For over a decade, I have regularly attended the annual Sheep and Wool Festival in Rhinebeck, New York, a celebration of all things sheep. Scores of stalls sell hand-crafted woolen sweaters, photographs of sheep, spindles, spinning wheels, fleece, books about sheep and so on. The sheep, of many breeds, are present as well, and they are obviously raised with a great deal of care and affection. Visitors constantly admire them, touch samples of their wool, talk gently to them and ask questions about them. A few sheep appear to bask in the attention, and most appear indifferent to it, but all appear at least content.

Several stalls offer lamb and mutton; loving sheep and eating them have, for millennia, gone together with surprisingly little tension. It is hard to imagine a festival in which the love of pigs and the taste of pork are celebrated in such comfortable proximity. But relationships that we lump together under the heading of "domestication" do not follow any single pattern or prototype. The bond with humanity is profoundly different for dogs, pigs, bees, sheep and other animals. Each relation entails unique values, duties, uses, problems, symbols and mythologies. This celebration in Rhinebeck will seem less paradoxical if we consider the entire history of human relations with the ovine tribe.

Scholars believe the sheep was probably the second animal after the dog to be "domesticated," a bit before its relative the goat. The human bond with sheep rivals that with dogs in both historic importance and intimacy. Human, dog and sheep eventually formed a complex relationship, the foundation of what we now know as "civilization." People cleared the land for sheep and protected them, receiving in return their milk, fleece and meat. Dogs guarded the sheep, and obtained in return a share of their meat from human beings. Sheep of that era shed their fleece naturally and did not need to be sheered. They did eventually give their lives, but their life-expectancy was not necessarily reduced from what it had been in the wild. Until the end, sheep could count on plenty of pasture, safety from wild carnivores and shelter from the elements. All parties could enjoy one another's company, but, at least in pragmatic terms, the sheep certainly got the best deal of the three.

We traditionally have thought of these relationships anthropocentrically as two successive domestications, in which man first subjugated canids, which then aided him in dominating the sheep. But in many ways, this triad seems to center mostly on the ovine partner. Sheep demanded the most exertion from the two companion species, and also obtained the most obvious benefits from the arrangement. Furthermore, the triad involved profound changes in the relationship between canine and sheep, which human beings could not easily control. The dogs had to conquer their instinct to attack the sheep, and these hounds even turned against their relatives, the wolves. A ram can be fully a match for a dog or wolf, but rams also had to restrain any impulse to attack. At least initially, the triad was a complex symbiosis, involving three species and at least that many distinct bonds. Perhaps it anticipated the class-based structure of later human societies, with a division into priests (sheep), warriors (dogs) and tradesmen (human beings),

In historic terms, the pasturing of sheep has been a mixed blessing. On the positive side, it maintains the soil far better than agriculture, and supports a much greater diversity of plant life. Nevertheless, overgrazing eventually turned most of Greece into a semi-desert, led to the erosion of soil on mountainsides in Spain. In early modern times, communal fields in the British Isles were consolidated under private ownership, in order to provide pasture for sheep, forcing many families into poverty. I suspect that some of that may have been done neither for humankind nor for the environment, but rather for the sake of sheep, probably "man's best friend" after the dog. As Roger A. Caras has written in A Perfect Harmony, for shepherds, "... the well-being of the flock is all; everything else falls by the wayside."

Civilization may have begun with a three-way partnership of equals, but a lot has changed since then. Several other animals have been added to the club, including the bee, goat, pig, cat, chicken, carp, cow and silkworm. Every one of these has increased the complexity of the relationships, adding new duties, tasks, and customs. Humankind has become increasingly central, while other creatures have, at least from our perspective, been marginalized. Dogs, however, now share not only the homes of people, but almost every amenity or problem that comes with human status, everything from canine television shows to psychiatrists. Sheep continue to have special importance, and the Industrial Revolution may arguably have begun with new techniques for breeding them. In 1996, Dolly the sheep became the first animal to be successfully cloned. The bond between dog and sheep has largely been obscured, though it survives in a few rural areas. But, today, people as well often feel marginalized by their own technologies, and fear that computers may usurp our presumed supremacy.

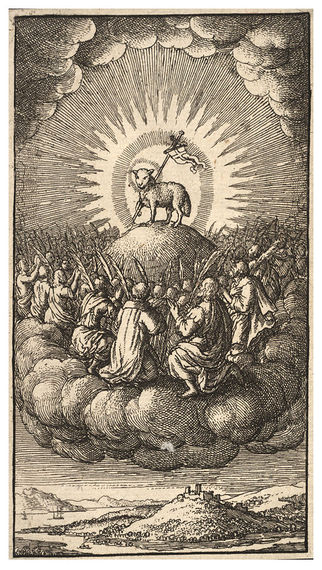

Nostalgia for the primordial bonds uniting man, dog and sheep has long pervaded human culture. Biblical metaphors for the relation of people to God or to their leaders are taken mostly from sheep and the pastoral vocation. Most of the Patriarchs including Abraham, Moses, Jacob, and David were shepherds. Psalm 23 begins, in the King James translation, "The Lord is my shepherd/I shall not want..." Bishops still carry a ceremonial shepherd's staff, a crosier, and a congregation is called a "flock." Jesus has often been depicted in the form of a lamb, adored by patriarchs, kings and saints.

Idealization of the pastoral life runs through Greco-Roman, as well as Judeo-Christian, culture, a tradition beginning with Hesiod in Theogony, when the Muses appear to him as he tends sheep on the slopes of Mount Helicon. It's most definitive expression is in Virgil's Georgics, and it may also be found in the work of many poets from the Renaissance. At the end of Cervantes' Don Quixote, the hero, weary of violence, dreams of becoming a shepherd. In Asia as well, the herding of sheep or goats is traditionally a vocation for those who long for solitude, often taken up by sages who retire from public life.

That brings us to the occasion of this article -- the beginning of the Year of the Ram. The placement of the ram in the Chinese zodiac reflects not only the cooperative disposition of domestic sheep, but also the agility, balance and sagacity of wild ones. Older sheep are known for their ability to find mountain paths through the most forbidding terrain, rather like a wise elder who can mentor his juniors through difficult times. We need that sort of wisdom desperately today, and that is one reason why the ram will take its place alongside the exuberantly dancing dragons, unicorns and lions at the celebration of the Chinese New Year. The ram had to be pretty special to start a new phase of global history by domesticating both dog and man.

_____

Selected Bibliography:

Budiansky, Stephen. The Covenant of the Wild: Why Animals Chose Domestication. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. Print.

Carras, Roger A. A Perfect Harmony: The Intertwining Lives of Animals and Humans Throughout History. New York: Simon & Schuster 1996. Print.

Clutton-Brock, Juliet. Animals as Domesticates: A World View through History. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2012. Print.

Sax, Boria. The Mythical Zoo: Animals in Myth, Legend and Literature. 2 ed. New York and London: Duckworth/Overlook, 2013. Print.

Sun, Ruth Q. The Asian Animal Zodiac. Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 1974. Print.