"Ted Nugent is a working hard, playing hard, all-American, ass-kicking, son of a bitch, who exudes and defines the soulfulness of American rhythm and blues and rock 'n' roll -- and a pretty damn good bow hunter too." -- Ted Nugent

He may be known as the "Motor City Madman," but when Ted Nugent called me up a few months back as I sat in my hotel room in New Orleans, the way that he spoke reminded me of a book that I once read called, Zen In The Art Of Archery, by Eugen Herrigel. Although the book is one man's quest to understand Zen Buddhism taught through the learning of archery, I found that you could substitute any form of art in place of the word "archery" and it would apply. In the book there is a passage that reads:

... the right frame of mind for the artist is only reached when the preparing and creating, the technical and the artistic, the material and the spiritual, the project and the object, flow together without a break.

Although my interviews primarily are guitar-related, in the case of Ted, I not only wanted to discuss his fascination with the Gibson Byrdland guitar and the musical delivery of B.B. King, but also how important practice and discipline is, regardless of whether you are a musician or a hunter.

Who gave you the nickname Uncle Ted?

TN: You know, I'm such a gregarious, friendly chap. People have approached me all throughout my life, back even before The Amboy Dukes, because, and it's important for your research, the guitar connected me with people. People feel comfortable around me, and they started throwing nicknames at me in a cute, friendly, adventurous upbeat way. And Uncle Ted kind of stuck. I was first called Uncle Ted, geez, over twenty-five or thirty years ago. I just think it was a statement of friendliness. They felt connected to my music, and I suppose, we could also delve a little bit further into the philosophy behind it, and I suspect that it could be accurate, and that is, everybody's got a crazy uncle, and maybe I'm the universal crazy uncle because I'm having so much fun clean and sober that I must be crazy.

Uncle Ted: Which came first, the guitar or the gun? And how old were you?

T.N: Well, you got to realize, Jason, that I was born in a very magic time. I don't think there is a more magic time a guy could hope to be born, for many different reasons. Certainly music is an important moment in time in 1948. Les Paul had just invented the damn electric guitar, basically. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley were already perfecting it. So musically, it was a confluence of some of the most powerful influences that music overall could have, particularly with the guitar. And, combined with the fact that it was post-World War II, where this positive energy and spirit in America, I also believe was unprecedented, in that everyone knew that America "the good" just defeated the Japanese and Nazi evil. So, there was such a joyous attitude and spirit in America at that time, which is why I think that Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley and Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis had such an outrageous, high energy, positive spirit to their music, maximized by the intensity and tonal delivery of the guitar.

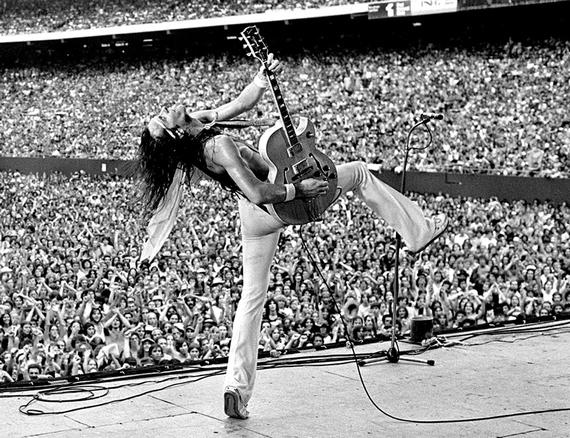

Here we are in 2015, and I'm commenting on guitar tones from seventy years ago that everybody today is still aspiring to get those seventy-year-old guitar tones because they really haven't been beaten. Here we are seventy years later and we have Joe Bonamassa, and myself, and I believe Joe Perry and Brad Whitford, and certainly Derek St. Holmes, and so many guitarists today. I see this Eric Clapton guitar festival that he puts on, and I see guys like Jeff Beck and John Mayer and so many other guitarists that even today, we still nail that original, crisp, bright, rich guitar tone that has never gone away. Only a year ago, Joe Bonamassa played Red Rocks in Colorado and paid tribute to Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf and you just can't get a better guitar tone than that. I had the greatest tour of my life in 2014 called "Shut Up and Jam", and just last week at the Waco, Texas Hippodrome I performed a little history lesson solo with my guitar, and I'm telling you, I had more fun on stage last week than I've ever had, just delving into the history of my guitar influences and tone and god, you should have been there, Jason, then you and I wouldn't have even had to talk because you would have seen my journey where only the dexterity and the capabilities musicianship-wise have really progressed because the guts and the attitude and spirit of my guitar playing has not changed from the ten-year-old Ted from the Detroit garage with my first guitar and amp.

Articulate for me how you feel when you strap on a guitar and play, vs. when you pull the bow back and shoot and arrow.

