individual's liberation from whatever is the current agency of cultural repression, just as it had been for the original Surrealists. The difference is, the potency of their work was now equally to be found in their renewed yet conceptualized aesthetics. And really, the Surrealist always retained both an aesthetic eye and a wry sense of humor, however much Breton proclaimed otherwise. The very fact that we are aroused by or attracted to some aspect of the Uncanny is due to the faint glimmer of the desire being repressed, and desire is a response to an aesthetic stimulus, however much the stimulus is attached as well to the sexual drives.

Of course Bourgeois and Gober retain the erotic in their work sufficiently to mingle with the beauty and humor that enhance it. The return to visual aesthetics and linguistic and formal puns thus reorients Bourgeois' and Gober's location of the Uncanny not in the activism against, and liberation from, the cultural and moral agency of repression, but in the awakening to a forbidden beauty and eroticism that from the start impels us to strive for the parity of suppressed individuals that may include us or are the objects of our desire. Surrealist theory always insinuated the experience of the Uncanny is the first step to enacting liberation from repression. For the original Surrealists that liberation was glimpsed (or wished) largely in the future. By contrast, for Bourgeois, Gober and others who grew with the liberation of feminist and LGBT imperatives, there was a tangible sense that liberation was growing more salient with each social, moral and legislative victory. It remains to be seen if the Uncanny disappears with liberation, political surrealism and the Uncanny will also wither away, as it seems to be doing. On the other hand, each new advance in civilization brings with it new challenges and authorities that can redraw the map of morality and politics while suddenly blocking and cutting off the avenues of desire and its gratification so that a new Uncanny comes to the fore. It is a perverse pastime to be nostalgic for the Uncanny when the Uncanny requires the suppression of our desires to flourish.

If Bourgeois and Gober can be regarded as both Surrealists and as post-Surrealists, it is because they are virtuosos in their modulation of the infinite capacity of the informe that is to be found in nature or culture, often as some identifiable form with or without human utility, and within which the artist sees some previously unrealized meaning or resemblance. (Think of the way that Man Ray and Lee Miller saw in the fetishized body of woman the informe that with some contortions can be made to resemble the penis. Or in a less sexually-charged example, the way that a tribal African sculptor saw in a tree branch the informe of the human body or face to be released with the sculptor's chisel.) In much of Bourgeois' and Gober's work we can see the Surrealist employment of the informe overtaking the fetish in art. This is because their informe is freed of the fetishization of the male or female subject by the open display of the respective genitalia

Bourgeois and Gober make conscious what Freud described as the unconscious effacement and displacement of the genital object, both the phallus and the vulva, by resisting the social convention of camouflaging the libidinal desire within a non-genital object made to resemble genitalia or some other body part. In place of the fetish, Bourgeois and Gober graft the recognizable genitalia to objects. The resultant conflation isn't a fetish because the fetish simultaneously stands in for the genital desired even as it hid the genital from view -- or more accurately effaced the genital form while retaining only a formal if discreet resemblance to the genital while taking up its erotic charge. Both artists are keen to the wisdom that the fetish only has power in a culture of repression. In a society that openly displays sexuality either physically, or through the proxy of art and pornography, the fetish is without its required function of transferring the charge of the genitalia onto an object and essentially is thereby voided. Whereas the fetish is carried on in secret and shame, Bourgeois' and Gober's art enables us to openly gaze at genitalia grafted to objects whose purpose is to be sublimated by society as art.

