We started Zidisha in 2009 as an alternative to microlending platforms like Kiva, which partner with local microfinance organizations ("field partners") to liaise with borrowers on lenders' behalf. The locally managed lending programs funded by Kiva and similar microlending websites are probably the best way to serve borrowers who do not use the internet. But there's a huge drawback to this arrangement: the field partners must charge the borrowers steep interest rates to cover their operating costs. In microlending, interest rates of 40% or more are common, and even Kiva borrowers pay average interest rates of 35% for loans made by lenders at zero interest.

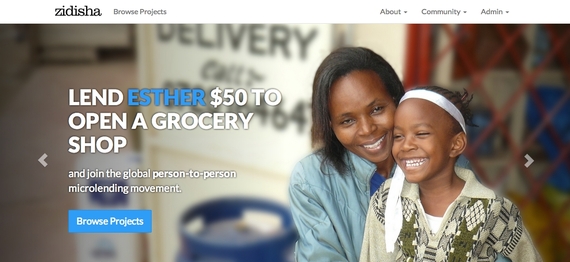

With more and more people coming online in developing countries, we saw an opportunity to use an internet-based approach to make microloans affordable. We did this by eliminating the intermediary microfinance bank altogether, instead using a person-to-person lending platform to connect individual borrowers directly with individual lenders. Through the use of technology and iterating a lot on our model, we've been able to get the per-loan cost to the borrower down to just 5%. The following is the story of how we did that.

Evolution

By 2009 advances in payment transfers and internet connectivity had made direct P2P microlending technically possible, but most microfinance practitioners assumed that low-income people in developing countries would not repay loans responsibly without the supervision of local branch offices, loan officers, and other expensive infrastructure. The idea of inviting lenders in wealthy countries to send a $100 loan over the internet to a penniless youth in a Nairobi slum, without any local staff to enforce repayment, seemed absurd.

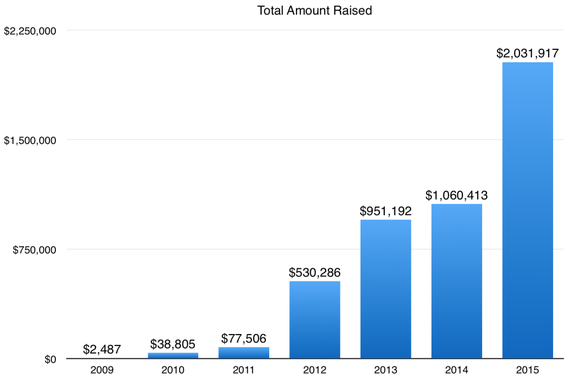

And little about Zidisha in our early days seemed to predict success as a tech startup. I wasn't technical at all: at the time other future startup founders were hacking, I was riding motorbike taxis around Africa and hanging out with villagers under Baobab trees. I couldn't program and had no cofounder. I married shortly after founding Zidisha, and launched the organization from the one-room apartment my husband and I were sharing with my old grad school roommate. Despite dozens of grant applications, we raised no outside funding for the first three years, so I kept my day job and worked on Zidisha on evenings and weekends. Growth was slow for a long time.

Our first lucky break came at the end of 2013, when Zidisha became one of the first nonprofits to be accepted into Y Combinator. My husband couldn't leave his work as head of a martial arts school, so our two-year-old son Adam and I relocated to Silicon Valley for three months to do YC by ourselves. I took the plunge and learned to program, though not without mishap: one of Adam's first sentences was "The website is crashing!" which he learned from my repeated emergency calls to our web hosting service.

