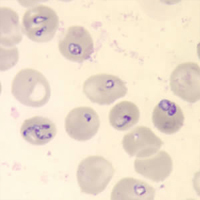

Babesia parasites in red blood cells. (Source: CDC)

While we lived together, a good friend of mine who hails from West Africa taught me to think beyond geopolitical borders. Among countless stories, she sometimes mentioned exotic illnesses that were common in other parts of the world. One is malaria -- that infamous mosquito-transmitted parasite that causes severe flulike symptoms most notably characterized by a sudden fever that comes and goes every couple of days. Those who are treated for the sometime-fatal illness may experience recurrences because the pathogen sometimes is not treated effectively or fully and can come back years after the initial infection. My friend had had malaria several times. "It's the best way to lose weight," she joked. She told me about other parasites, including guinea worms, which enter the body through water and exit, rear end first, by forming blisters and then breaking through the lower extremities.

I couldn't believe that parasites are still common anywhere in the modern world -- parasites! Learning this made me glad to be American -- we know that our pets can get heartworm, but the United States has proper sanitation and we are too hygienic to worry about such things, right? Such bravado often yields difficult lessons.

For my part, over my lifetime I've had fevers many times and have become accustomed to being a sponge for other people's seasonal illnesses. If someone in my office or classroom sneezed, I was going to be next; that's just how my life went. And in my early 20s for a few years I kept getting recurring pinkeye, inexplicably, and as a gay man that made me paranoid about HIV. I knew that conjunctivitis is an opportunistic disease that most adults don't get often unless they have compromised immune systems. I tested myself for HIV every few months and because of the weird pinkeye recurrences and the night sweats I started having, I always expected my next HIV test to come back positive -- even though I never did anything to put myself at high risk.

Everyone thought I was paranoid. Yet weird health issues continued throughout my 20s and into my 30s; for a couple of years, I had trouble catching my breath and having grown up in a house thick with cigarette smoke I wondered if it was possible I could be developing emphysema. It was that bad. My doctor laughed at the idea and -- without even checking my breathing with a stethoscope -- she prescribed Zoloft and said once I get my anxiety under control, my breathing will improve.

Nevertheless, one thing I knew I was safe from in the U.S. was parasites -- parasites! You have to be living in a rainforest or alongside the Nile to get those, right? So wrong.

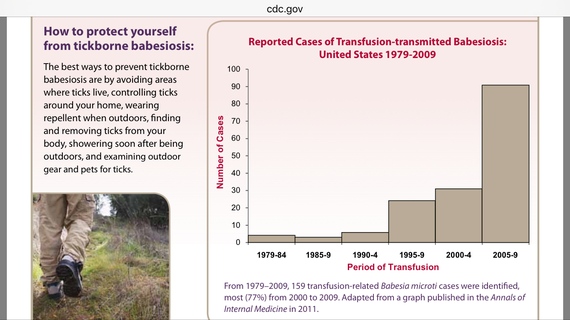

The red blood cell parasite Babesia is transmitted increasingly in the United States through blood transfusions, yet unlike with HIV, donated blood is never tested for Babesia. [Source: CDC]

Recurring pinkeye, night sweats, "air hunger" as it is known (this fitting description would have been useful in my 20s) and a number of other unusual health complications are typical symptoms of babesia, a malaria-like parasite that is endemic to the northeast United States. Babesia is transmitted by the same ticks that transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that is associated with the term Lyme disease; however, it occurs so commonly in tandem with babesia, another pathogen called bartonella, and several other infectious agents that many now consider "Lyme disease" to refer to a multi-organism, multi-systemic infection that frequently involves Borrelia, Babesia, Bartonella and other tick-carried organisms that live and work in collaboration with one another to evade the human immune system.

Regardless, Babesia is indeed a parasite that invades human red blood cells and which manifests similarly to malaria. I've been diagnosed with Lyme -- Borrelia burgdorferi, but also two other commonly occurring coinfections, Bartonella and Babesia. While all of these pathogens are still somewhat confounding to medical science, Babesia is a close enough analog to malaria that it can be fairly well understood. It's also been identified as a burgeoning public health risk because of its potential for causing fatalities and the ease by which it can be transmitted via blood transfusion.

Babesia's similarities to malaria aren't only symptomatic; babesiosis treatment requires the use of antimalarial drugs, and like malaria, it can reoccur years after seemingly effective treatment, as Babesia reside inside of human red blood cells.

Babesia in Blood Banks

Babesia is becoming a significant public health problem in the United States. Like Lyme disease, which was first identified in the Northeast U.S. (It was named after its place of discovery, Old Lyme, Connecticut.) Babesia was first reported in Nantucket, Mass. in 1969. Like Lyme, babesia has spread from its point of origin throughout the U.S. to become the most common piroplasm-type (pear shaped) parasite that infects human beings. And like Lyme, Babesia isn't always easy to detect in human blood, particularly among asymptomatic patients.

Unlike Lyme, though, it is commonly accepted that Babesia can be -- and is being -- transmitted not only by ticks but also through blood transfusions. According to this article, babesiosis has become "a major transfusion threat." Over 5 million blood transfusions take place annually in the U.S., and donated blood is never tested for babesia, which is easily transmitted via transfusion. According to the article, babesiosis is:

the most frequent transfusion-transmitted infection with approximately 162 cases reported since 1980 and 12 associated fatalities in the period 2005-2008. The major reason for this increase is that babesiosis can be asymptomatic, indeed clinically silent, in healthy adults who are the dominant blood donors.

This past August, a former first lady of New Jersey died from a recent babesiosis infection.

As of now, donated blood is screened for babesia only by asking donors if they have babesia. If they say no, then the blood may then be transfused to recipients. This is problematic not only because of the risk of donors not being forthcoming about their health, but also -- probably primarily -- because many people who carry babesia are asymptomatic and therefore can't disclose an illness they don't know they have. The FDA finally recommended last May that all donated blood should be tested for Babesia; however, at this time it is not, and while testing would be better than not, blood tests for Babesia -- like those for Lyme and Bartonella -- often result in false negatives, particularly among asymptomatic infected people.

The non-testing policy for babesia in donated blood is a stark contrast for the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) highly conservative HIV policy, which not only tests (as it should) all donated blood samples for the HIV virus, but which also prohibits blood donations from any man who has had sex with another man within the past 12 months (yet has no similar prohibition against heterosexual men and women, regardless of the number of sex partners or whether those partners engaged in high-risk sexual activities).

[Transfusion-transmitted Babesia] TTB has become one of the most commonly reported transfusion-transmitted infections in the United States. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop sensitive and specific methods for screening for this pathogen or alternative methods for eliminating it from the blood supply.

A July 18, 2014 memo from American Association of Blood Banks President Dr. Graham Sher to AABB members cautioned that "TTB is the leading infectious cause of mortality (38%) in transfusion recipients as reported to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)." The memo also notes that "of all the total cases reported, 77 percent were reported from 1999 to 2009, suggesting a rapid increase in frequency..." The memo encourages better screening for babesia, but observes that "no FDA-licensed testing method to reduce TTB incidence is available."

Recently, the Rhode Island Blood Center laid off 60 employees to cover the cost of screening blood for Babesia because of the prevalence of babesiosis in the New England region.