Many friends have urged me to visit Zahav restaurant in Philadelphia. Zahav is well-known for its Israeli-themed cuisine, especially its hummus, which is considered by many to be among the best outside of Tel Aviv.

So I put Zahav on my travel to-do list -- who can resist good hummus? -- without understanding what an incredible and transformative culinary experience I would have when I was finally able to visit Zahav last week.

Philadelphia was still digging out of the East Coast's huge snowstorm. A taxi dropped me at -- or rather, dropped me as close as it could get to -- the restaurant. Zahav is set within the grounds of the Society Hill Towers, a 1960s apartment and retail complex. I navigated around four-foot high snowbanks and up a steep icy staircase to reach Zahav's entrance.

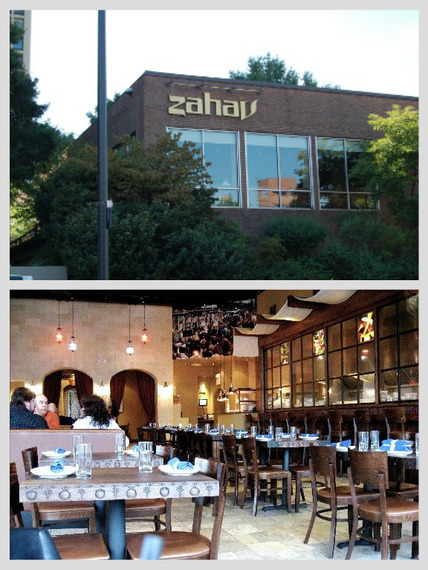

The Society Hill neighborhood is near the city's historic center, and includes the architecturally beautiful Society Hill Synagogue, dating back to the early 1800s. The Tower complex is a typical mid-20th-century bad idea -- an ugly modernist high-rise plaza set brutally down amongst rows of elegant centuries-old town houses. Zahav occupies a bricked and windowed rectangle overhanging the street. From the outside it exudes all the charm of a suburban JCC social hall -- which only makes the experience to come more unexpected.

Inside, the restaurant has been transformed into a cool loft space: lots of leather booths, dimmed pendant lights, and a long wood eating counter with a view of the kitchen. One wall has two inset arches and is covered in Jerusalem limestone. Zahav's name means "gold" in Hebrew. The name is chef Michael Solomov's tribute to the golden city.

Zahav, exterior and interior.

Solomonov himself greets me at the eating counter, where I have taken a stool to watch his team grill fish and kebabs over a line of small barbecues. He's wearing a short-sleeved chef's coat that displays two well-cut biceps inked with tattoos. He has a gentle, boyish face with a dash of Philly pugnaciousness, framed by Israeli-style close-cropped hair (the stage before they shave it off completely).

At age 38, Solomonov has already been named "Best Chef, Mid-Atlantic" by the James Beard Foundation (2011); in 2014, he was declared Eater's National Chef of the Year. With his (aptly named) partner Steven Cook, he formed the restaurant group CookNSolo, which now operates four restaurants in Philadelphia: Zahav; Abe Fisher, which offers American Jewish style small plates; Dizengoff, a hummus-based cafe; and Percy Street BBQ, serving what the name suggests; and Federal Donuts, featuring coffee, donuts and fried chicken (and is something of a local legend). The group will launch a branch of Dizengoff in New York's Chelsea Market in March.

Chef Michael Solomonov. Photo by Steve Legato.

Your assumption when you meet Solomonov is that he must be, obviously, Israeli. Indeed he was was born in G'nei Yehuda, originally a farming community founded by Poles, now a suburb of Tel Aviv. His mother was an American teacher, his father, a Bulgarian immigrant. But his parents returned to the U.S when Michael was still a baby, and he grew up in Pittsburgh. He did not return to Israel until he was 19, where he got a job as a baker and learned Hebrew. And so a career was launched.

But what career, exactly?

Zahav's cuisine is described as "modern Israeli" but that's not quite right. The only truly Israeli thing about it is its creativity and daring.

Like many of the new top chefs in Israel, Solomonov has abandoned the notion of a regional Middle Eastern cuisine -- based on a mash-up of Sephardic and Arab cultures, so beautifully captured by Yotam Ottolenghi in his seminal cookbook, Jerusalem.

Instead, Solomonov -- like the young chefs I met at Mona, Dalida, and Taizu, to name a few -- is exploring and experimenting with a multitude of ethnic influences. Some recipes are based on his own roots (American, Eastern European) while others embrace the hundreds of different ethnic streams that compose modern-day Israel: Yemenite, Moroccan, Ethiopian, Turkish, French, you name it. The result is a startling amalgamation of ingredients and spices that never expected to mingle together, but here they are -- like a joint session of the UN, but getting along much better.

How does this translate into actual dishes?

Solomonov leaves me but instructs the kitchen to barrage me with a selection of the restaurant's top hits. I've already chosen a Har'el Syrah by Clos de Gat -- Zahav has one of the most extensive lists of Israeli wine I've seen outside the Mamilla bar in Jerusalem. The staff ask about any dietary issues and I allow, meekly, that I don't especially like organs -- so of course among the first dishes to arrive is grilled duck hearts. They are walnut-sized, resting inoffensively upon a bed of pear and pine nut salad with a celery tahini sauce (I will quickly gather that the guy is the Ben & Jerry's of tahini -- throughout the evening he will dazzle me with a crazy number of flavors he makes from what is generally regarded as the ketchup of Israel).

