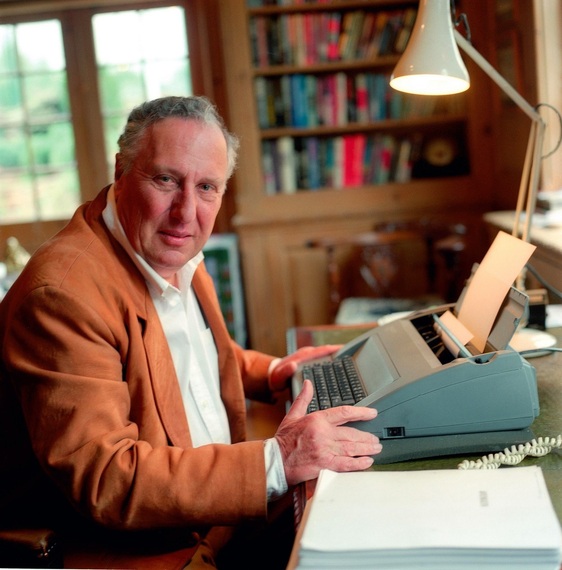

Photo: Gillian Shaw

Frederick Forsyth has written some of the world's most acclaimed and successful suspense novels. Beginning with The Day of the Jackal, and followed by The Odessa File, The Dogs of War, and twelve others, Frederick Forsyth has mesmerized millions of readers and moviegoers with stories about assassinations, conspiracies, civil wars, the drug trade, mercenaries, and international intrigue.

A former Royal Air Force pilot and reporter for Reuters and the BBC, he won the Diamond Dagger Award from Britain's Crime Writers' Association in 2012 for a career of sustained excellence.

The Outsider is his most exciting tale of all--his own. Written in a lucid, conversational style, it tells stories as intriguing as his most thrilling novels.

As described in The Outsider, how did The Day of the Jackal come into being?

I had the best reason in the world for writing it: I was absolutely broke. I'd returned from an African war and was in London, but had no apartment, no car, no job or any prospects of a job, and certainly had no savings. I thought, 'What does one do?' and came up with the most naïve answer: 'You write a novel and make some fast money.'

Well, you don't. (Laughter).

If you make any at all, it's a miracle. And, it is slow. But, I didn't know that. I know now if you want to make money, do anything, but don't write a novel. Anyway, I sat down and wrote the only story I could really think of, which was something I'd seen personally seven years earlier back working for Reuters Agency in Paris in 1962-1963. It was the repeated attempts by the OAS to assassinate Charles de Gaulle. I saw them try and fail, over and over again.

I concluded they would fail unless they came up with an outsider unknown to the French authorities--someone with no face, no name, no passport, but with a gun. And that was what I sat down and wrote.

Is it true you wrote the novel in thirty-five days?

Right. But I had nothing else to do. (Laughter). I was lounging on a friend's couch. He went off to work mornings; I took my typewriter and five-hundred sheets of paper to the kitchen table; rolled the first sheet in; and began to type off the top of my head. I had virtually no notes. It was all there in my memory, along with some imagination. I invented things that didn't happen, but decided to write what would have happened. I was writing about twelve pages a day, and thirty five days later, there was the novel.

Even though I knew de Gaulle was never assassinated, I kept turning the pages to find out what would happen.

I tried to persuade the first four publishers who rejected it that it wasn't about whether de Gaulle lived or died. It was about how close to happening it would be in the man-on-man duel between the Jackal and the French detective on his trail.

The Outsider describes your research for The Odessa File and how the movie version led to the capture of a Nazi War criminal. Will you share that with us?

The inspiration behind using this man, Eduard Roschmann, the 'Butcher of Riga,' was Simon Wiesenthal, himself. I visited him in Vienna and told him I was trying to write a story that mirrors the capture of Adolph Eichmann in Argentina by the Israeli Secret Service. But in the prospective novel, he would be discovered inside Germany, using false papers. Wiesenthal asked me what kind of character I was thinking about and I said, 'Maybe a concentration camp commandant. A man of singular cruelty. I'll have to invent one.' He waved toward a stacked shelf and said, 'Why invent one. I have twelve right there. Which one would you like?' So I settled on Eduard Roschmann, the "Butcher of Riga." The book was published and the movie was made.

Then, somewhere in a little, flea-bitten cinema south of Buenos Aires, a man was watching the movie and said, 'I know that man. He lives down the street from me.'

He went to the police. It was during one of those brief windows of democracy in Argentina--between generals--and the government arrested Roschmann.

Some magistrate, with right-wing leanings, gave him bail, and Roschmann decided to flee to Paraguay, a safe haven for Nazis back then. He was actually on a ferry going across the Paraguay River when he had a massive heart attack and died. The Paraguayans didn't want him, but the ferryman said, 'He already paid his fare.' (Laughter). So the body remained there, and the ferry went back and forth with the body on the foredeck--until he began to stink.

