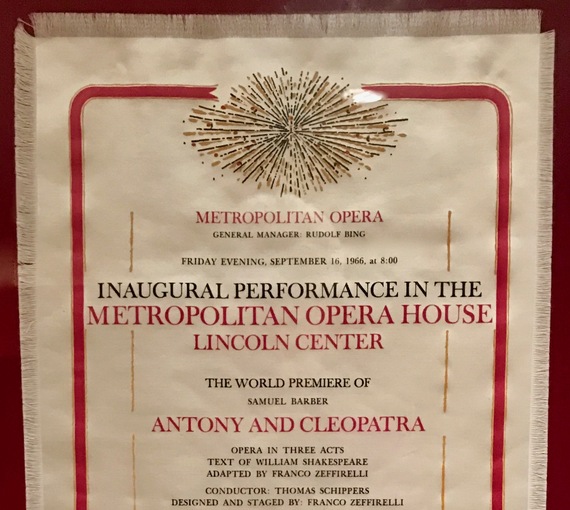

That's what it was like -- and perhaps still is: a delicious, venomous trashing of a serious and magnificent achievement that was not perfect by any means but was also profoundly memorable -- so much so that just hearing an archival recording of that opening fanfare 50 years later brings it all back to me. (Leontyne Price attended the revised version of the score at Juilliard ten years after the premiere, and famously said when she heard those first notes, "Honey, I broke out in a cold sweat.")

The audience, in retrospect, really enjoyed the opera. The critics, however, hated it. Everyone and everything was sent into the trash in a collective expression of mid-century revulsion and umbrage. How dare anyone write music that extended tradition, rather than something completely new and avant-garde? Poor Aaron Copland had tried the "completely new" route a few years earlier at the opening of Philharmonic Hall with his Connotations for Orchestra, which the audience positively hated, even if the critics were equally loath to give him points for his musical volte face into serialism. (First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy was famously heard greeting him afterward and at a loss for words, saying only, "Oh Mr. Copland! Oh Mr. Copland!") Aaron had tried to be "with the boys" by writing a 12-tone piece, whereas Sam had more or less stuck to his artistic guns and wrote a grand opera for the 20th century. Both works have been unceremoniously dumped. Barber became so depressed that his output shriveled, as did Copland's. Antony and Cleopatra was deemed to be a "giant fiasco," in the words of The New York Times' Peter G. Davis, "one of the great operatic disasters of all time." It should also be pointed out that other operatic disasters include the world premieres of Carmen, La Traviata, and Madama Butterfly.

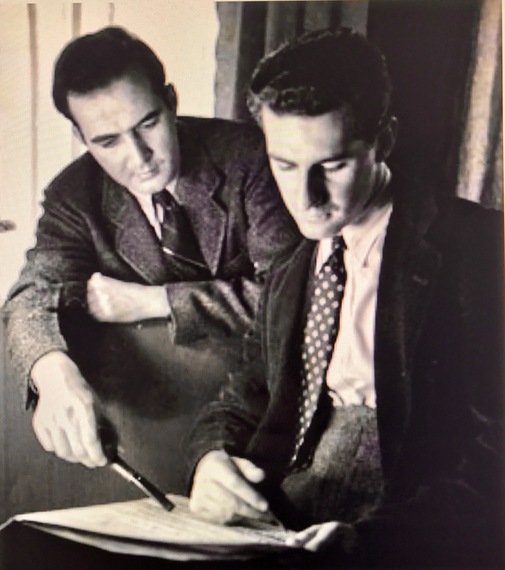

Sam Barber was so profoundly hurt that it inspired his former domestic partner, Gian Carlo Menotti, to come to his rescue. Sam and Gian Carlo never stopped loving each other even as they stopped being each other's lovers. When I first met Barber, Menotti introduced us at Spoleto in 1974 where I was conducting the European premiere of Menotti's one-act anti-war opera, Tamu-Tamu, and their mutual warmth and comfort were palpable and radiant. Schippers was conducting Luchino Visconti's magnificent production of Manon Lescaut, and Roman Polanski was directing an ill-conceived production of Alban Berg's Lulu in Italian. Jerome Robbins was there too, as was a young designer-writer whom Gian Carlo had discovered called "Bawbweelsohn" (Robert Wilson!). Sam was visiting Spoleto and we spent a bit of time together. Gian Carlo was always trawling for some bit of juicy gossip. "How are you getting on with the other conductors?" he asked me with a raised eyebrow.

