Providing medical care in a war zone is never an easy task, but doctors in Syria's opposition-held areas face particularly extreme challenges as their hospitals become targets for bombing campaigns. Michele Heisler, a researcher and professor at the University of Michigan, spoke with Syrian doctors on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights. She tells ResearchGate what she learned. In what capacity did you conduct the assessment you published in the New England Journal of Medicine?

Michele Heisler: My coauthor Elise Baker and I went to southern Turkey last year, where there was a meeting of physicians from Aleppo, the largest city in northern Syria. Because it's opposition controlled, eastern Aleppo has experienced frequent attacks. The main aims of our study were to figure out what the situation with health infrastructure there was and how health professionals are managing.

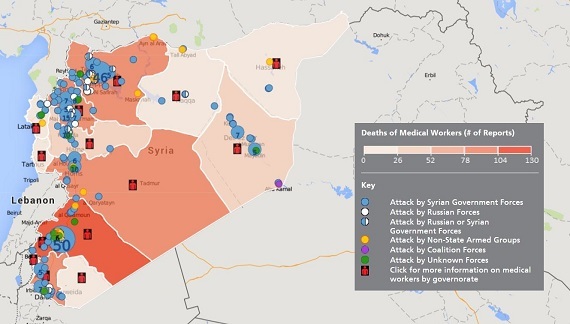

We conducted the project on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights, which documents attacks on health professionals and medical facilities, violations of medial neutrality, throughout the world.

What kind of medical facilities were operating in Syria at the time of your visit?

Heisler: There was a range, from very sparsely equipped and staffed medical points that work primarily to stabilize and triage patients and send them to better-equipped facilities, to hospitals with surgical capacities. In Syria it really varies, because in the government-controlled areas, there haven't been aerial attacks on hospitals. But certainly in places like eastern Aleppo all of the facilities are pretty under-equipped.

Who is staffing them?

Heisler: There are doctors, nurses, medical students, medical volunteers, all working very long hours and beyond their areas of expertise. You have pediatricians who've had to learn how to do surgery and general surgeons trying to do vascular surgery. One general surgeon explained that he can save a life by cutting off a leg, but with the sadness of knowing the leg could have been saved by a surgeon with different expertise. Lives are being saved, but there's no physical therapy, and almost no mental health resources for the very high rates of PTSD.

What types of attacks are medical facilities experiencing?

Heisler: In opposition-controlled areas, the medical facilities are being directly bombed by Syrian government forces and heavily bombed by Russian forces as well. Some attacks are with missiles, bombs, and rockets delivered by war planes. The most gruesome attacks we outline in the report are with barrel bombs, which are packed with nails and all sorts of things that will shatter. They tend to explode throughout people's bodies, so the types of injuries are really horrific.

Physicians for Human Rights has also documented some attacks on medical facilities by opposition groups and by ISIS, but these attacks are much fewer. Through February 2016, PHR documented 358 attacks on medical facilities, and 91 percent of these were by Syrian government and Russian forces. Last month, Vladimir Putin announced the withdrawal of Russian forces from Syria. How has the situation for healthcare workers developed since then?

Heisler: Russian forces have not actually withdrawn from Syria. While flying some warplanes back to Russia, they shipped in more advanced helicopters, which are now being used to launch attacks. At the end of March, Syrian government forces shelled the hospital in Latakia and a nearby physiotherapy center, forcing them both to close. And just April 13, an airstrike killed the health director for the region as he was leaving his hospital in Hama. His death is an incredible loss to Syria's medical community.

"It became clear the red cross was more a target than a shield"

Is it typical for medical facilities to be targeted in conflicts? How does current case in Syria compare to historical precedent?

Heisler: What we're finding is that this is increasingly becoming the new norm. Since the Geneva Convention in the late 1800s there was a period in which medical neutrality was largely observed, though there were other atrocities certainly. But today we're seeing increasing violations. Other places where medical facilities are clearly being targeted are Yemen, Afghanistan, and South Sudan. Still, in terms of the scope and scale of attacks, there really hasn't been anything like Syria, where attacking healthcare facilities and killing doctors is really part of a systematic strategy.

The Geneva Convention states that "zones established to shelter the wounded, sick and civilians must not be attacked." Is that a realistic rule in wars where it's hard to tell who is civilian and who is not?

Heisler: When Physicians for Human Rights started looking into this issue, we expected to mostly see collateral damage. But as we started sifting through all the evidence, it became clear that it usually wasn't. Most of the major hospitals stand alone, and everyone knows where and what those buildings are, just like a major hospital in any large city around the world. We even looked at satellite imagery to rule out the possibility that there were mobile military targets like armored vehicles in the area. The attacks on the medical facilities are clearly not collateral damage. So yes, the simple answer is that it is a realistic rule, and it's not being followed.

Is there anything the doctors on the ground brought up in interviews that really stuck with you? Heisler: There is incredible inspiration in the motivations of the physicians. One of the physicians I spoke with had actually gone to Germany with his family and was going to have the opportunity to continue his advanced training in pediatric surgery, but he came back. He said he thought, "I am Syrian. I am from Aleppo. How can I live with myself as a doctor if I don't go back and help the people in my city?" We're saying, "Gosh, how can you do this?" and they're saying, "How could I not do this? I'm a doctor." Many of the people we interviewed told us about a colleague--one of the few female physicians still there--who hasn't left Aleppo once since the beginning of the conflict. She says women will die in childbirth if she leaves. A lot of the physicians actually had their families in southern Turkey, and they would go back and forth. Now many of the routes to southern Turkey are cut off, and the city is close to being besieged. The physicians also told us how they tried to keep their spirits up. One person said that when the barrel bombs started falling, he and his colleagues would sing. They refused to be kept away.

"Using medical and scientific evidence to advance the cause of human rights"

Is there a trend of medical care moving away from hospitals to less centralized locations?

Heisler: Definitely. They're hiding. They can't move the hospitals. They considered that, but it's very easy to find out where they've been moved to. When possible, they're moving operations to the basement. Some hospitals leave the top floors empty, so they can absorb the bombs. They're trying to do things like put sandbags around the facility and keep the lights off. And as you say, they're working increasingly in mobile units, teams of doctors, nurses, and technicians providing medical care to civilians outside of medical facilities. That's very difficult. They don't have the kinds of equipment and facilities for many of the surgeries people need, but they're doing what they can.

What can the international community do to assist medical professionals in conflict areas?

Heisler: The UN Security Council has passed resolutions specific to Syria calling for an end to attacks on medical facilities and civilian areas. The key thing is to enforce these resolutions. When Syria started to use chemical warfare against civilians, the international community pushed back and was largely successful. We need to take a similar approach to these violations and make it clear that they are absolutely unacceptable.

Could you tell us a little more about Physicians for Human Rights? How did you, a diabetes expert in Michigan, become involved in a human rights investigation in Syria?

Heisler: Physicians for Human Rights sponsored a class at Harvard on health and human rights when I was a medical student there. A lot of us took it and were inspired. That's when I first wanted to become involved, and I was able to contribute even more when I developed research skills. Physicians bring a lot of skills to this kind of work. Not just the ability to do physical examinations and psychological evaluations, but for those of us who are researchers, also survey methods and statistical skills. I was able to use my experience in academic medicine do analyses and rigorous research for Physicians for Human Rights. That's their mission in the human rights world. Whether it's forensic documentation, pathologists who are experts, epidemiological techniques, they're using medical and scientific evidence to advance the cause of human rights. So for me, my work with diabetes and work for Physicians for Human Rights isn't that different. It's all using research for advancements in human rights and social justice.

This interview was edited for length. Read the full version on ResearchGate News.