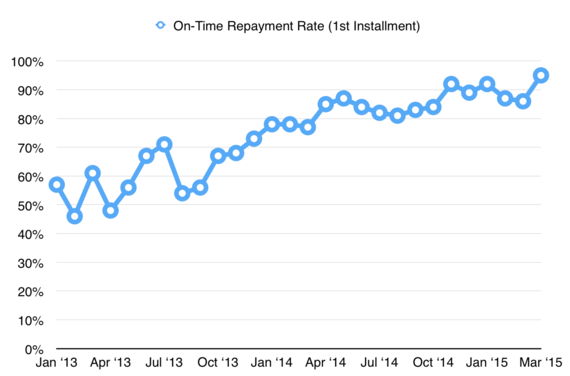

Thanks largely to Y Combinator, growth took off. Over the past six years we've facilitated over $5 million worth of loans between 50,000 people worldwide. And it turns out that developing country entrepreneurs, despite their hardship, do repay person-to-person loans at impressive rates: About 80% of Zidisha loans made in the last year are repaid or repaying on time, with those in arrears refundable to lenders from reserve deposits made by borrowers. We've demonstrated that a radically low-cost, direct online microfinance platform is viable over the long term and at scale.

Getting to this point has required substantial evolution of our lending model. Over the years, we've become less like a traditional microfinance program, and more like a decentralized online community. Zidisha today probably has more in common with eBay than with the Grameen Bank. Nevertheless, it's our hope that some of our frugal innovations can prove useful for reducing microfinance costs beyond Zidisha. In particular, our unusual approaches to recruiting and vetting new borrowers, front-loading borrowing costs, borrower-driven repayment plans, and decentralizing mentoring services to our members can be applied with little adaptation at traditional microlending organizations.

An invite bonus system to incentivize recruitment of trustworthy borrowers

At the beginning, it was hard to persuade anyone to apply for a loan, despite the vast cost advantage over local lenders. Online marketplaces were a foreign idea in developing countries, and the low cost just made us sound too good to be true, like a scam. People didn't see how a service without physical offices and employees could provide loans. (In some cases, early Zidisha adopters were accused of witchcraft when they showed up with lump sums of cash in places a loan officer hadn't visited in months.) It was thanks to the work of early Ambassador volunteers - like Mien De Graeve, who left a comfortable life in Belgium to evangelize Zidisha in the villages of Burkina Faso - that we achieved the critical mass of borrowers necessary for word-of-mouth growth to take off.

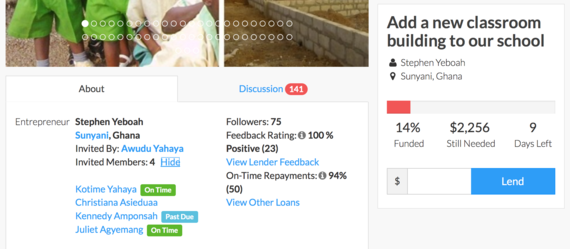

Today, the vast majority of borrowers learn about Zidisha from acquaintances who have already received loans. In 2013 we added a tool for borrowers to invite new members via email, and this allowed us to measure the referral flows more easily. Our members often tell us they are careful to recruit only people they know are trustworthy, and it indeed turned out that borrowers who had been invited via the email tool had substantially better repayment performance.

In 2014, we began offering a $50 increase in the starting credit limit to applicants who had been invited. We also limited the privilege to send invites to borrowers who 1) had good on-time repayment records, and 2) had not invited borrowers with poor repayment performance. Each eligible borrower could send up to three invites at a time. When an invitee began repaying their loan, if the inviter remained eligible, space would open up to send a new invite.

Over time, this led to a system where only networks of trustworthy borrowers grow and spread, driving ever-better aggregate repayment performance. Today, 53% of borrowers join using the invite bonus tool.

Tiny first loans as a vetting mechanism for new borrowers

Our vetting process was originally very cumbersome. In an attempt to mimic local banks, we would ask applicants to scan in various legal documents - in places where scanners were scarce and few knew how to use them - and our volunteer team would use Skype to call applicants and references on their cell phones to verify information. This worked poorly: it could not scale beyond a few thousand borrowers, and fraudsters anyway figured out how to game the system.