It made a certain sense that Menotti, the composer of sixteen operas (as of that date), and the librettist for Sam's other Metropolitan Opera commission, Vanessa, would take over the score of Antony and Cleopatra and reshape it with his beloved Sam for performances in New York at the Juilliard School in 1976, and subsequently at the American Spoleto in Charleston. This time, Gian Carlo would also direct the proceedings.

Menotti hated the dance music ("Very camp") and removed it. He also felt that the score needed a love duet, even though Shakespeare did not provide anything like that in his play. Thus, in Scene 4 of Act Two, just before the Battle of Actium, there is a short duet of approximately fifty bars of music that makes use of words by the English dramatists Beaumont and Fletcher ("Oh take! Take those lips away"). The chorus is omnipresent in the revised version, but remains unstaged and upstage, focusing the drama down front -- and eliminating a lot of rehearsal time. Melodramatic bursts occasionally replaced Barber's more controlled drama, as when Cleopatra screams at the sight of Antony's body being hoisted into the monument where she will soon join him in death, and "kisses him wildly" in seven new bars of orchestral passion. Caesar's part has been diminished, and with the removal of the part of the court eunuch, Mardian, Menotti also scratched one of the clearly-perceived phrases from the 1966 opening night that made us laugh inappropriately: hearing Miss Price's Cleopatra ask character tenor Andrea Velis, in perfectly enunciated Mississippi-English, "Dost thou have desires?"

The cuts and emendations of the revised 1976 edition are interesting and authentic, of course, but also remove much of the grandeur and internal balance of what was clearly a grand opera. It is the only version that is currently available for performance, and Menotti, who died in 2007 at the age of 95, steadfastly defended it in terms that made it clear that he was protecting Sam. It was Sam Barber, after all, who had protected him in 1928 when, as a frightened teenager enrolling at Philadelphia's Curtis Institute of Music, he could not speak a word of English. "I heard a kind voice behind me say, 'Vous êtes Italien?' and it was Sam," Gian Carlo had told me. "He took care of me."

The last time Sam and Gian Carlo visited the Met -- shortly before Barber's death in 1981 -- the two tried to go backstage after the performance, but did not have a pass, nor did they have their names on any official list. They were not granted entry, even though Gian Carlo tried to explain to the guard that his companion had composed the opera that opened the house. Menotti recounted this story with great bitterness when we last saw each other in 1999.

Antony and Cleopatra is Shakespeare's celebration history's most famous love affair. Historically, it marked the end of an era. Cleopatra was the last pharaoh after all, and with the death of Antony in 31 B.C., Octavius Caesar became Rome's first emperor. Sam Barber's original opera was meant to represent, as The New York Times critic Peter G. Davis said, "the sunset tragedy of two mature lovers trapped and destroyed by international politics." It may also have signaled the end of another era: America's classical foothold in world music. The World War II School from Europe, led by Pierre Boulez, had told us we Americans had no real composers ("not even a Henze") and our leaders accepted that judgment. The American sound that Copland, Barber, Blitzstein, Bernstein, Hanson, and others had created was passé and only a few composers continued to write operas in that hugely successful American voice (Floyd, Ward, Beeson, Argento) -- but we have turned our backs on all of them. Its post-mortem is the 1976 revised Antony and Cleopatra, which is also something of a final love letter from one man to another, Sam and Gian Carlo, both of whom had seen their reputations all but disappear during their lifetimes.

Barber did not make his text easy to sing. His musical evocation of Roman and Egyptian music, however, is great and persuasive. Unlike Alex North's masterpiece for the 1961 epic film Cleopatra that tells the same story in its second part, Barber makes a different case for how we can imagine a past whose music we do not and cannot actually recreate.

Verdi made up Egyptian music for Aïda by using exotic scales, flutes and harps (as seen in ancient Egyptian painting), and historically inaccurate brass instruments to represent the repressive power of the Egyptian Empire. North, who, in addition to being thoroughly trained at Curtis Institute, Juilliard, and the Moscow Conservatory, was also a jazz musician and a student of what we used to call "ethnomusicology." Thus, his Egyptian music (like Verdi's a century before) uses flutes and harp-like instruments, but expands the palette to include bass flutes, tuned gongs and the clattering harpsichord, frequently built over jazz grooves and riffs to indicate the African nature of Egypt. Barber finds his own way by remaining true to the complex idiom of mid-century counterpoint, complex and dense harmonies and declamations, and the occasional big tune -- the very thing that turned the serious music critics of the time into serious haters of his music -- even as they accepted the phantasmagorical Hochkitsch of Messiaen, Boulez's teacher. Ironically, much of today's "modern music" owes far more to Samuel Barber than to Anton Webern (1883-1945) who in 1966 was the godfather of all contemporary music -- both American and European.