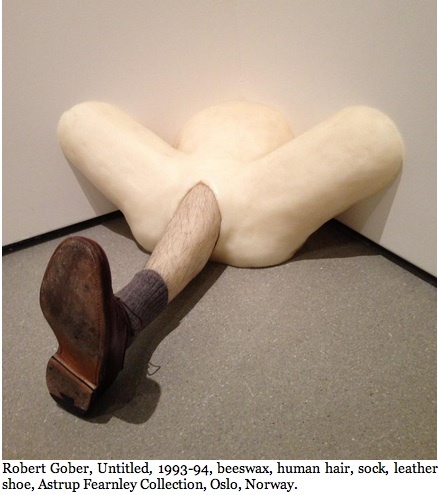

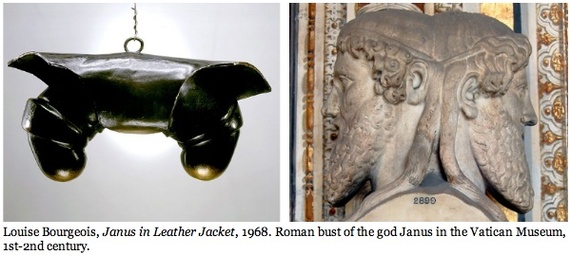

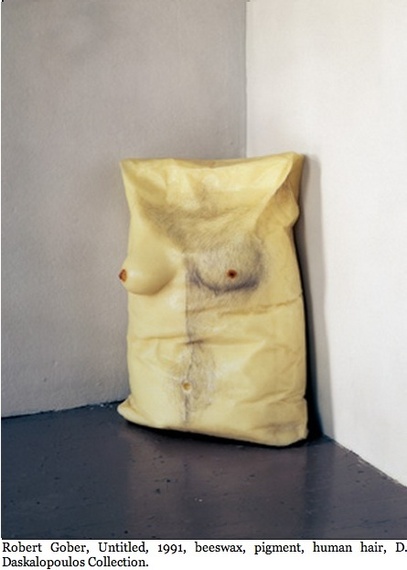

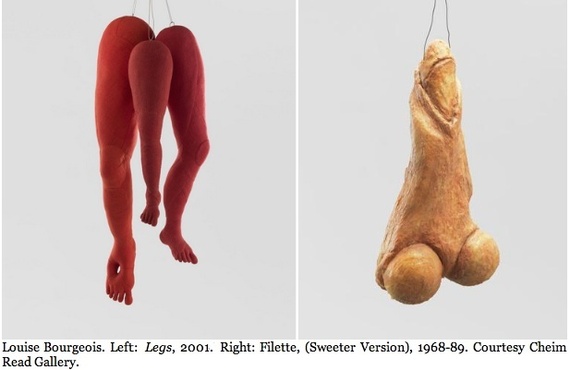

In a work such as Janus in a Leather Jacket, 1968, Bourgeois subjects the phallus to the same objectification and fetishization as the Surrealists did to the bulbous inform of the female breasts and buttocks. After all, if women's breasts can be grafted onto a beast such as the sphinx, griffin or harpy, as they were since antiquity and of whom the Surrealists, like the Symbolists before them, quoted, why can't an imaginary object also receive male genital signification? In Filette, Bourgeois took up the challenge with an explicitly and full-fledged mythopoetic bronze phallus cast decades ahead of its time, while reaching back in time for a male mythical prototype to mimic. In Untitled Candle, 1991, with its simulated pubic hair or any of the 1991 beeswax leg and buttock sculptures with candle appendages, Gober condenses desire for the male body with mock fetishistic candles that parody the Surrealist's simulated condensation of arbitrary and dissociative objectification of the female body. These and other of the artists' works simultaneously submit to the Surrealist scrutiny of middle class conventions and turn the lens of scrutiny back at the Surrealists for their omissions of bias that betrayed the alleged automatism that was proposed by them to replace conscious choice as the arbiter of Surrealist taste.

In this regard, both Bourgeois and Gober expose the prejudice behind the myth of the male Surrealist of the early and mid-20th-century by going back to the basic constitution of Surrealism, beginning with its principles of the informe and the fetish. By extrapolating the male and female genitalia and wielding them openly, instead of discreetly as did the oft-time stunningly prudish Surrealists, Bourgeois and Gober recharge the objectification of women's and men's bodies by incorporating the phallus imagery largely excluded from mid-20th century Surrealist production out of homophobic concerns. In this respect, the two artists independently take Surrealism to its logical conclusion in ultimately collapsing traditionally-imposed gender and sexual representations compatible with feminism, queer and transgendered valuations that ultimately free the inform and fetish from their former, predominantly hetero-male valuations. In other words, Bourgeois and Gober achieve for all men and women what the Surrealists by and large only accomplished for heterosexual men. They render the whole human subject and its fetishistic objectifications into one holistically destabilizing visual and conceptual ambiguity that makes all alternative readings of non-invasive sex and gender equal in the eyes of the artist.

The End

On December 31, 2014 the author added the image of art historical renditions of presumed hysteria by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and André Brouillet, and the image of René Magritte's The Human Condition. The original post did not contain their examples.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook.