The idea for this blog came to me early one morning as I walked my dog. Suddenly our route was blocked by a cadre of people. Clad in white, long-sleeved, loose-fitting jerseys, they marched in an unbroken line in front of us. At strategic intervals a row of three marchers supported a pole on which they waved a large tricolor flag. The marchers' eyes were fixed straight ahead, oblivious to would-be passersby.

Envisioning a long delay before the procession ended, I inadvertently uttered a profanity. Jolted by the spontaneity and intensity of my negative reaction, I recognized the workings of my "reptilian" brain, a term I remembered from my studies of neuropathology years ago.

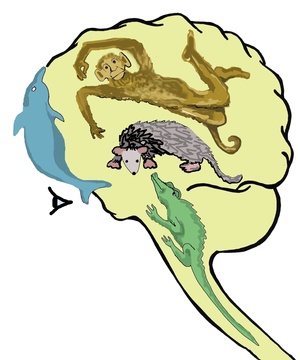

In the 1960s Dr. Paul McLean, a neuroscientist/physician, conceived of the human brain as divided into three basic parts based on their development, from simple to complex. Although the division is now considered to be an oversimplification, the terminology helps to understand how our brains function to negotiate the complicated tasks of living.

The "lower" portion of our brain resembles that found in crocodiles and snakes. Its major function is survival, which explains (the power and passion of) the animal's attack against those it perceives as invading its turf.

My reptilian brain perceived the marchers as invaders of "my" territory. Another example of a drastic response to a phenomenon that, in retrospect, seems trivial is road rage.

The reptilian brain operates on the premise of dominate or be dominated. Other traits include an inability to learn from mistakes, control over autonomic bodily functions, like heart beat, respiration, body temperature, mating, and sleep. In humans, qualities like rigidity, obsessiveness, compulsiveness, worship, fear, submission, and greed are attributed to this older portion of the brain.

The new brain, or more highly evolved neo-cortex, confers the ability to develop language, to reason, to become self aware, to correct our mistakes, and most important, to take charge of our reptilian brain.

The reptilian portion of my brain caused me to react angrily to what I perceived as "invasion," but my neocortex stepped in to remind me that others have a right to be here too.

Distinguishing the functioning of our reptilian brain from the neocortex can go a long way to helping us bring peace and prosperity to our planet. It is our great neocortex that confers our humanity and separates us from all other animals.

(Located in between the reptilian brain and the neocortex, the limbic system, seat of our feelings and emotions, mediates the responses between these other two. This middle brain or emotional center deserves a blog of its own, so I won't address it here.)

Arthur Clarke (1917) (books by this author) a great science fiction writer, author of 2001: A Space Odyssey, held out high hope for humanity. He said in a message delivered in 2007 on his 90th birthday, "I have great faith in optimism as a guiding principle, if only because it offers us the opportunity of creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. So I hope we've learnt something from the most barbaric century in history -- the 20th. I would like to see us overcome our tribal divisions and begin to think and act as if we were one family. That would be real globalization..."

Conclusion: To accomplish Clark's hopeful vision, we best recognize the workings and our ability to control our reptilian brain. Our superior neocortex grants us the capacity to be magnificent creatures capable of supporting civilization and the well-being of our planet (as we recently witnessed in the international climate control meetings in Paris). Here's to a less violent 2016 and a more civilized century!