T.N: Well, I did both today. I do both every day. I shot probably a hundred arrows today and played guitar for about a half an hour. There really is a parallel, while at the same time, being totally opposite in some of the individual manifestations. For example, when pulling back a bow and arrow, you have to be the ultimate reasoning predator, the ultimate conscienscious, stealthy, silent, invisible predator. While with the guitar, it's anything but silent and quiet and stealthy, even though the approach of the guitar neck and the notes that I seek and that I stumble upon it's also very stealth oriented. So there are a lot of parallels but they appear totally different on the surface. While in my heart and in my psyche, both endeavors are about "aim small, miss small." You got to be the flight of the arrow and you've got to be the spirit of your guitar. And that's why this morning, I came up with a couple guitar patterns that are right in line with the "Stranglehold"s and the "Cat Scratch Fever"s and the "Wango Tango"s. That raw drive is alive and well in my gut and in my hands. It's important to note, that the first guitar note ever in the history of human kind, came from a guy with a bow and arrow. The twang of that bow was the first guitar note. And the first drumbeat was that same Aboriginal caveman who used that bow to either defend himself and kill the enemy, kill food, or just pursue the mystical flight of the arrow. The skin of the animal that he killed to feed, clothe and shelter his family and tribe -- that thump on that stretched skin was the first drum beat. And I still have both feet in that primal scream, Aboriginal camp because I still kill my food and make clothes by using my bow and arrow and then I celebrate with music from my six-string weapon of mass construction.

Whether it is a sport or a musical instrument, how important is practice and discipline?

T.N: Essential. Practice and discipline are essential no matter what your dreams may be. Whether it's basketball, welding, carpentry, metaphysical technology, or making killer music. It's all about miles on the guitar neck. It's all about miles behind the wheels if you're planning to be a professional race car driver. It's all about miles with the saw and hammer if you're going to be a great wood smith and carpenter. So, practice and discipline are the two primary battle cries for quality of life.

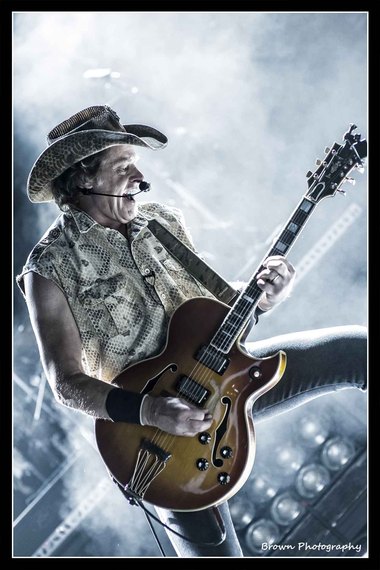

Although the Gibson Byrdland guitar was named after jazz guitar players Billy Byrd and Hank Garland, it's really you who became the brand ambassador for that instrument. When did you fall for the Gibson Byrdland?

T.N: Well, I've said this story many times, and I hope you get it right, Jason. When I first saw Jimmy McCarty with Billy Lee and the Riviera's at the Walt Lake Casino in 1960 or 1961, he was playing a Gibson Byrdland through a Fender Twin Reverb amp and I was only 10, 11 or 12 years old when I heard the rich, thick, tone and the edgy almost feedback. He wouldn't let it feedback, but you know it wanted to because of the hollow-body and spruce arch-top. Well, Jimmy McCarty and Billy Lee and the Riviera's eventually changed their name to Mitch Rider and the Detroit Wheels. That was the first time that I had ever seen a Byrdland, much less heard one played with such power and such fire. And so it was a combination of Jimmy McCarty's style, which is a full-stroke, full-bore playing of all those strings and a lot of counter rhythms and pedal toned approaches to those chordal patterns, and then of course when he whipped into a lead, and put it on that bridge pickup, it had such a bite to it, such a resonance to it, that I was mesmerized by it. It became my life's goal to become one with the Gibson Byrdland. What you hear in my music is a direct representation of the influence that Jimmy had on me.

There have been bands and musicians that have complained in the past that they are tired of just going out on tour to play their old songs. You've done more than 6,000 concerts. Do you ever get tired of playing some of your hits?

T.N: I really don't, because I was smart enough, this goes back to the discipline factor in my life, because I love to hunt, and I love the great outdoors, I consider my September, October, November, December and January months sacred, off-limits time. I play my guitar every day, but I will not tour during that time of year because that's when I hunt. And it cleanses my soul and it charges my batteries. I'm sitting in a beautiful log cabin right now talking to you, Jason, in a big forest in Michigan on a beautiful lake with every imaginable songbird out my window and cranes and I had twenty deer in the yard and I have two Labradors at my feet and my stunningly dangerous wife is doing Zumba upstairs to some god-awful rap music. It's my escape from the music that keeps me bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and craving it.