Soon after our launch, one particularly enterprising crook in Kenya colluded with an M-Pesa mobile payment agent to open a series of false payment accounts matched to sock-puppet Zidisha borrower accounts. He ended up stealing a couple thousand dollars' worth of loan disbursements - a fortune for our organization at the time - before going into hiding among the Masai nomads. At the time I still had a day job, and I would get up early each day to call the local police chief before work and make sure that local law enforcement was still pursuing the case. Finally, the alleged thief was arrested. Then he was suddenly released without trial. We were told that he had bribed the judge - something that we at Zidisha refused to do. We never did recover the stolen money.

Later, we tried contracting with local credit reference bureaux and NGOs to vet applicants. That was even worse: turnaround was slow and the local agents required extensive oversight to ensure they were conducting the checks properly and not engaging in corruption.

We've since developed more sophisticated automated vetting measures, including machine learning algorithms to detect patterns that we've learned predict fraud risk. But one of our most important risk mitigation measures is based on a simple observation: dishonest applicants rarely wait out the system in order to qualify for a large loan. Instead, they are likely to disappear immediately with whatever amount they are first given.

Based on this insight, we gradually did away with the cumbersome paper-based vetting process (though we continued to develop our website's automated vetting system). Instead, we limited the net amount of cash first-time borrowers receive to about $20 on average, effectively screening out dishonest applicants before they are entrusted with substantial amounts. The average vetting cost of a new Zidisha member is equal to the percentage of that $20 average which defaults.

We also observed that the more we reduced the starting loan amount, the more fraud attempts decreased. Presumably, the reward for gaming the application process had become insignificant enough that the fraudsters no longer bothered.

Using small first loans as tests for credit-worthiness allowed us to safely transition to a mostly automated vetting process, while continuing to improve repayment performance.

Front-loading borrowing costs

At first, inspired by eBay, we allowed borrowers to offer interest to lenders at rates of their own choosing. Lenders would then compete in a reverse auction, in which bids with the lowest interest rates would be retained to fund the loan. This worked poorly: borrowers had no idea what rates to propose, and lenders had little desire to mix competition with charity. So in 2014, we took the interest rate decision away from borrowers and gave it to lenders (with a maximum cap of 15%).

In early 2015, we examined the data we had gathered since lenders began setting the interest rates in an attempt to identify the relationship between interest rates and the financial sustainability of lenders' funds. We expected that the funds of lenders who charged high interest rates would gain the most value over time. But it turned out that the opposite was true: Higher interest rates were so closely correlated with higher default rates that charging more interest caused lenders to lose money, and the lenders who opted to fund loans at zero or almost-zero interest had the highest repayment rates and best financial sustainability over time. (This was not because lenders were assigning higher interest rates to applicants who looked risky: lenders almost always applied the same rate to all borrowers they funded.)

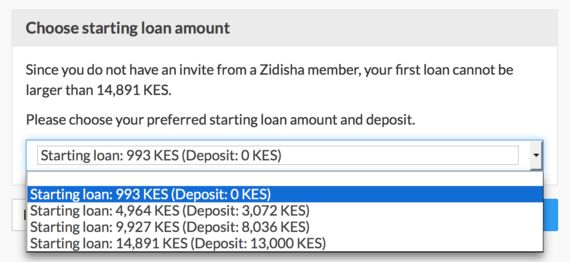

Based on this learning, we adopted a new approach: all loans would be interest-free. Instead, we would ask first-time borrowers to make a deposit into a reserve fund that reimburses lenders in the event of default. However, instead of asking borrowers to deposit gradually increasing amounts to offset increasing loan sizes over time, we took the unusual approach of asking for the entire deposit up front.

This resulted in very unattractive terms for the first loan: The deposit would be more than half of the loan amount - well above the cost charged by local banks for a loan of the same amount. But after repaying the first Zidisha loan, borrowers would enjoy access to unlimited successive loans of increasing amounts, at zero interest and with no additional deposit required. The intent was to appeal only to applicants who knew they would repay the first loan responsibly and qualify to benefit from our platform over the long term.

