Part of the China by the Numbers Series

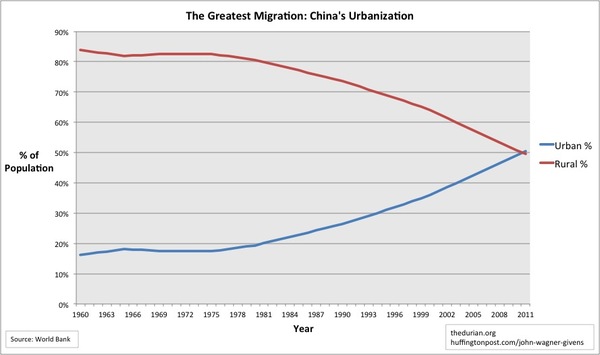

There is no doubting the appeal of stories about average Chinese holding out for more compensation for their homes and farms by resorting to homemade rocket launchers and Kung Fu or nail houses that continue to stand in the middle of streets or giant pits. Yet, they are not representative of the epic human tale of China's urbanization. The larger story, which can really only be told through numbers, is about how "China's urban population has increased from 180 million people in 1978 to 690 [million] now" and since rural birth rates consistently outpace urban ones, it is specifically a tale of rural to urban migration.

This is a staggering thought: "Roughly one out of every 25 people in the world today is a resident of a Chinese city who arrived, or was born, since the current round of economic reforms began in 1978." This is a staggering figure, even if some of this has been rural dwellers who have simply had giant cities spring up around them. For example, there were 310,000 people living in the rural Shenzhen prefecture, before it grew to a city of over 10 million and became part of the 65 million-strong urban mega-region that stretches from Guangdong to Hong Kong. Mostly though, China's urbanization is the result of millions of, often young, rural inhabitants leaving their farms and families behind and moving to the cities for better economic opportunities.

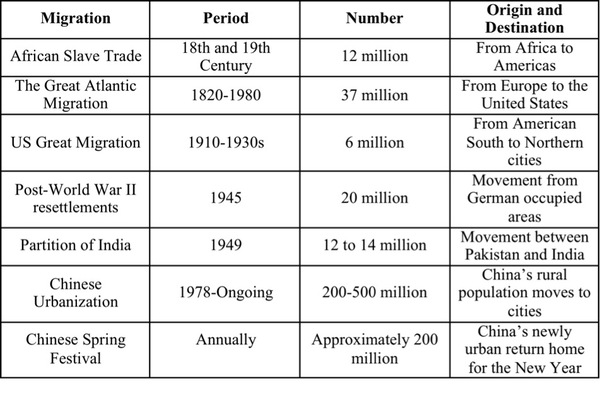

They do not forget their families, however, and often make herculean efforts to return home for the Lunar New Year, which for many workers is the only holiday long enough to allow them to travel the long distances to their home villages. During the peak holiday period 200-million-odd urban migrants attempt to travel from large coastal cities to the inland countryside and back. This number may eventually decline as migrants gradually lose ties with their home villages, but for the foreseeable future this is the largest migration in human history, every single year.

Qualitatively, China's urbanization is not that different than that which has occurred elsewhere. The movement of surplus labor from the countryside to cities where there are more profitable outlets for it and the remittances that return to the countryside are an integral part of economic development. What makes China's migration so mind-blowing, however, is its scale and speed. The scale is largely a product of China's size and its delayed development. If the less populous China of the 19th century had urbanized when Europe did, we would have been talking about tens of millions, rather than hundreds of millions of migrants.

The speed of China's migration flow is also intimately tied in with its politics. In particular, a system of evaluating local officials that rewards local Chinese officials for development above all else has helped produce the breakneck economic growth that drives China's urbanization. Even where the economic incentive is relatively weak, officials may be driven to push urbanization. As Andrew MacDonald and I argue in a forthcoming paper (download it for free), the elimination of China's agricultural tax has left officials in rural areas with gaping local budget deficits and many have turned to the seizure, sale, and development of rural land as a response. The dramatic results can be seen in a 2005 survey which found that government land expropriation (generally the first step in urbanization) had grown by a factor of fifteen in a decade.

The impacts of China's urbanization are profound and widespread, from hastening the demise of China's dialects, to creating a need for natural resources that reaches out to Africa, Australia, and Latin America. Before assessing the impact, however, it is worth taking a step back to appreciate that the sheer scale and speed of this event make it one of the most important in recorded history.

(Special thanks to Andrew MacDonald for the genesis of much of this post.)