I understand why musicians do get tired of playing the same old songs; it's because they don't have something that truly distances them from the music and that's what sitting in a tree stand for a thousand hours a year. When you're in a tree stand, you must be invisible and silent and cocked, blocked and ready to rock -- and you got to be able to identify every song bird, and every nuance, and every cackle and every water fowl, and you need to know the difference between a squirrel rustling leaves and a deer coming at you. It so heightens your level of awareness that when you have done that for three, four, five or six months like I do, I can't fucking wait to plug in my Byrdland and rip peoples' heads clean off. It really cleans me out of the sonic bombast and makes me crave it.

Do you have any guitar-related stories that others would find particularly interesting?

T.N: Well, yeah, I've got a lot of heartbreak. I didn't grasp the dynamic of collectability for many years and I got rid of a bunch of guitars that I kick myself in the ass every day for getting rid of. I had a custom Telecaster from 1960 that was just a phenomenal instrument and I just traded it in. My first Fender Duo Sonic from 1959 -- I traded that in on an Epiphone Casino that I traded in on a Gibson Byrdland -- I wish I would have kept all those guitars. Then I had a custom three-pickup white Byrdland that the custom shop in Kalamazoo made for me and it played so badly because they were starting to lose touch in the '70s with their craftsmanship levels, that I just gave that fucking Byrdland away to a German radio contest. I mean, how stupid can I be? I could sit here and cry for you if I let it get to me. My second and third Byrdlands burnt down in a Winnebago fire on the highways of Florida in 1969 or '70. So I got a lot of heartbreak.

If someone didn't know who Ted Nugent was, how would you describe yourself in one sentence?

T.N: Ted Nugent is a working-hard, playing hard, all-American, ass-kicking, son of a bitch, who exudes and defines the soulfulness of American rhythm and blues and rock n' roll -- and a pretty damn good bow hunter too.

Is there anything in your career as a musician that you wish you had done differently?

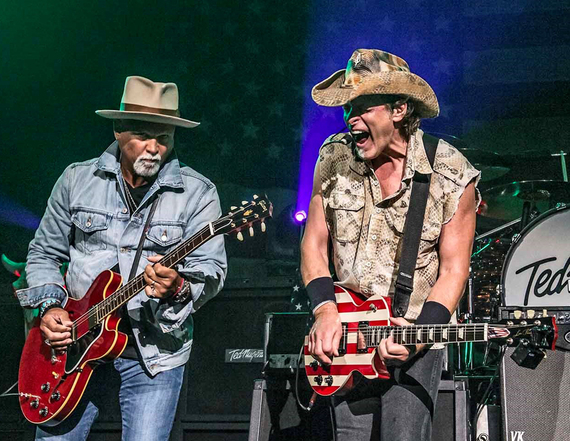

T.N: You know, I don't think that way. I think God has blessed me just by surrounding me with such unbelievably gifted virtuosos all my life. From the Royal Highboys in Detroit in the '50s, The Lords in the '60s, The Amboy Dukes in the '60s and '70s, and the Ted Nugent bands and the musicians that I've been surrounded with Jason, dear God in heaven. I wouldn't have changed anything. I wish I could have saved the lives of some of the guys who went into drugs and alcohol. I did everything I could besides beating them up. But I wasn't in charge of their decisions -- they were in charge of them. Even my mom and dad, who were alcoholics, I couldn't beat them up, but I could pray for them and beg for them to stop; but people have to make those decisions themselves.

What guitar players do you respect the most? Who passes the Ted Nugent test?

T.N: Good grief, there are so many, Jason. Right now, I am rather mesmerized by Joe Bonamassa. I don't think you can do more than what Joe does. There are others like Stevie Ray Vaughan who was also a ten who played differently. Rick Derringer is a ten. Derek St. Holmes is a ten. I admire everyone from Rick Nielsen from Cheap Trick to Joe Perry and Brad Whitford of Aerosmith; Ronnie Montrose was a dear friend, and even guys like Sammy Hagar is a killer guitar player. I've been friends with many great guitar players.

Did you ever have an idea or a defined goal of what "success" would be like as a musician?

T.N: You know, I never thought about it. I've been so obsessed with delivering the music to my ears that I crave that the ten-year-old Ted trying to replicate Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry and Dick Dale and the Deltones and The Ventures and eventually Keith Richards and Brian Jones and The Who and The Kinks and The Yardbirds. I mean, it was such a drive to make the music that the first time that my guitar made sense to me, when my fingers actually delivered something representing what Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry were doing, that was success. And I hadn't even been paid yet.

What's the best bit of advice that you ever received from a fellow musician that you pass on to other musicians to inspire them?

T.N: No musician ever verbalized any direction to me. But when I jammed with B.B. King in 1968, just his musical delivery was the advice that I translated, and I believe accurately and embraced, to make every note count. To say something -- to let your guitar sing. To deliver a guitar solo or guitar pattern that will stay with you. I was only nineteen when I recorded Journey to the Center of the Mind, but you can sing my guitar solos. Nobody ever told me that, but by paying attention, that day, right there in the sweat zone of B.B. King, good lord did that drive it home for me.

For more information and news about Ted Nugent, his music, and causes, visit: tednugent.com