By World Bank economists Otaviano Canuto, Cornelius Fleischhaker and Philip Schellekens

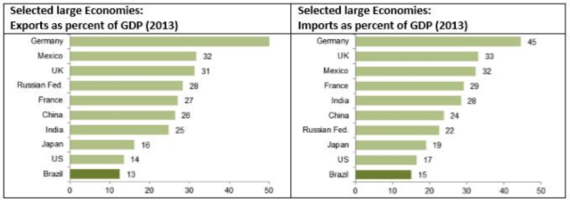

Brazil's is an unusually closed economy as measured by trade penetration, with exports plus imports equal to just 27.6 percent of GDP in 2013. Brazil's large size is often used to explain its relative lack of openness. But this argument does not stand up to scrutiny: Among the six countries with larger economies than Brazil's, the average trade-to-GDP ratio is 55 percent. Given the size of its economy, we would expect Brazil's trade to be equal to 85 percent of GDP, three times its actual size.

Controlling for other dimensions of country size (surface area and population) and structural features often associated with trade openness (urbanization, manufacturing share in GDP) still cannot adequately explain Brazil's lack of openness.

Source: World Bank WDI database

Lack of trade dynamism at the company level

Brazil's lack of openness becomes even more apparent if we look at the number and characteristics of exporting companies. Very few Brazilian companies export. Indeed, the absolute number of exporters in Brazil -- fewer than 20,000 -- is roughly the same as that of Norway, a country of just over 5 million people compared with Brazil's 200 million. This means that, while in Norway there is one exporting company for about every 250 Norwegians, the ratio in Brazil is one for every 10,000 Brazilians.

Of course, Norway and Brazil are vastly different countries. But looking at a larger set of countries, we observe that Brazil is indeed an outlier. Its number of exporters relative to the population is low even when controlling for GDP per capita.

A very small number of companies are responsible for the overwhelming share of Brazilian exports. The top 1 percent of exporters generate 59 percent of total exports, while the top 25 percent account for 98 percent of export revenues. Brazilian exporters also lack dynamism. Brazil has a very low entry rate, very few companies become new exporters, and established exporters have a very high survival rate.

Why do so few companies export?

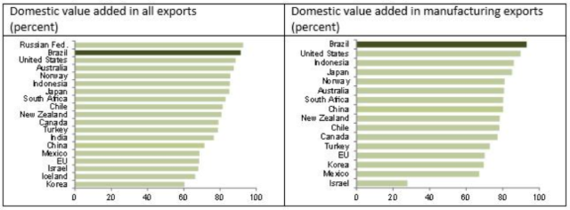

Brazil's extraordinary lack of openness and its small number of exporters are closely related to the fact that Brazilian companies are poorly integrated into transnational value chains. This can be observed in the very high share of domestic value added in Brazilian exports, which implies that such exports incorporate few components and intermediate goods imported from other countries.

The high level of domestic value added is not accounted for solely by Brazil's commodity exports, which have a very high degree of domestic value. Even in Brazil's manufacturing exports (about a quarter of total exports) domestic value added is still extremely high, at 93 percent. Indeed, it is the highest among all economies for which such data are available.

This high level of domestic value added shows that the global fragmentation of production processes along cross-border value chains, a very important part of the second wave of globalization, has largely bypassed Brazil. The factors behind this are multiple. They include precarious logistics and high transaction costs related to international trade, as well as deliberate policy decisions to favor local content over international integration.

Source: World Bank 2014

Over the past decade, Brazilian companies have also faced serious challenges to competitiveness, such as exchange rate appreciation and defensive trade policies. The result is that only the largest and most efficient companies enjoying significant economies of scale are able to overcome barriers to export.

How could opening up support Brazil's growth agenda?

Opening up and integrating more deeply into global value chains would result in the closure of uncompetitive production chain segments and their replacement with imports. The surviving businesses would be more competitive thanks to their access to imported inputs, allowing them to create products of lower cost and higher quality. Furthermore, in dynamic terms, integration into global value chains would allow scarce domestic resources such as skilled labor to be reallocated to the most productive companies and activities, increasing overall productivity.

As the potential productivity gains from participation in global production networks increase, so does the opportunity cost of Brazil's failure to open its economy. The alternative to openness -- vertically integrated supply chains behind protectionist barriers -- is likely to be futile in the long term. Despite rising trade barriers, Mercosur's coefficient of imports from China has continued to increase in recent years. Private investors understand this, as they shy away from activities that are viable only under permanent protection.

Given Brazil's current labor shortages, productive activities would be strengthened by the availability of imported intermediate and capital goods. Brazil's immersion in global value chains would allow the country to leverage its comparative advantages which clearly exists in natural resource-associated industries but which could also emerge in specific activities in manufacturing or services, once industries have access to cheaper inputs. Of course, the support of public policy remains essential.

However, such support should be more horizontal in nature, rather than further encouraging the ongoing high density of production chains and perpetuating the extraordinary lack of openness in the Brazilian economy.

Otaviano Canuto is a senior advisor and former vice president at the World Bank; Cornelius Fleischhaker is a junior professional associate at the World Bank; and Philip Schellekens is a senior economist at the World Bank. All opinions expressed here are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

This post is adapted from a version originally published on the Financial Times' beyondbrics.