This approach has improved financial performance, in that deposits have been enough to offset expected defaults. But it raised concerns that it would shift our applicant pool to more affluent borrowers who could more easily afford to pay the initial deposit. To prevent this, in late 2015 we introduced the option to start with a very small loan - $20 if invited, otherwise $10 - with no deposit required at all. Applicants who preferred to pay a deposit could choose from a selection of larger starting loans (up to $150) with deposit requirements increasing in line with the starting loan amount.

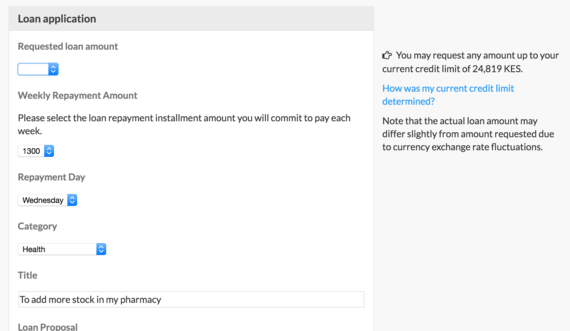

Self-directed repayment plans

Balancing repayment discipline with accommodation for disruptions in borrowers' ability to pay is a perennial struggle for microlending services. Most Zidisha borrowers are self-employed, with erratic cash flows, and lack insurance or substantial savings. They live in places where serious illness and accidents are common, theft of assets is rampant and government safety nets few to nonexistent. Under such circumstances, it is not realistic to expect repayments to follow a predetermined schedule all of the time. We also don't believe it's ethical to force low-income people to choose between repaying a loan and putting food on the table. But making repayment expectations too flexible rewards free riders, who when left unchecked can destroy lending programs.

At Zidisha, borrowers choose their own weekly repayment amounts, and the day of the week on which repayments will fall due, at the time they apply for a loan. This helps ensure repayment schedules fit the applicant's current cash flow, but does not allow for the inevitable fluctuations in cash flow during the course of the loan.

At first, we tried to solve this problem by offering borrowers in financial hardship the option of deferring scheduled repayment installments for a limited time. This sounded reasonable, but worked poorly in practice: once repayments began to be skipped, it was very hard to get them to resume.

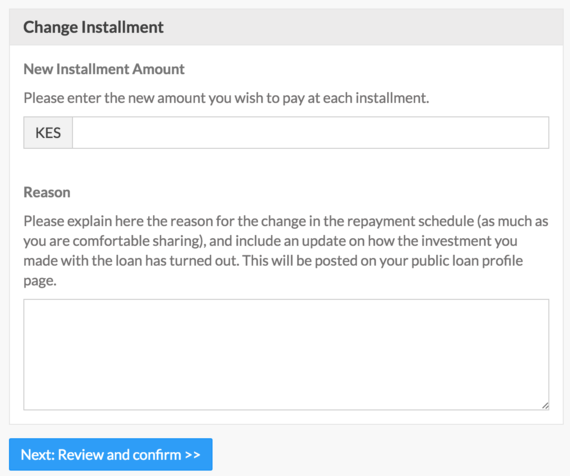

Today, borrowers can no longer skip or defer scheduled repayments without penalty to their on-time repayment score and credit limit. However, borrowers who cannot afford to pay the scheduled installment may log into their accounts and change the installment amount to whatever they wish, even as little as a few cents if desired. As long as that adjusted amount continues to be paid on time and in full each week, the borrower preserves their good repayment score. Once cash flow improves, the borrower may adjust repayment amounts upwards again.