I reluctantly -- no BRAVELY -- bite into half a heart (half-heartedly) and am immediately ashamed of my reluctance. Imagine a perfectly plump piece of fois gras with a slightly steaky texture, enhanced by the refreshing, fruity crispness of pear and celery.

More plates arrive: Lamb merguez sausage with pumpkin seed tahini, poached cranberries and pickled squash over Basmati rice, with a side of house pickles. Beets twice roasted with tahini and dill. Coffee-roasted sweet potatoes with Urfa (dried Turkish chili pepper), shallots, mint and a cardamon labneh. And this is all just for starters.

From left, clockwise: Roasted cauliflower; Hummus; Twice-Roasted Beets; Grilled Haloumi. Photos by Jason Varney, Mike Regan, Michael Persico, Felicia D'Ambrosio.

As I'm munching my way through these constantly arriving dishes -- wondering how I'm going to pace myself -- I'm struck by the fact that the majority of them are vegetables. Maybe this is the most Middle-Eastern aspect of the meal: You can be a full-blooded carnivore but when presented with shuk ingenuity -- fresh produce and a few hundred ancient ways of cooking them -- you don't miss meat. You forget entirely about meat. (Not to say there isn't meat on Zahav's menu -- there's lots, and it was to come. Aside from the merquez, I tasted his chicken shashlik [grilled Turkish-style kabob] and a raw yellowtail crudo with celery and cilantro. Yum yum.)

Solomonov is, natch, a shuk junkie. In this recent charming Saveur profile, Solomonov is described going through the food markets of Israel like a four-year-old boy in the superhero aisle of a toy store. There is not a single weird spice or perfectly ripe vegetable that doesn't excite him. As I reap the benefits of his enthusiasms, I start to believe he is the Match.com of cooking. Somehow he is able to figure out an ingredient's essential characteristics -- and then marry it to other ingredients that weren't, say, obvious choices but end up producing successful outcomes.

So those twice-cooked beets with dill AND tahini -- that's the profile of the Polish model who moved to Tel Aviv and ended up happily ever after with a guy named Achmed. In another small plate, wallflower green beans take off their glasses and let down their hair under the influence of smoked paprika and coriander; carrots -- meh, carrots -- suddenly entrance Moroccan-style with cumin and mint; bland pointless haloumi, to me the Velveeta of the Arabic world, comes alive when it's homemade, grilled, and served with a date-walnut jam with pickled onions, apples and dill.

Roasted cauliflower these days is something of a plat du jour so Solomonov rests his perfectly caramelized florets upon a streak of herbed labneh and then dusts them with sundried Aleppo peppers. (Because he can.)

"'Modern Israeli cuisine' is not really an accurate description [of what I do]," Solomonov mused during a short break from the kitchen. "I want people to know Israeli food and say, 'I get this. I get the reference.' But the idea of Israeli food becoming global is a new thing. It's transcending shwarma and hummus. It's about all these different cultures coming together in one place. Global fusion exists organically."

And will grow organically under the genius of Solomonov, who blows up every notion we have of conventional flavors and genres to create an entirely new concept of fusion.

Which is all fine and great, but what about the hummus? Does Zahav's version live up to billing?

It was, in fact, the first dish to arrive -- as if to say, "We know you came here for the hummus so we're getting it out of the way" like a pop star who has to open the concert with her first big hit.

"I sometimes wonder where my career would be without hummus," Solomonov muses in his cookbook, Zahav. "There's something transcendent about the perfect bowl of hummus that tells our guests they're in the right place. I often imagine that somewhere beneath the restaurant is an engine room with two guys shoveling hummus into a giant furnace that keeps the stoves lit and the lights on. Without hummus, Zahav would be a cold, dark shell."

In fact, one of the first things you notice when you enter the restaurant is the glow of a wood-fired oven beside the kitchen. Solomonov is not going to serve you his hummus without homemade pita. A big flap of it arrives on the side, gently scorched on the outside, warm and soft when you tear it apart. The hummus is served Israeli-style: creamy and swirled flat on the plate, with a well of olive oil in the center. The trick is to take a shard of pita and pilot it through the center of the hummus like ... well, a snowplow clearing a street (for a ready analogy). I bit down -- and swooned. The hummus is seasoned with smoked paprika and cumin, conjuring up pita dens in Old Jaffa. The restaurant uses Lebanese olive oil. Later I will curse myself for how greedily I gobbled it down. But in that moment, anti-carb diet and pacing myself be damned.

Zahav's recipe for Twice-Roasted Beets can be found here.

NEXT WEEK: I taste Solomonov's take on American Ashkenazy at Abe Fisher in downtown Philly.

For more content like this, and beautiful artisanal Jewish products, please visit Fig Tree & Vine, the stylish destination for contemporary Jewish living. Follow us on Instagram @figtreevine and Facebook, or subscribe to our newsletter.