Music is invisible and there is no way to reassess it without performing it. We are constantly coming to new conclusions about art whenever a museum collects and presents that art, but we cannot hang an opera on a wall. We have to perform it for you to hear it. Those of us fortunate enough to have been at the opening of the Met and the premiere of Antony and Cleopatra have lived to tell of it and would encourage the rest of the world who still care about opera to share in that reassessment. There were eight performances of it at the new Met in 1966. Thirty thousand people attended Antony and Cleopatra -- and it was as successful as any new opera ever presented in the second half of the twentieth century. Its critical drubbing in mid-twentieth century America did what could not be done in the 19th century to Carmen and La Traviata: it stopped it and its composer. Much the same thing happened to Menotti, who went from Pulitzers to pulverized, and retreated to Scotland "where I did not have to read The New York Times every morning" -- though he continued to write operas.

But really, Antony and Cleopatra is a good opera -- maybe a great one. If we cannot find room for a major work by a major, internationally celebrated composer, how can we expect opera to survive? Feeding the repertory is the only way forward and surely it is not merely a question of commissioning new works. There must be room for Barber and Menotti on our stages because we owe it to our composers and to ourselves. Fifty years is the crucial point for a musical work. It has already gone from new to old and now awaits reassessment. Will it be rediscovered? Will it be a classic? Will we simply ignore it and await some champion who might use another anniversary, divisible by ten, to justify dusting it off and presenting it "for your consideration" as the Motion Picture Academy likes to put it at Oscar time?

Classical music continues to present its core opera repertory -- presenting it in new and frequently controversial productions -- and then suddenly jump over fifty years or more to commission and present new works, skipping the mid-century. Broadway, Hollywood, pop music -- and of course art and design -- have room for this complex and diverse period and are a lot healthier for it.

On September 16, 2016, I sat in the darkened Metropolitan Opera House. I watched an army of brilliant technicians, stage managers and stagehands, custodial staff and carpenters hard at work during an all-day stage-and-orchestra rehearsal of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. Sir Simon Rattle was (understandably) totally unaware that he was leading this rehearsal on the 50th anniversary of the opening of the house. Nothing was said to the orchestra or the artists. It was just another rehearsal.

I listened as Simon coaxed the first two notes of the prelude to Act One out of the cello section. Perhaps he repeated this passage ten times. I felt the multiple geniuses on display that day: Wagner, of course, and Wallace Harrison and his fellow architects and designers who had created the magic proportions of an auditorium that lets music and singing envelope us; Simon, who knew just what he wanted and demanded it with charm and insistence; the orchestra and the cast -- who were moving about and singing as the set was being adjusted and the lighting was still being tried.

An assistant conductor sat behind Rattle in the first row. It reminded me of when I sat behind Leonard Bernstein, taking notes and following along as he rehearsed Carmen with Marilyn Horne in 1972, and I thought about the eleven Fidelio performances I had conducted there in 1976. Harrison made the relationship between the conductor and the stage so completely natural that one never has any idea just how gigantic the space behind us is. (Covent Garden and Scala are both a thousand seats smaller.) It is just the conductor, the orchestra, and a stage that seems close and intimate. In other words, the Met is a miracle of design.

As I sat in the darkened theater, a familiar face came up to me. It was Ken Howard, a photographer I have known since Santa Fe in 1973 when he photographed, and I conducted, a new production of Così fan tutte there. He is now the principal photographer for the Met. When the lights came up during a break he offered to take a photo of me, fifty years after Aunt Rose and I sat upstairs to experience Antony and Cleopatra and the new Met for the first time.

The new house is no longer the new house. It is the Metropolitan Opera House and the old house is simply a glorious memory of my youth. And while we can rejoice in the achievement of the fifty-year-old house -- because it is there to be experienced -- we can also wonder at what music awaits rediscovery. On May 7, 2017, the Met will hold a gala with arias and ensembles from many operas and, for the first time in fifty years, it will perform "excerpts from Antony and Cleopatra." Maybe you will be there and, having heard those excerpts in the hall that first brought it to life, you will want more of it. Perhaps, as Gustav Mahler once said of his own music, its time has come.