A good example is Grace Dawo, a widowed mother in Kenya who used a series of Zidisha loans to start a peanut butter business in her home. During her second loan, a pinched nerve left Grace saddled with hospital bills and unable to work for over a month. She adjusted her installment to a tiny token amount and continued to deposit it faithfully each week until her health and finances recovered. She then repaid the loan in full and went on to raise another, which she used for better packaging and the government certification needed to supply her peanut butter to local supermarkets. Today, Grace's daughter Rosemarie is attending a quality private school thanks to profits from the peanut butter business.

Financially, it makes little difference whether someone repays a few cents or skips the installment entirely. Psychologically, the difference is immense: the act of sending the installment reinforces the habit of repaying and one's self-image as a responsible participant in the Zidisha community. And since there is no minimum installment amount, continuing to make weekly payments need not interfere with other financial needs.

One might expect that such flexibility would incentivize borrowers to repay as little as possible each week. In fact, we've observed the opposite to be true: borrowers tend to repay loans as quickly as they can, in order to access new loans to further grow their businesses. We had to institute minimum loan holding periods between credit limit increases to prevent people from graduating to large loan amounts too quickly.

Borrowers as volunteer mentors

Prospective applicants are often more comfortable learning from other people than by reading things online. One of the most common requests in Zidisha's early days was for a local office borrowers could go to with questions. Though our website provides extensive information, and our volunteer staff answer questions via email and SMS in local languages, new members often need a local person who has borrowed with Zidisha to explain the process before they feel confident enough to use it.

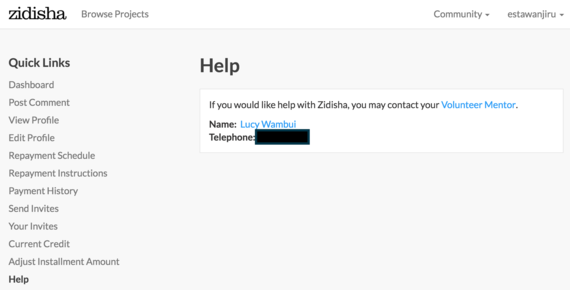

We observed early on that a large minority of experienced borrowers were very active in helping new members to join and participate successfully in the community. In 2013, we began officially recognizing these leaders as "Volunteer Mentors" and allowing new members to assign themselves to a Volunteer Mentor in their geographic area. Mentors' phone numbers are then displayed in the new member's dashboard with an invitation to contact them with questions. Mentors likewise may telephone mentees, and are requested to check in with them by phone and advise them on the option to adjust the installment amount if loans go into arrears.

Decentralizing these interactions to borrowers poses a risk as well as an opportunity. Zidisha has always struggled with scams by individuals who present themselves as Zidisha agents and promise loans in return for kickbacks. To protect the Volunteer Mentor position from similar fraud, we were careful not to give mentors the power to make admittance decisions for applicants. We also don't give Volunteer Mentors any compensation, or even reimburse costs they incur in their volunteering. This helps ensure that the Volunteer Mentor role only attracts people who are motivated by the desire to give back to the community - of which there are many at Zidisha.

The story of Sammy Kanja illustrates the community-spiritedness we often see among Volunteer Mentors. One of our founding members in Kenya, Sammy used Zidisha loans to acquire donkey carts for transporting farm produce to market, and a dairy cow whose milk sales supplied his family with a daily stream of cash. Sammy was Volunteer Mentor for a neighbor, Francis Kiiru, with whom we lost contact suddenly in late 2013. He eventually discovered Francis in a Nairobi hospital, severely wounded in the Westgate Mall terrorist shootings, and with no means to pay the hospital bill. Sammy and his wife decided to sell the donkey carts and dairy cow which had been the source of their family's financial well-being, in order to pay for Francis's treatment. When lenders heard Sammy's story, they raised donations to help him buy a new dairy cow. Sammy, now on his fifth loan, remains an active Volunteer Mentor today. He has helped dozens of members in Kenya learn to participate successfully in Zidisha, and these in turn are mentoring other new members - the network effect at its best.