Eventually, they got him off on the Paraguayan side, where Viennese police officers were waiting. They identified him with photographs and fingerprints. They also knew Roschmann had two missing toes from frostbite. The police knew that from reading The Odessa File. So, he's buried in a gravel bank somewhere on the northern side of the Paraguay River.

Wanting to be a pilot more than anything else, you were an RAF fighter pilot at nineteen. The Outsider details how your writing career almost didn't happen. How did you make the transition from reporting to writing fiction?

I was a foreign correspondent and then worked for the BBC. I had a serious disagreement with the BBC about how the Nigerian-Biafra War should be reported. They said it shouldn't be reported at all. I said, 'You can't ignore a war.' They said they could avoid covering a war.

I did not become a journalist to participate in managed news for any government department, so I walked.

I went back into the forest for two years, and covered the war. Eventually, the good guys were crushed. I got out on the third to last plane. I returned to London and asked myself the question, 'What the hell should I do now?' And that's when The Day of the Jackal got written.

After that, the editor wanted to sign me up for two more novels. It was a real body blow. I thought I would only do one novel. I didn't know if The Jackal would even sell; nor did the editor. In fact, they only printed five-thousand copies. The last count was around ten-million, but never mind. I didn't see myself as having the capacity to tell stories. I asked myself, 'What the hell do I know about?'

Well, I know about Germany. I'd heard about this bizarre pro-Nazi self-help organization called ODESSA. I also knew about West Africa, since I'd been there with the mercenaries. I told the editor and he said, 'Okay, Nazis first; mercenaries second, and I want the first one by the end of the year.' So, they became The Odessa File and The Dogs of War.

The Outsider details some of your near-death experiences. Tell us about them.

I'm not a danger freak. I never deliberately walked into perilous situations because I wanted to experience the danger. I was born with an extra-large bundle of curiosity. There are instances in the book where, looking back, they're funny; but at the time, they were scary.

I'm seventy-seven and still around. I took the risks and I'm still here.

What was the scariest incident you recall?

When I was coming out of East Germany one night. I had a packet of documents I was to deliver to British foreign intelligence. I was in a deserted area, about to store it under the car's battery, when suddenly the whole area was illuminated in a wash of white light. I recognized the car: it was the People's Police of East Germany. I said to myself, 'I think I am done for.' But, by the grace of the big gentleman in the sky, it didn't happen. The reason they swept into the area was the fact that one of them wanted to relieve himself in the undergrowth. I was nearly discovered but was saved by a bursting bladder. (Laughter).

What made you choose the title for the memoir, The Outsider?

I really never wanted to be part of the herd, or run with the mass. If you join in, you lose your autonomy. You have to abide by other people's rules. I always preferred to stay outside the mainstream and perch like a bird on a rail and watch the game. The air force was a meritocracy. You didn't get your wings by succumbing to office politics.

Reuters was also a meritocracy.

The BBC was governed by politics and coteries with everyone vying for promotion.

Do you have a favorite of all your novels?

I have to remain grateful to The Jackal. It gave me my break. Had it been turned down any more times, I'd have put it in a drawer and gone back to journalism. It set me on a new road. That apart, I think possibly, The Fist of God might be my favorite. It's the story of the First Iraq War. I began to ferret out things that were true, but we hadn't been told.

What's the most important lesson you've learned about writing?

Keep it simple.

We all write in different ways. Some writers use flowery language and have beautiful prose. I write like a journalist. There are no frills. Keep it understandable. The guy on the commuter train doesn't have time to admire beautiful Bronte-esque prose. He wants the story. If I were to divide a novel into parts, it would be like this: twenty percent would be characterization, descriptive passages, dialogue, and prose style. Eighty percent would be plot.

I'm basically a storyteller.

Do you have any advice for writers starting out?

It's one of the hardest professions of all. It's probably as difficult as starting out as a young actor. You need a break, and the way to get that break is determined only by perseverance. A beginning writer must keep trying. A new writer will be rebuffed, as are actors in auditions. There will be a drawer full of rejection slips. But those who made it did so by just refusing to take 'No' for an answer. And also, by believing they had some kind of talent. And, they kept trying. It's brutal advice, but it's true. I was incredibly lucky that my first novel was accepted. Ken Follett wrote twelve novels before The Eye of the Needle was accepted for publication. J.K. Rowling had to hawk her first novel around and around. Nobody wanted to know about a little boy with a wand.

Is there another novel coming?

I'm afraid not. I'm an old codger, and best off sitting in the garden and playing with the grandchildren. Of course, I said the same thing two novels ago, but I think the memoir is my last writing project.

Congratulations on writing The Outsider, an absolutely riveting memoir filled with intrigue, and every bit as exciting as your novels.

Mark Rubinstein's latest novel is The Lovers' Tango.